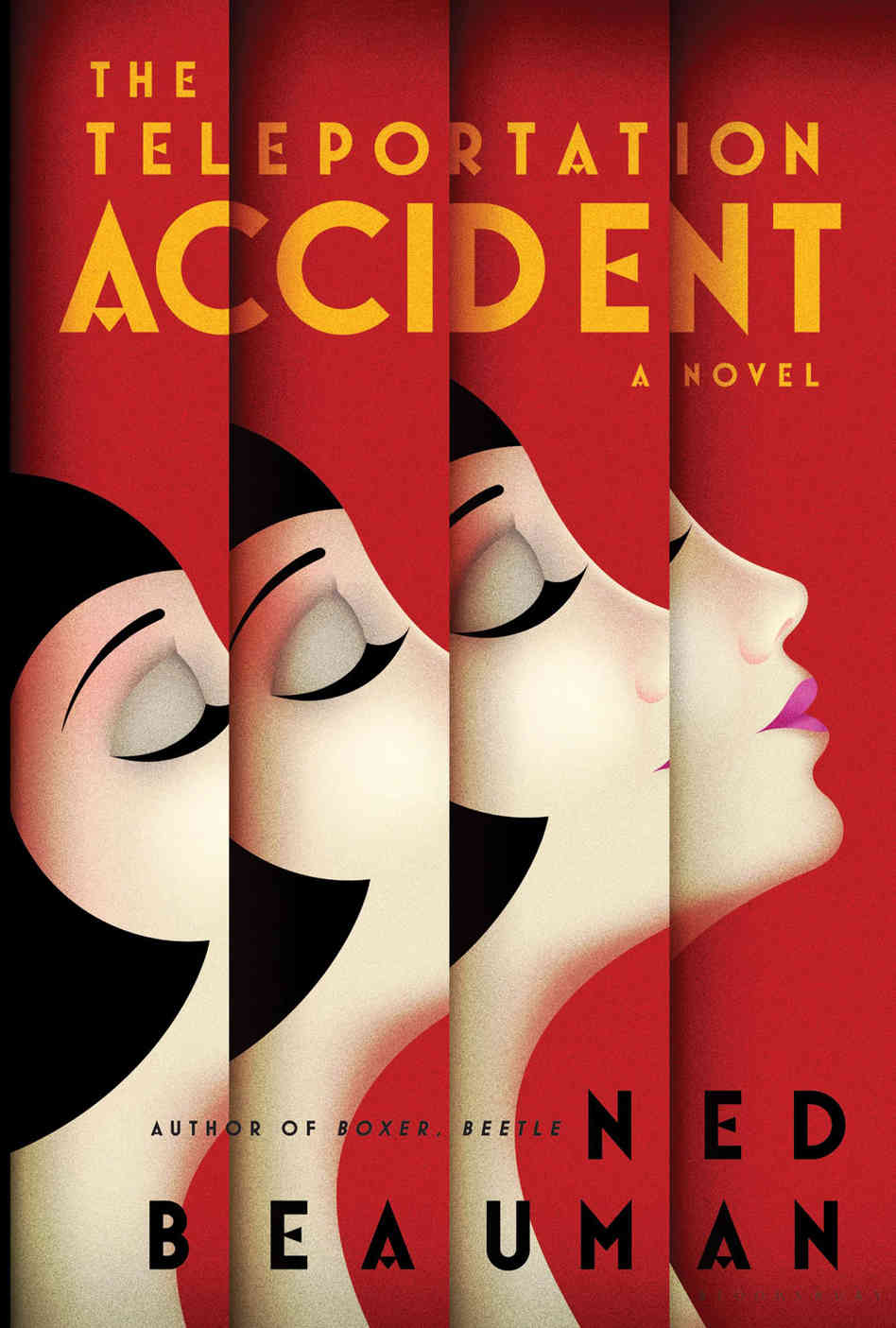

The Teleportation Accident by Ned Beauman

All the world’s a phase

In every capacity of life, we find markedly clear divisions between art and science. For example, an advisor will attempt to steer an academic career in accordance to strengths in one of two degree-producing fields. One or the other will be designated on that final sheet of pedantic paper…but very rarely both.

Studies show the ability to absorb information directly correlates to having a creatively centered right brain or a more analytical left. One hemisphere sees pictures, diagrams, visual representations and symbolism befitting an art film. The other processes numbers, graphs, logical parameters and formula-driven problem-solving.

Societal boundaries can be every bit as monolithic. Author Ned Beauman makes this allusion in his 1930s-and-onward Teleportation Accident, but the author paints here a much different picture through protagonist Egon Loeser, an almost painfully artistic archetype making a living as a Berlin-based theater set designer.

Loeser makes a point to go “out of his way not to socialize with people with real careers.” He considers them “impossible to talk to.” Yet even though this starving artist’s hobbies, interests and livelihood may be pigeonholed, Beauman makes it his point to obscure the lines between an art/science union as much as possible.

“If Loeser could ever get his Teleportation Device working, then in future productions it might sling actors not just through space but through time.”

Loeser’s passion lies in a Teleportation Device invented centuries before, in the 1600s, by luminary set designer Adriano Lavicini. (The Teleportation Device manipulates and moves props, backdrops and actors during a play to change a scene as quickly as possible.) It’s only when Loeser meets Professor Franklin Bailey at the tail end of this novel that he gains a more scientific perspective, this through the professor’s own similarly (and aptly) named Teleportation Device. The more modern device successfully transports a physical object from place to place. The working theory Bailey provides for his creation? Simple…and intentionally vague. To send an object to another place, you must exchange it with an equal amount of physical representation from its intended destination.

Throughout The Teleportation Accident, Loeser treks the globe. He occupies a new social stratum in each new location, once working a respected theater in Berlin, next keeping the barrel-scraping company of confidence men in Paris, then holding a place as a revered—and manipulated—socialite in Los Angeles. Loeser’s tumultuous travels differ little from the effects of both Teleportation Devices, new and old: rapid-fire scenery changes take place with multiple moving pieces and personalities. These exchange old sensibilities for new, previous supporting casts and physical surroundings for more recent.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-