The Beginner’s Guide to Craft Tequila

Photo by T Photography/Shutterstock

For most of us, tequila is associated either with pitchers of margaritas on the patio, or two or three too many shots followed by spending the wee hours in the morning leaning on the porcelain throne. That kind of tequila, however, is the cheap stuff, and there is a lot about tequila that is far from cheap.

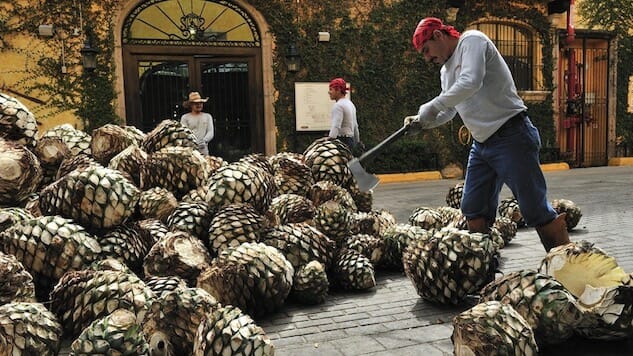

Unlike a spirit like vodka, which can be made anywhere and from just about anything that ferments, tequila mostly gets made in the Mexican state of Jalisco and only from blue agave. This plant takes up to a decade to mature, and the huge, pineapple-like core that is used to make tequila must be harvested at just the right time and, by and large, by hand. These are then baked, and then crushed to extract the juice, which is then fermented and distilled to between 55% and 60% ABV.

At that point, the liquid is blanco, or clear tequila, and even at that most basic point you have a spirit based on a plant that takes years to grow and requires skilled labor to get the most out of at harvest. Next, a tequila-maker can add more expense to their product in the form of barrel aging. When tequila is matured in wood, it becomes either reposado (“rested) after two months, anejo (“aged”) after at least a year, and extra anejo, which is tequila that has been aged even longer. The size and origin of the casks used for aging tequila can vary, but ex-bourbon barrels from the U.S. are the most common.

Interest in higher-grade tequila has grown in recent years, and with it has come craft tequila. If pursuing good tequila is your aim, then your central concern is the native flavors of the blue agave. So, the first thing you want to avoid are mixto tequilas, which are not 100% agave. Another trap to watch out for is the gold tequilas, because while some are mixtures of silver and reposado, most just have some caramel coloring and/or oak extract added.

Here are some factors to look for in assessing the craft and quality of a tequila.

Was the agave baked in a horno? In traditional tequila making, the agave is slow baked in a masonry oven, rather than fast-cooked in a pressure cooker. Many experts feel that pressure cooking the agave homogenizes them, which is great for making a consistent product, but not so much if you are trying to maximize things like terroir.

Was it distilled in a copper pot? Likewise, most believe industrial column stills strip out the oils and other compounds that allow the agave spirit to retain its native flavors, and prefer tequilas made using copper pot stills instead. It’s an idea any Scotchophile will recognize, with column vs. pot stills being one of the major distinctions between malt and grain whisky.

Aged, but not too aged. Tequila can pick up some good qualities from barrel aging, but too much of it is usually a bad thing, with the oak flavors smothering the more delicate agave. In this respect, tequila is more like wine than whiskey, as wine is rarely barrel aged for more than two years.

Look for terroir. Agave grown in the Highlands, south of Guadalajara, is slower growing but sweeter. Agave from the Lowlands is earthier and/or herbal. Some brands base their identity on using just Highland or Lowland agave, while a handful narrow down to agave from a particular estate.

So, the next time you are out for margaritas or palomas, check out what your local upscale cocktail bar has on offer and what they are using as a base. If a Manhattan can be improved by using $75 bourbon, why not other drinks and shots by using upscale tequila? Here are five craft tequilas to get you started.

Don Julio Resposado ($43)

Don Julio is a big, Top 10 selling tequila brand, but relies heavily on old school techniques, such as their masonry ovens and the wild yeast used in fermentation. They are also famed for the care taken on the agricultural side of things, from growing to harvesting their Highland agave. Their 1942 Anejo and Extra Anejo are worth a look, but their Reposado is a showcase for what just a little barrel aging can do for a Highlands style tequila: sweet and backed up with vanilla, spices and a touch of nuttiness.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-