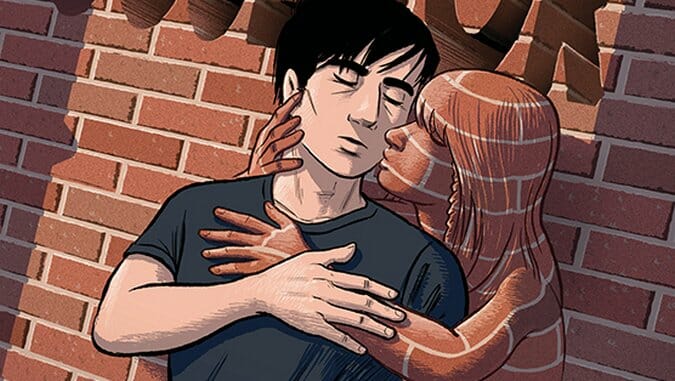

The Sculptor by Scott McCloud

Writer/Artist: Scott McCloud

Release Date: February 4, 2015

Publisher: First Second

Mild Spoilers

The Sculptor, like Frank Miller’s Holy Terror, Neal Adam’s Batman: Odyssey, and Masamune Shirow’s Ghost in the Shell Volume 2: Man-Machine Interface, is a comic that exists because its author is too well-regarded to be said “No” to. The graphic novel is the first work of longform narrative fiction from the cartoonist in ten years and represents a return to praxis from a creator best known for his educational comic trilogy: Understanding Comics, Reinventing Comics and Making Comics.

Because of these three books — taught in high schools and colleges, lauded by high-profile writers and artists, and garnering McCloud countless speaking engagements — the man is widely regarded as a guru by aficionados in the medium. In The Sculptor, McCloud harnesses the techniques, tics and tricks he examined in those books and applies them over the course of 500 pages. He does an excellent job of establishing a sense of place and space, using what he refers to in Understanding Comics as “aspect-to-aspect” panel transitions, using color and hatching to manipulate atmosphere and tone. His acting (rendering of specific and affective facial expressions) hits with pin-point atmosphere. McCloud’s panel-to-panel syntax also remains sharp. The book establishes an internal tempo, spreading moments across enough panels so that each beat is played out, the reader’s eyes linger for a second longer and any one moment carries elegantly.

Unfortunately, this competent application of technique falls in service to a story that fails in every conceivable way to connect, whether through coherence, originality, functionality or emotional consequence. At nearly 500 pages, The Sculptor is a weighty book with ample space to fully explore a heady, thoughtful story. But McCloud is unable to render a single character interesting, accurately depict the passage of time — months will appear to have passed and then a character will chime with “That last week”—or maintain a consistent, internal logic.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-