The “Fasting Girl”: A Victorian Phenomenon That Made Starvation Trendy

Photos via Unsplash, Thought Catalog

Even among the most inveterate of modern medical charlatans or dietary quacks, there are a few basic tenants of human existence that one expects to be accepted as universal. No one disputes that humans require air or oxygen to continue living, for instance. The fact that we also require food and drink for our continued survival should be just as apparent. Sure, it’s not hard to find quacks still pushing what amount to starvation-style diets, but this form of fasting is typically at least based on the acceptance that it’s a temporary lifestyle, not one that can be maintained forever. In 2022, you’d be hard-pressed to find many YouTube influencers pushing the notion that humans can live entirely without food and water.

And yet … that belief was once fairly commonplace in the United States, and in Europe. It was represented across several disparate social, religious and medical movements in the 1800s-1900s, all of which were ultimately pushing the idea that “man can live without food” for vastly different reasons. A beguiling mix of spiritualism, pseudoscience, religious devotion and deadly charlatanism all played their parts, giving us the phenomenon perhaps best encapsulated by the archetype of the “fasting girl.”

Fasting Girls and Psychic Powers

In 1864, a 16-year-old New York City resident named Mollie Fancher suffered a debilitating injury when she was thrown from a horse, her head striking the pavement. Only a year later, she suffered another catastrophic injury when her dress caught on a trolley car, resulting in Fancher being dragged for a block. Afterward, she suffered from fainting spells, violent headaches, and strangely began to apparently lose her physical senses: Touch, taste, sight and smell. Author Herbert Ashbury, who penned Gangs of New York, wrote the following about Fancher in his 1934 tome All Around the Town.

Her spine was injured, and her nervous system completely deranged. She was able to be about, though ill, until February 3rd, 1866. On the morning of that day … she suddenly shrieked, stood on her toes, and spun around like a top. Then she bent forward, clasped her feet in both hands, and began rolling about the kitchen floor like a hoop. She was carried to her bed, and didn’t leave it for fifty years and eight days, until she died, on February 11, 1916.

Confined to her bed in the decades to follow, Mollie Fancher (and her parents) began to claim that the girl had developed extrasensory powers. Dubbed “The Brooklyn Enigma” by the press, Fancher claimed to be able to read minds, or read the contents of a book by simply placing her hand on the cover. She offered prophecies, and her family accepted “donations” from curious Brooklynites who wanted to come visit the bedridden girl in search of miracles. And all of these wondrous abilities were attributed to one thing: The fact that Mollie Fancher claimed to no longer eat food or drink.

Fancher is one of the better-known cases of what came to be known as a “fasting girl,” a 19th century Victorian concept of much fascination—today, we’d almost call it a “fad.” These were inevitably young girls—the public was not interested in “fasting boys,” as they presumably lacked the virginal image of purity and piety that was required—who were confined to beds and claimed to be able to subsist with either no food/drink, or extremely small amounts of infrequent food. Many claimed to possess psychic powers, while others styled their fasting as a tribute of religious devotion, essentially casting themselves as saints-to-be. German Catholic mystic Therese Neumann, for instance, dubiously claimed to have consumed no food other than the Holy Eucharist for her whole life, and pretty clearly was driven by a personal obsession with living a life that could result in beatification/canonization. Many “fasting girls,” meanwhile, were essentially treated like sideshow spectacles, exhibited by their own parents or legal guardians, who inevitably were happy to accept “donations” to witness this wondrous event. In the midst of the 1800s/early 1900s spiritualism movement, the stage was set for con artists to jump onboard, or parents to simply find a way to profit off an infirm child.

Details about the day-to-day lives of fasting girls such as Mollie Fancher are, perhaps unsurprisingly, quite difficult to come by. There are accounts of Fancher going into “trances” lasting weeks, months or even years—the previously quoted Herbert Asbury claimed she spent nine years in a psychic trance in All Around the Town, while other accounts of Fancher mention nothing of the sort. Regardless, she apparently professed that she had begun eating again at some point in the 1880s or 1890s—one has to wonder if she’d gotten too old for the local press to still be interested in the “fasting girl”—and lived out the rest of her life outside of the media spotlight.

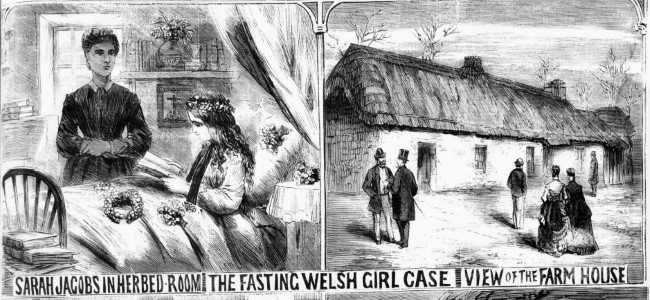

Other fasting girls, however, weren’t nearly so lucky. A particularly infamous case was the ordeal of Welsh preteen Sarah Jacob, whose parents claimed had lived entirely without food or water for several years. She quickly became a local sensation, with her parents gleefully accepting “gifts and donations” on behalf of the miraculous girl. Skeptical doctors, meanwhile, pressed for a test of Jacob’s abilities, and her parents eventually agreed for the claim to be tested under strict supervision by nurses from a London hospital. The nurses were told to provide food for Jacob if she requested it, but otherwise observe her 24 hours a day to confirm she wasn’t secretly receiving food from some other source. After a little more than a week, Jacob was dead of starvation—her parents refusing to the end to provide her with food, insisting that her failing health was unrelated. The parents of Sarah Jacob were subsequently convicted of manslaughter in 1870, and sentenced to hard labor.

