Searching for Rum and Salvation in the Caribbean

Photos by Jerard Fagerberg

The first time I ever drank rum was spout-to-lips from a plastic gallon in a fraternity basement. I knew then why the early settlers called the spirit “Kill Devil.”

Now, I treat rum like a bodega cat and leave it alone unless it approaches me. When I do drink rum, it’s Bacardi shaken in a bottle of Sprite or God-knows-what blended with ice and too much grenadine. Never have I taken a swig of a Cuba Libre and pondered the vintage.

The American craft distilling movement is doing its best to redeem the name of rum, but Bacardi still represents a third of the overall market, with Captain Morgan closely behind. Though both megabrands are losing market share annually to upstarts like Cane & Abe and Dancing Pines, the indignity has been culturally absorbed.

But rum is a drink of resilience. It has built nations, fueled navies, and perpetrated countless evils. It was the spur of an industry that transformed a region — a history so potent it can’t be drowned in sugar.

In order to learn this, you need to put aside the Sunday hangovers and pina coladas. You need to leave the United States and drink with untainted lips. So that’s what I did. Courtesy of Cheap Caribbean, I booked a five-day tour through the islands of Antigua, St. Kitts, and Barbados to try and reclaim a relationship with the spirit that’s been haunting me for the past decade.

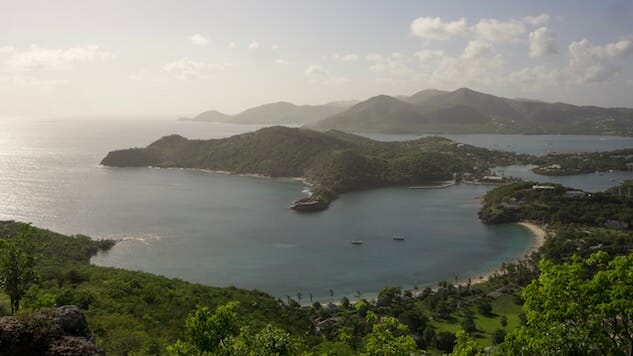

First drop in the rum barrel: Antigua & Barbuda

Antigua was nearly destroyed in 1995 by Hurricane Luis, greatly setting back its development into a glossy tourist island. It has an almost Southeast Asian feel, with sewers running along the streets uncovered. Following Irma, it’s become a hospice for devastated sister island Barbuda. Our first stop, Antigua Distillery Limited, feels more like an oil derrick than a distillery, but it’s a monument to the resiliency of the storm-battered island.

ADL was founded in 1933 by rum shop owners. Rum shops are keystones in Caribbean society, and the proprietors of these bodega-like neighborhood bars would take rum from distillers, mix it with caramel or other sweeteners, and create signature blends. The directors of ADL wanted to control the production of rum from the beginning, and so they chartered a piece of land on an island no one wanted and have been making the only island-distilled rum ever since.

As we open the van door, the smell of molasses floods in. Molasses is the raw material for rum — once a byproduct that was dumped into the sea by sugarcane refineries, molasses became the brown gold of the Caribbean when slaves discovered you could ferment it into liquor.

As ADL sales and marketing executive Calbert Francis tells us, the sugar plantations of old are now gone from Antigua. The molasses fermented at ADL is shipped in from Guyana or, more recently, Panama. Tourism has taken over as the flagship industry, accounting for over 50% of the country’s GDP, and tourists like to drink. ADL makes 9,000 barrels of rum per batch, processing it through their traditional all-copper column still. The history of the distillery is cached all over its tanks and scaffolding, and they outfit us in hairnets and hard hats before letting us climb up to the fermenters.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-