Artists Explore the Many Faces of Evil

Photos courtesy of the Jewish Museum of Florida-FIU

The Oxford English Dictionary defines “evil” as “profoundly immoral and wicked.” Ask most people, and that would mean torture, genocide, slavery and human trafficking.

Often what is considered an evil act will depend on a certain level of carnage. But not all atrocities are bloody and brutal; some are not even executed on a mass scale. Evil can also be insidious in nature—a malicious deed obscured by formality.

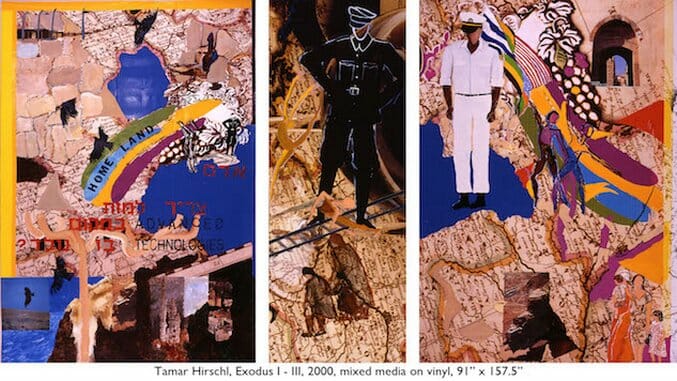

This premise is at the core of Evil: A Matter of Intent, a new art exhibition that opened April 20 at the Jewish Museum of Florida-FIU in Miami Beach and runs through October 1. The show features more than 70 artworks, spanning seven decades, that explore the many faces of evil—from the Holocaust and lynchings to the War on Women and lack of gun control.

“People don’t think about these things as evil,” said Jackie Goldstein, curator at the Jewish Museum of Florida-FIU. “[But] evil is not just terrorism.”

Evil: A Matter of Intent is a lesson on the subtlety of inhumanity in the midst of great barbarity. There are some pieces that show the most obvious manifestations of evil, such as Paul Margolis’s photograph, “Burning Towers 9/11/01,” which captured the first World Trade Center tower burning minutes before its collapse. Then there are other works of art that examine the consequences of brutal acts long after they’ve occurred, such as Leonard Mejselman’s “Hiroshima, A Child’s Shirt,” a semi-abstract painting meant to symbolize the enduring aftereffects of the atom bomb.

Nearly three dozen contemporary and modern artists contributed work to Evil: A Matter of Intent, which initially ran last year at the Hebrew Union College Jewish Institute of Religion in New York City. Its curator, Laura Kruger, first conceived of the exhibition after flipping through an issue of the New York Times over Sunday brunch and realizing each headline was “more terrible than the last,” she said.

But Kruger noticed a trend while reading the Times that day. The reporters weren’t covering natural disasters that devastated neighborhoods or wildfires that ravages rural communities. Instead, these terrible headlines “all came from one core: deliberate acts from politicians, leaders, wealthy people,” she said.

In putting together the show, Kruger wanted to both tackle and challenge what constitutes an act of malice—hence the name, Evil: A Matter of Intent, she said. “The denial of education. The denial of clean water. That’s evil, too.”

Not all of the artists featured in Kruger’s show in New York City have work hanging at the Jewish Museum of Florida-FIU. There are also some pieces special to the museum’s collection that Goldstein added to the Miami Beach exhibit, such as the red Ku Klux Klan robe she draped on a hulking mannequin.

Goldstein said she experienced “a lot of anger” when curating Evil: A Matter of Intent at the Jewish Museum of Florida-FIU. She said she often found herself questioning why people let these atrocities occur—why they didn’t do more to stop the Holocaust, the genocide in Rwanda and other horrific events throughout history. Goldstein hopes, though, that this exhibition sparks dialogue so that people “won’t stand by next time.”

“This is not an easy subject,” she said. “I want conversation to happen even if people disagree.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-