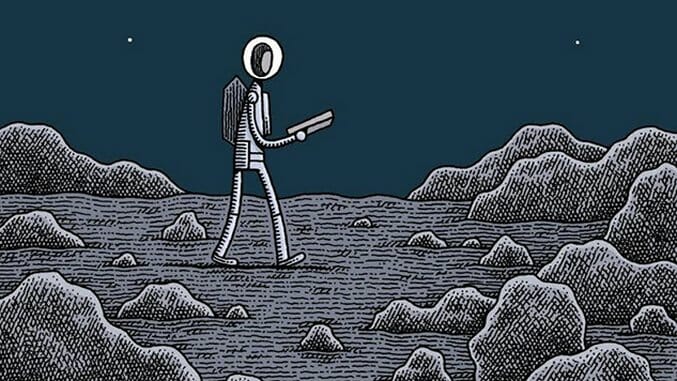

Mooncop Cartoonist Tom Gauld on Isolation, Nostalgia & Robot Cruelty

Tom Gauld is the book-lover’s cartoonist. His comics appear regularly in populist high-minded publications like The Guardian and New Scientist, where they focus on literary genres, both fiction and nonfiction. They’re silly, but in a serious manner, where a sandpaper dry delivery renders the absurd amusing. Gauld demonstrates a very British way of executing humor—the appearance of noisy attention-grabbing is strenuously avoided for more casual methods of engagement. At the same time, the comics swim in melancholy, even when they aim to make you giggle. Gauld’s simplified forms, which often appear in silhouette, have skinny arms and legs. If they have faces at all, he often defines those faces only with eyes and an occasional nose. This visual technique, along with the figures’ restrained body language, can make the characters seem down, and an atmosphere of failure pervades the strips (because failure is much funnier than success).

Mooncop, a short graphic novel by Gauld released by Drawn & Quarterly, falls along these same lines, but the payoff is a slower build. It can still be read in a single sitting, but the focus on one isolated character builds empathy over time. Jokes still flourish (i.e., cops love donuts, even in the UK…and even on the moon), but they’re more situational and less gag-based. It’s also a pleasure to see Gauld flesh out a world, even if it’s a rather airless one devoid of humans—save one. So does the cartoonist live in a Victorian-era bubble? Would he be happy being the last man on the moon? And how does he really feel about robots? Read on and find out.

![]()

Paste: Talk to me about the difference between crafting a stand-alone cartoon (whether or not it has several panels) and a longer narrative. Is the act of inspiration similar or not?

Tom Gauld: The two are very different and I think that I’m more naturally suited to making the short cartoons, which explains why I’m rather slow at making the longer books. The cartoons I make for The Guardian or New Scientist generally have between one and eight panels, and I think that for something of this size you can take just one nice little idea, execute it well and hopefully you have a successful cartoon. There isn’t space to cram in too much, or to overthink things, which is good as I have quite tight deadlines for these. For a longer story, I think you need either a bigger idea which can be explored more in-depth, or a series of interconnected ideas.

With my short cartoons I can take a chance on an idea and tell myself, if it falls flat I’ve got another chance next week, whereas you’ve got to commit a bit more to a longer story. Writing Mooncop (and Goliath, my other graphic novel) was much harder than making the shorter cartoons, but I do relish the bigger canvas.

Paste: So do you outline a lot for your longer works? How do you know if you have enough material to create a full graphic novel?

Gauld: Yes, I do a lot of outlining and planning and editing. I’m quite jealous of cartoonists who can set off on a story without a detailed plan. With Mooncop I was simultaneously making lots of sketches, designs and notes in my sketchbooks, while also typing dialogue and scenes. I just kept going till I had enough scenes to tell the story and give an atmospheric impression of the setting. I then drew the whole book in pencil and let a few people read it. After that I edited it some more, then drew the ink version. It’s quite a slow process, but it works for me.

As for the length of a graphic novel, Art Spiegelman wrote an interesting piece in a recent New Yorker (or maybe it was just on the website) about one-page graphic novels. He argued that the term could be used without a connection to a prose book idea of length. You might say that Mooncop is a graphic novella, but my aim was just to make something which worked as a story and not to worry too much about length.

Mooncop Interior Art by Tom Gauld

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-