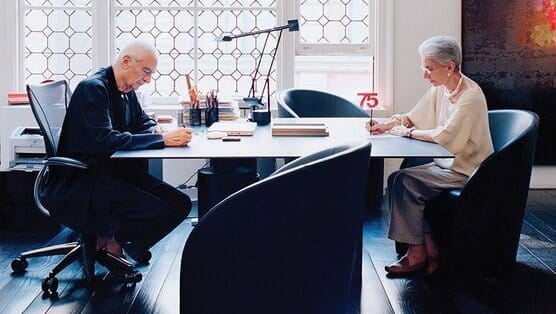

Two Lives, One Vision by Jan Conradi

Design.

It is everywhere, all around us, the most omnipresent component of the zeitgeist, the silent art, hidden in its ubiquity, immeasurable in its importance. Those possessing the right eyes hail Design with the same fervor as painting, sculpture, poetry. Aided by its permeation of life, Design holds a distinction as the art most likely to be confused—or conflated—with the Holy Spirit.

You’ll hardly be surprised to learn that Design touched every aspect of this review: the chair and desk, the laptop, the layout of the word processor, the layout of its final appearance in Paste and, of course, the book itself. Any sign you have trusted and followed, any couch or bed or countertop or washing machine you have fucked upon, any magazine or book you have read … Design got there first. The fixtures that light your home, the modes of transportation that move you through the milieu, the monument that will mark your grave: all designed. The only possible escape would be to throw one’s self, naked, into the surf, shaking off the shore until you saw nothing but sea and sky and cephalopod. (Even then Design would not be absent, merely lying fathoms below, sunken and full of ghosts.)

Ubiquity breeds either worship or indifference. In our time, Design worship holds sway. Was not one of our most critically hailed albums of the young decade, Kanye West’s Yeezus, inspired primarily by a Le Corbusier lamp? The halls of the Driehaus Museum blossom and bud, its voluptuous curves and shimmering nacre lit by the prismatic hues of Louis Comfort Tiffany. The Internet provides to many millions of surfers many millions of finely designed websites (and many millions more heretical abominations).

Even picking out one’s Tumblr theme invokes Design … touched upon, weighed, Design engaged in a way the general public never engaged with Design before. (For the record, my theme offers homage to Saul Bass, the famed graphic designer perhaps best remembered for movie credit sequences and corporate logos like United’s “tulip” and AT&T’s striated blue orb.) The great pendulum—and this would assuredly be a most beautiful pendulum, ebony pivots and rods with a brushed steel bob—swings toward worship and the Temple of Design, and no temple would ever look better, architecture being Design and all.

A temple needs deities. A temple needs scripture.

Massimo and Lella Vignelli, paragons of modernism, of the clean, resounding, simple and beautiful, may be as gods, according to Jan Conradi’s biography/gospel Lella and Massimo Vignelli: Two Lives, One Vision. Conradi, who also designed the book, is a professor of the form at Rowan University. The author met Massimo in 1987 while researching a graduate thesis.

The book is thick with the language of worship. The mission of Unimark, the seminal design firm the Vignellis helped found, existed, in Massimo’s view, to “spread the gospel of functional design.” Greg Smith, a designer in the Detroit office (a ‘60s anachronism; can you imagine a hip, influential firm opening offices in New York, Milan, Chicago and Detroit?), recalls Massimo as “the big hero; some referred to him as the ‘Design God.’”

The Vignelli role in Unimark, kept hermetically separate from the business side, may be summed up in Massimo’s dismissal of MBAs and Madison Avenue types as “the philistines talking about money in the temple of design.” Behold, the kinds of stances icons are meant to take, those that instill genuflecting remembrances in colleagues, friends and creative progeny.

And what icons! Vignellis lived in the sky (American Airlines), and in the ground (the MTA subway map-cum-modern art, darling), and in our hands (the Little Brown Bag). Their words became our words (the Vignelli aesthetic drove the predominance of the Helvetica type font). The designs happen to be—as the couple always maintained, and as Conradi’s book tautologically makes mention—timeless in their simplicity, extraordinarily beautiful, beautiful, in this century as they were the last, as they will be in the next, ad infinitum.

The Vignellis designed logos and identities and various other two-dimensional commissions that come to mind whenever one mentions “graphic design.” They also dreamed up furnishings and house wares and buildings and interiors. They were Designers, for god’s sake, designing sundry and all, creators on a deific scale.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-