It’s Time for a Malty Beer Revival

Photos via Unsplash, Ashim D’Silva, monica di loxley

In the last few years, if I’ve taken the time to sit down and put digital pen to internet paper registering an opinion on the state of the craft beer world, it’s often been to voice disappointment in how the industry seemed intent on backing itself into an increasingly stagnant position. As early as 2018-2020, I had grown weary with the vogue of incredibly hop-saturated hazy IPA, and the way they had seemingly obliterated any sense of proportion or the expectation of subtlety in drinkers. I mourned as iconic breweries that previously served as champions of stylistic diversity in earlier eras of the craft beer experiment, such as Sierra Nevada, eliminated almost all of that diversity from their yearly release schedule in favor of iteration after iteration of the same thing. And finally, just last month I effectively put my hands up in the air and acknowledged that I don’t know how the beer world can ever really regain its appreciation for a wider array of styles and flavors, in a time when almost everything is grouped under a sweet, juicy, fruity banner.

I can think of one thing that certainly wouldn’t hurt, though: A malty beer revival. Rather than simply bemoan the state of India pale ale here once again, I thought it might be nice to reflect and wistfully consider some of what we’ve been missing in recent years–beer styles and flavors that drinkers newer to craft beer might barely even have encountered in the wild at this point. And there’s no corner of the beer world that is generally more underserved in this point of time than styles that are malt-forward.

What do we even mean, when we call a style “malty” or malt-forward, though? What qualifies as malty beer? Which styles exemplify what these flavors are all about? And do craft brewers have any hope of generally selling enough of them to make these styles viable on a national stage, beyond the limited brands that are still out there?

The Flavor of Malt, and Malty Beer Styles

“Malt” is of course a reference to malted barley itself, the ingredient upon which modern beer styles are classically based. With that said, “malt” can also refer to other grains such as malted wheat or rye. But beer doesn’t technically need to be based entirely around malted grain, either–you can also use some unmalted grains, roasted or non-roasted, in making beer. There’s even a new brewery in New York claiming to specialize entirely in making beer from unmalted grains.

When we refer to “malty” beers, then, what we’re really saying, beyond just beers demonstrating the flavor of malted grains, is beers with grain-forward flavor profiles in general. Which is to say, beers where the most dynamic and assertive aspects of their flavor are being contributed by the grain bill, rather than by other elements such as hops or yeast. This is of course a wide spectrum–there are delicate beer styles such as kolsch that often spotlight gentle malt flavors, and others like barleywine that revel in dark, sticky malt sweetness. One kind of “malty” is nothing like another.

In a general sense, though, malt provides body, sweetness and grain-forward flavors in traditional beer styles. Through the careful use of numerous styles of malted barley or other grains, a brewer can dial in the exact profile they’re looking for, using tiny amounts of one malt or another to layer in flourishes of flavor, the way an artist might create layers of paint on a canvas.

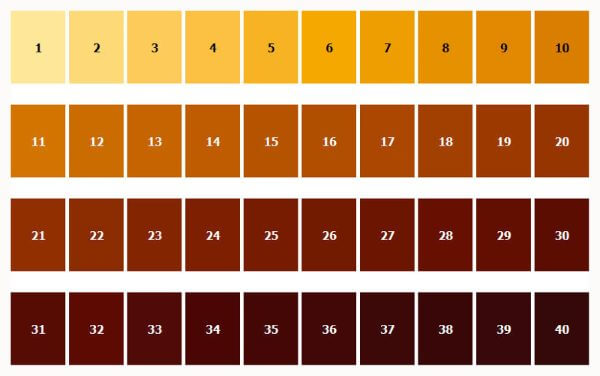

The SRM scale is effectively the malted barley rainbow.

Take a relatively simple ale style such as kolsch or generic American blonde/golden ales, for instance. These styles are likely to be based on some of the lightest (in color) malt styles available, such as pilsner malt, which contribute crackery, crisp grain flavors, and the only other malts used in most cases are likely to be equally light styles such as Carapils, used to enhance mouthfeel and head retention of your pint. Go a couple shades darker on the scale of beer styles and you’ll find something like American amber ale, which likely makes use of crystal malt (also known as caramel malt) or darker unmalted barley to achieve a reddish-amber hue and more pronounced toasted bread/caramel flavors. This progression continues right on through the darker, bready-doughy flavors of styles such as bock or dunkel, to the nuttiness of brown ale, the crisp roast of porter, or the dark, dried fruity complexity of barleywine, strong ale or Belgian quad. In all cases, malt is arguably the star of the show, though styles such as quad or barleywine are also showcasing dramatic flavor contributions from yeast profiles or the alcohol itself.

Unfortunately for lovers of these types of styles, however, they have not only increasingly receded into the background (especially in terms of shelf space in package stores), but often been modified in recent years to reduce their maltiness, rather than feature or celebrate it.

