30 Years Later, Watchmen‘s Unacknowledged Optimism Persists

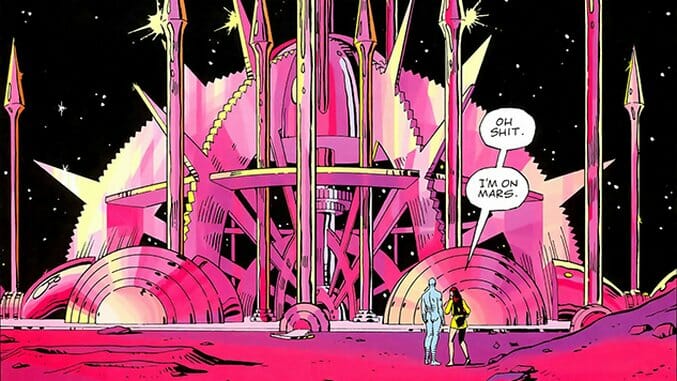

Main Art by Dave Gibbons

“Nothing ends, Adrian. Nothing ever ends.”

Three decades to the month have passed since Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons put those chilling words into the mouth of Dr. Manhattan, delivering the atomic man’s parting wisdom to humanity before he leaves to create life on other planets. In the 30 intervening years, Watchmen’s influence on comics and the movies they’ve spawned has reached unfathomable depths. For better or worse, it (alongside Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns) killed the unperturbed, morally pure superhero and gave us hundreds of stories that lurk in the gray areas, so many that Moore himself became upset with the bevy of writers pursuing grit for grit’s sake.

I don’t need to sit at my computer and tell you how amazing Watchmen is on its literary merits; in case you needed a reminder, check it out on Time’s list of the 100 best English-language novels (not just comics—novels) published since 1923. I do have a personal testament I’d like to add, though: back in high school, I was a quiz bowl nerd. Among the many categories of questions my teammates and I had to answer was literature, which typically meant fine literature—your Nerudas and Hemingways and Shakespeares of the world. The only graphic novel I can ever recall being asked about in quiz bowl? Yep, you guessed it. Ten points for you.

Watchmen Interior Art by Dave Gibbons

It’s customary to reminisce on a classic work whenever it celebrates an anniversary, but in the case of Watchmen, I think a retrospective couldn’t come at a better time. Thirty years ago, the United States and the Soviet Union were still locked in a seemingly interminable power struggle. Osama bin Laden was leading a group of guerrilla warriors against the Russians in Afghanistan, and “fundamentalist Islam” was an enemy that had briefly taken over the American consciousness during the Iranian Revolution, but had lain dormant ever since. Everything else, from the trending world AIDS epidemic and the way we shared information to the culture that received such a loving homage in Stranger Things, was different, too.

But if you reread Watchmen, the most important difference you notice between its world and our own is that the Cold War, and especially the escalated fear of nuclear warfare that characterized the Reagan years, dominates the novel’s spirit. In fact, had villain Adrian Veidt not unified the world by killing three million New Yorkers with his fake alien attack, the story suggests that America and the Soviet Union would have blown each other to bits soon thereafter.

Veidt, who formerly went by the moniker Ozymandias, and his plan are an element of the book I’ve struggled with a lot over the past year. It succeeds, of course, putting his (former?) friends in agonizing moral checkmate and resulting in the death of the uncompromising doom-and-hellfire vigilante, Rorschach. But the ending seems to be a bit of a cop-out, a departure from Watchmen’s reverent realism just to bring about the most convoluted “happy” ending ever conceived. There’s no chance in hell that Veidt’s plan would succeed in uniting today’s world. Religious extremists might claim the alien as a sign of coming apocalypse and redouble their efforts to bring about their kingdoms of god. The United States and China might find some economic common ground, but would Vladimir Putin be a team player? Kim Jong-Un might just finally say “fuck it” and, in a drunken rage, launch all his nukes at South Korea and Japan. Regardless of what would actually happen, 2016 has shown us enough deeply rooted schisms, in both global and domestic politics, that you’d have to be naive to imagine even the most explicit of extraterrestrial threats holding humanity together for more than the lifespan of a few tweets.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-