Many such cases of “fasting girls” ultimately fell apart under similar types of testing or observation, or were generally so suspicious in what testing the family would allow that the public eventually assumed they were hoaxes. Some of the methods used by imposters such as Ann Moore were particularly absurd sounding when viewed through the modern lens—she reportedly received smuggled food from her daughter “via various means, including by putting a towel soaked with broth over her mother’s mouth and conveyed food from her mouth to her mother’s while kissing her.” Imagine being that desperate to continue convincing strangers that you didn’t need food to live.

In the course of modern investigation, the cases of the various fasting girls have been advanced as probable early evidence of the disorder we now know as anorexia nervosa, although the spiritual and religious entanglements in many of the cases also suggest an earlier condition called anorexia mirabilis. Also known as “holy anorexia” and rarely experienced anymore in Western society, this was a faith-inspired form of self-starvation meant to purge the body of sin or impropriety by emulating the suffering of Jesus.

Self-starvation wasn’t only being promoted in this period by religious fundamentalists and spiritualist charlatans, however. Doctors with legitimate medical licenses were also pushing dangerous starvation treatments, while new, pseudoscientific movements were cropping up that blended fasting with New Age-style hucksterism.

Living on Air and Sunshine Alone

One may often see intermittent fasting touted by modern, Goop-adjacent mommy blogs and TikTok “health experts,” but the modern fascination with fasting is relatively structured and innocuous in comparison with the extremes to which fasting was often pushed in the 1800s and early 1900s. This was essentially a pseudoscientific extension of the spiritualist movement of the era, attempting to piecemeal cures to various diseases by combining supposed “ancient wisdom” with the popular fad treatments of the day, such as fasting and enemas. Combined with the celebrity-like status of well-known doctors in this era, it set the stage for deadly consequences from medical professionals who unknowingly (or sometimes maliciously) starved their patients.

One of the more infamous of these charlatans was Linda Hazzard, who actually possessed no medical degree, but passed herself off as a healer anyway. As was common at the time, Hazzard established a Seattle area retreat/sanitarium in the early 1900s, in which she could essentially rule with an iron fist, treating her patients away from the prying eyes of family, friends or government regulators. And her preferred treatment method was a slow course of starvation, combined with “hours-long enemas” and physically aggressive massage. Patients of Hazzard often lived for weeks or months on little more than orange and tomato juice, while their mental and physical faculties slowly crumbled and they became weaker and more infirm. Hazzard, a consummate swindler, would then convince or force her weakened patients to sign over all their worldly possessions and property to her, which she would inherit after their deaths. In some cases, she reportedly forged patient wills herself, when they couldn’t be coerced.

Although some patients did survive their time at Hazzard’s sanitarium—she couldn’t very well kill all of them and hope to remain in business—dozens died while under her care, and the place became locally known as “Starvation Heights” as stories began to leak out. Hazzard refuted claims that her methods were hurting patients, claiming that the dozens who passed away in her sanitarium were dying of unrelated causes such as cancer. Things finally hit critical mass in 1912, however, when Hazzard was convicted of manslaughter following the death of Claire Williamson, a wealthy British traveler whose sister Dorothea was also being starved by Hazzard in the same sanitarium. At the time of Claire Williamson’s death, she reportedly weighed only 50 pounds, while Dorothea was almost as bad. Hazzard was subsequently sentenced to up to 20 years in prison, but she was released on parole only two years later before being mysteriously pardoned by Washington governor Ernest Lister. She lived out the rest of her life continuing to run similar scams, before ironically dying of starvation in 1938 while attempting her own fasting cure.

Other popular health movements, such as Natural Hygiene, recommended fasting as a cure for any and all ailments and diseases, becoming the central texts cited by the likes of Linda Hazzard and others. But these beliefs persisted throughout the 20th century, ultimately ascending to their most ludicrous level in the quack movement known as breatharianism. This is a potent blend of mumbo-jumbo, borrowing liberally from the Indian/Nepalese system of folk medicine known as Ayurveda, itself mixed into spiritual beliefs of Hinduism. According to promoters of breatharianism, the human body simply didn’t need food or drink … ever. What it really needed was the lifeforce known as prana in yoga and Hinduism, and the best sources of prana were direct sunshine and fresh air. Which is to say, breatharians ultimately believed that all their nourishment should come simply from sitting in the sun.

These beliefs were pushed by con men such as Wiley Brooks, who founded the Breatharian Institute of America (it still exists!) in the 1970s and became well-known in the U.S. through appearances on the TV show That’s Incredible! in the 1980s. Brooks claimed that he was able to live entirely without food or drink, but simultaneously that he only had to resort to food when there wasn’t enough fresh air and sunshine available. That’s presumably what must have happened when Brooks was hilariously caught leaving a 7-Eleven in 1983 with a Slurpee, hot dog, and Twinkees. Never one to miss a chance for ridiculous hypocrisy, Brooks would later go on to claim that his “no food” beliefs specifically didn’t apply to McDonald’s cheeseburgers and Diet Coke, because the burger possessed a “five dimensional base frequency” that could help breatharians ascend to a higher plane of consciousness, while the Diet Coke contained, and I quote, “liquid light.” To repeat: This man’s philosophy was that the human body could run without any food or drink, but he left himself a carve-out to conveniently eat McDonald’s whenever he wanted, just in case.

Ultimately, pseudoscience belief systems and cultish organizations such as breatharianism have always popped up primarily to enrich the false doctors and teachers who would purport to offer us the keys to immortality. It’s something one may want to consider, the next time a TikTok personality swears by the latest “cleanse” or fasting-based fad diet as the secret to healing all of their woes. Finding a “fasting girl” ultimately isn’t all that difficult. Finding one that isn’t full of BS, on the other hand, is a bit more of a challenge.

Jim Vorel is a Paste staff writer and resident beer and liquor geek. You can follow him on Twitter for more food and drink writing.