Cocktail Queries: What is Bottled-in-Bond Bourbon, and Why Should I Care?

Cocktail Queries is a Paste series that examines and answers basic, common questions that drinkers may have about mixed drinks, cocktails and spirits. Check out every entry in the series to date.

You may recall, from our 5 Questions on Bourbon piece a few weeks ago, that the term “straight” on a bourbon bottle essentially functions as a federal guarantee of a certain level of quality. This is because bourbon is pretty well-defined by the U.S. government, and words on bourbon bottles tend to have concrete meanings. In the case of “straight,” a whiskey bearing that label must have been aged for at least two years, with no additional colorings, flavorings or non-whiskey spirits added. It’s intended to let the consumer know: “Hey, I represent a bare-bones baseline of quality,” protecting the drinker from potentially buying a quasi-“bourbon” aged for only a few months.

The term “bottled-in-bond,” (BiB) on the other hand, might best be thought of as representing another jump forward in that same line of thinking and consumer protection. The term has more hurdles for a distillery to jump over, promising a spirit of reliable quality and strength. For more than a century, drinkers have been able to see the phrase “bottled-in-bond” and know what they were getting, although the term is now in the midst of a modern revolution.

To start with, though, let’s define bottled-in-bond bourbon. Note: The bottled-in-bond term can actually be applied to any U.S. spirit, but it’s only commonly used with whiskey, most often bourbon and rye.

Bottled-in-Bond Definition

To be labeled as bottled-in-bond, your average bourbon must meet the following requirements:

— The spirit must be produced in the U.S., during a single distillation season (defined as January-June, or July-December), at a single distillery. This alone makes bonded whiskey distinct from many straight bourbons, which can be intermingled whiskeys from multiple distillation seasons and distilleries.

— The whiskey must be aged in a federally bonded warehouse under U.S. government supervision for at least four years. It can be aged longer, but four years is the baseline, and the most common timeframe. If you see no actual age statement on a bonded whiskey, four years is often a safe bet.

— The whiskey will be bottled at exactly 100 proof (50% ABV), which traditionally has made bottled-in-bond bourbons a good source of “bang for your buck.”

— The label is federally required to identify the distillery where the product was distilled, and where it was bottled if different, for the sake of transparency.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

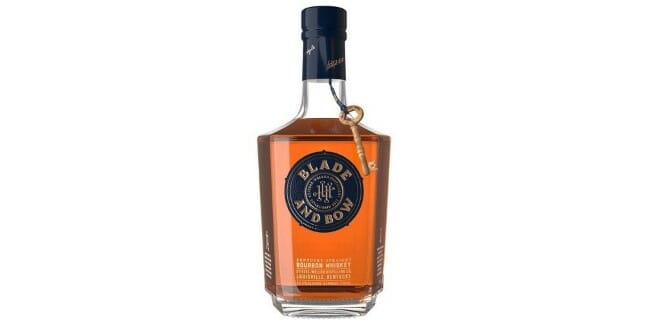

Though its design is a reference to federally bonded warehouses, Blade and Bow is ironically not actually a bottled-in-bond product.

Though its design is a reference to federally bonded warehouses, Blade and Bow is ironically not actually a bottled-in-bond product. A lineup of old-school BiB bourbon and rye.

A lineup of old-school BiB bourbon and rye. Members of a new BiB generation.

Members of a new BiB generation.