Jason Lutes on His Monumental, Accidentally Prescient Berlin

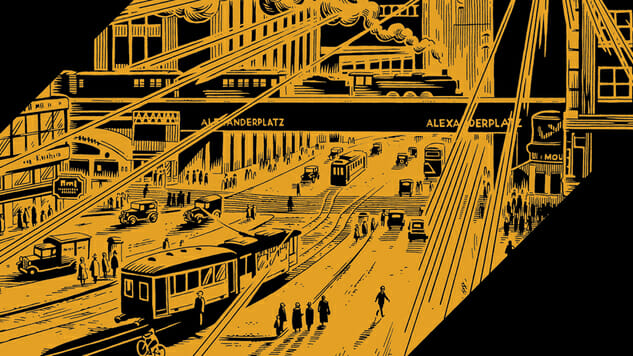

Art by Jason Lutes

You could definitely kill a palmetto bug with Jason Lutes’ Berlin, published in small chunks over the span of 22 years and now compiled into a single, gorgeous volume. But you have other books that would be more expendable. Before now you would have had to track down the individual thirds of the book or even tried to get to it 1/24th at a time, and although Lutes had good reasons for putting it out that way, it sure is satisfying to be able to read it all the way through, especially at our current dark moment. Lutes talked to us on the phone for half an hour recently, and we managed to cover quite a lot (mostly by talking fast). Here’s some insight into what it feels like to pursue such a large project over many years, to be “accidentally prescient” and to be finally done with the book.

![]()

Berlin Cover Art by Jason Lutes

Paste: Hi, Jason. I’ll do my best not to repeat too many of the questions you’ve been asked a million bazillion times, but some of them I’m going to have to ask because it’ll work better that way when it’s transcribed.

Lutes: That’s on me to try to come up with different answers!

Paste: Good luck! Why Berlin in particular?

Lutes: I chose it pretty much on instinct or almost a whim, I guess you might say. I didn’t know much about the time period or the place. I was living in Seattle, Washington, in 1996, and I had just finished Jar of Fools, which is my first book, and I felt like that had been a great learning experience. I had kind of educated myself about how comics work. I was thinking about what I was going to try to do next, and I knew I was going to do something long. And then I saw an ad in The Nation for this book of photographs of Weimar Germany. I read the ad copy for it that kind of colorfully described the city at the time, you know, like, technology and art and politics were all breaking new ground. Europe had come out of the tragedy of World War I and the world had changed in this irrevocable way because of that, and the future was kind of unwritten and wide open and all these forces were jockeying for position. That was all very inspiring, and I decided after I read that ad that that would be the subject of my next book. But I didn’t know much about Berlin or Germany in the 1920s and 1930s, beyond Cabaret. So it was a total impulse, and along with the impulse came the desire to do something long, and I decided that it was going to be 600 pages pretty much at random. That seemed like a good length to really tell an epic story.

Paste: Did you know how long it was going to take you to write and draw it?

Lutes: I looked at my rate of production for my previous book, for which I had done like a page a week (but I had had a day job while I was doing that). So I quit my day job and I decided to make a go of comics full time, and I calculated that I could finish it in 14 years [laughs]. Which in retrospect is really crazy to think that I did that when I was 26 years old.

Paste: You were like, “That’s a good idea!”

Lutes: Yeah. [Laughs] I can’t even… But now when I look back, I’m like, Did I really make that decision? But I remember crunching the numbers and saying, “Okay, it’ll take me 14 years…” And I wasn’t even thinking about like, “How am I going to make a living?” or anything like that. I was just like, this is how long the book’s going to take me if I can do 50 pages a year. And then, as time went on, it was hard to make a go of it as a starving artist. The individual chapters were coming out one at a time, and I was getting a little bit of money from them but not enough to actually make a living. And then I fell in love, had kids, had to figure out how to support a family. So the kind of day jobs took over more and more hours in my week. So it ended up taking me eight more years than anticipated. [Laughs]

Paste: Does it feel good to stop?

Lutes: To be done? Oh yeah! I drew the last page the week before my 50th birthday. My adjusted deadline, when I looked at it, I was like, If I can finish this by the time I’m 50, that’ll be great. That’s a good deadline. So I increased my rate of production and managed to just get it done under the wire. That was in December and all my students were finishing up their first semester of final projects, and my wife and I had gotten married that year after being partners for 20-something years. In our little bubble here in Vermont, it was just this really wonderful period. People ask me, “Was there a void when you finished because you weren’t working on this big project anymore?” But it was the opposite. I felt light on my feet and completely, for the moment, kind of ignoring the problems of the larger world in my little pocket of existence here. It just put me in a really great state of mind, and I was super-excited to get to work on my next project because in all that time I was working on Berlin, I had many, many other ideas for stories I wanted to tell.

Paste: Are they going to be 600 pages long?

Lutes: [Laughs] Nope! No more epics for me.

Paste: I’m curious about your process. Did you write the whole thing first or did you write it one “episode” at a time?

Lutes: My work is very constraint-driven. I’ll set up limitations for myself and then try to improvise within that. So initially I had this page length and then I broke it down into 24 chapters of 24 pages each, so I had these little units. Within each 24-page chapter in comics, as you know, the page is a narrative unit in itself, and then within each page there are the panels. So there are these building blocks with which you can kind of break stuff down and you can use to figure out structure. It’s a great framework within which to work because it forces you to edit and it forces you to figure out what you want to do on a given page. I made some outlines and in the beginning I had some themes that I wanted to address, and I figured out who my main characters were. And, of course, it takes place in a real place in history, so I knew that there were some dramatic and social events that were going to appear. And then I put my main characters on a train and sent them into the city. The process of writing each chapter was an improvisational exercise. I had done two years of research, so I had all this stuff in my head about the city and what it might have been like. So my characters arrive in the city by train and then what happens after that is just a result of them interacting with people that they know and meeting new people and interacting with each other until they end up taking on a life of their own. I sort of followed them around to see what happened to them. So it was very improvisational but within a kind of loose overarching structure.

Paste: Did you know where it was going to end when you started?

Lutes: I knew that it was going to end when Hitler becomes chancellor, in 1933, but as I wrote the story, halfway through it I might have one notion about how the book would end for specific characters, what the final note would be for them, and then three-quarters of the way through the book that shifted and became some other notion. The ending as it now sits in the book, I didn’t really write that until I was probably about 100 pages from the end.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-