The League Documents a Well-Rounded Chapter in Baseball History

You don’t need encyclopedic baseball knowledge to appreciate Sam Pollard’s new film The League, but it probably helps. But despite Pollard’s rigorous scholarship in his subject area, The League isn’t a dense movie. It’s just painstakingly researched and judiciously constructed. What Pollard pulls from his subjects is ease of storytelling; even at an hour and forty minutes, the film keeps a lively pace, and for all of the work’s academic value, it’s endlessly, almost effortlessly engaging. Pollard didn’t make this movie just for folks with heads for sports stats. He made it for everybody.

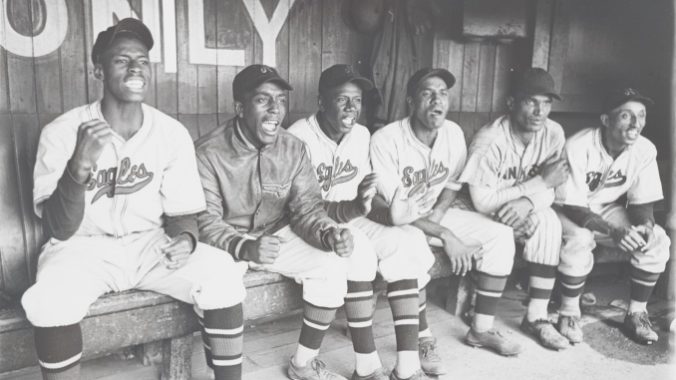

This nicely contrasts with the unflattering history The League confronts in chronicling the Negro Baseball League, namely that baseball wasn’t made for everybody, not to start with; it was made for the ruling body, white people, with Black people ad-libbing and making do with the resources they had available to them, and, miraculously, thriving beyond even their own expectation in the doing. Pollard understands that his audience must be broad, and accepts that his material will consequently brim over with important details: The names, places, dates, and contexts not only that drove Black Americans to form their own baseball teams, but made those teams successful. Any number of canonized aphorisms can explain how, and why: Scarcity drives demand; necessity is the mother of invention; life, lemons, lemonade. Pollard chooses to go deeper than that.

He also chooses to frame “success” as multi-dimensional when another filmmaker might have made other facets secondary to profit – which was, after all, part of the Negro leagues’ accomplishments. (This is America, and in America, we measure worth through pocketbooks and bank accounts.) For Pollard’s film, the leagues’ profitability is remarkable because that profit is so entwined with other markers of success and achievement and cultural vibrancy. So The League dutifully minds profit while paying greater attention and homage to people. Again and again, Pollard brings the film back around to strokes of either entrepreneurial brilliance, embodied in the actions of such figures as Rube Foster and Effa Manley, or circumstances like America’s entry into World War II, which, while not explicitly good fortune, benefited the leagues in some way. Almost every time he does, The League reflexively punctuates the relationship between baseball and money by establishing both as signifiers of healthy Black communities in the cities where the game was played.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-