The Culling of Malty Beer Styles

There was a time, not all that long ago, when a relatively balanced beer list at a brewery taproom or brewpub was something one could reasonably expect. There have of course always been specialist breweries that focused heavily on one end of the spectrum or another, but in general one would walk into a business such as a brewpub expecting to see a healthy smattering of styles and strengths, including no shortage of malt-forward beer styles.

This began to rapidly change during the second big craft beer boom of the early 2010s, as the ascendance of IPA as the craft category’s standard bearer, and a new generation of hop-loving drinkers, resulted in a steady flow of new IPA brands and less focus on older (and often malt-forward) styles that were increasingly branded as passé and old fashioned. It wasn’t long before it was seen as perfectly normal for a brewery’s draft list to be 50-75% IPA, with all other styles now living on the fringes.

Perhaps more concerning to malt fans, though, beyond just the increased difficulty of finding those styles, was the fact that those styles were now often being redesigned to fit modern tastes by breweries chasing after the hop-addled clientele. India pale ale first became ever drier, as malt character became near impossible to locate, before ironically becoming far sweeter–not from malt, but from adjuncts and extreme rates of fruit-forward hops. The expected “malt backbone” once referenced in styles such as pale ale increasingly disappeared, while surviving styles such as amber ale, pale wheat ale or brown ale found their hop rates increased and malt character toned down to appeal more to IPA drinkers. Porter and stout increasingly ditched actual malt-driven flavors for the wide world of desserty adjuncts. By the mid-2010s, we had entered an era where malt-forward flavors were being shunned by many drinkers whether they realized it or not, and we still find ourselves in this position today. This holding pattern has stretched on for almost a decade.

The distaste for malt has become so pronounced, in fact, that major regional craft brewing powerhouses like New Belgium and Boston Beer Co. went out of their way to redesign flagship beers that had been associated with their brands for decades in 2023, in both cases with the primary goal seemingly being to cut down on the malt presence in those brands. Look at the wording used by both companies in marketing their new versions of Boston Lager and Fat Tire, a brand that no longer bears the previous “amber ale” label at all–they’re now referred to as being more “crisp” and “bright,” terminology designed to highlight a “lighter” profile that isn’t bogged down by the apparently “heavy” addition of malt. It doesn’t matter if a robust malt presence has been associated with these former flagships for literally decades; those flavors just aren’t welcome in the current landscape.

What we have instead is an apparent preference for dual extremes in so much of the beer brands that can currently be found on package store shelves: Either extremely crisp and light, or extremely bombastic, boozy or sweet. What has been trimmed most is that middle ground, which just so happens to be the area where many malt-forward beer styles have always lived.

Bring on the Malty Beer Revival

Today, on the rare instances when I run across a nice, subtle, malt-forward beer style in a brewery taproom, I occasionally find myself wondering what percentage of beer drinkers who discovered the craft beer world in the last five years have even properly experienced what these flavors are all about. There’s nothing at all wrong with a drinker who got hooked on craft beer for the first time through juicy, hazy IPA in the late 2010s–the industry would be in an even rougher place today without these consumers–but how many of them really know the pleasures of a well-made Vienna lager? How many have experienced German pilsner that actually has a malt backbone to it, as the BJCP description of the style goes out of its way to note: “The hops are moderately-low to moderately-high, but should not totally dominate the malt presence.” How many are aware of what standard-strength porter and stout taste like without half a dozen adjuncts also involved?

It’s probably wishful thinking to imagine these consumers experiencing these new–to them–malt flavors and subsequently falling as passionately in love with the lesser-seen beer styles as they did with the likes of IPA. But it probably wouldn’t hurt the economic viability of a style like amber ale, either, to have a new generation of consumers realizing for the first time what actually makes a style like amber ale distinct in the first place. And that boils down to a celebration of the flavors of malt, the building block where beer begins. Who knows? Those consumers might start seeking out more beers with flavors you could describe as toasty, or nutty, or grainy, with caramel or malty-sweet highlights. Perhaps then they’d even look back at the IPA they’d been drinking and regard it with a bit more desire for balance, rather than as a vessel to deliver as much “juice” as possible.

Consumers will of course need to do their part, by buying and supporting these malt-forward beer styles whenever we have a chance to encourage a bit more diversity in the lineups of our local craft breweries. But perhaps more than anything, we should be trying to expose the simple pleasures of these styles to drinkers who may not be familiar with them, a process that could hopefully broaden the tastes of a generation of newer craft beer drinkers whose options have often seemed unexpectedly limited.

Do I expect to ever see my local taprooms full of bock, brown ale or malt-balanced pilsners once again? Likely not–this feels like an era of the craft beer experiment that has come and gone. But the more we evangelize for those sorts of styles now, the better off they’re likely to be whenever the current wave of hop saturation finally recedes. And for the sake of all the malty beer fans out there, I hope it won’t be another decade before that happens.

Jim Vorel is a Paste staff writer and resident beer and liquor geek. You can follow him on Twitter for more drink writing.