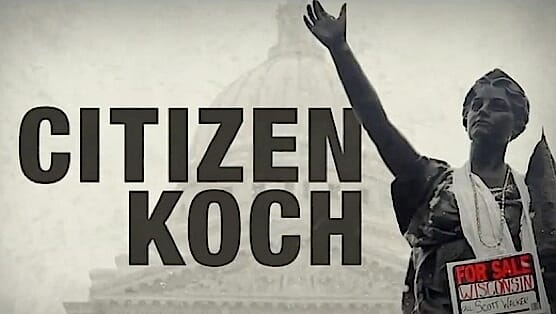

Citizen Koch

Citizen Koch opens with an old quote from Fred Koch, co-founder of the John Birch Society and patriarch of conservative billionaire brothers Charles and David Koch, about the “colored man” being part of the communist plot to take over America. The documentary then pivots into a sound bite of Sarah Palin offering up banal demagoguery in squawking fashion, before winding its way through an opening credit sequence that offers up no shortage of race-baiting bile. So co-directors Carl Deal and Tia Lessin’s dyspeptic film is in many ways a willfully queasy experience for Democrats, or even those who simply don’t like inflamed and ill-informed rhetoric in their political posturing. But, separate and distinct from being utter catnip for politicos, the dark lessons this engrossing nonfiction film holds—of entrenched power’s rapacious appetite for more power, and the destructive and fundamentally dishonest lengths to which its brokers will go to achieve their aims—are terribly important ones.

After sketching out a history of the Supreme Court’s controversial and unhelpfully broad 2010 Citizens United ruling, which rolled back fairly modest bipartisan campaign finance reforms and laid the groundwork for record levels of shadowy political fundraising, Citizen Koch connects the rise of the Tea Party to super-PACs like Americans for Prosperity, founded and funded by the aforementioned Koch brothers. (Largely unexplored is the complementary rage-megaphone afforded them by a partisan cable news network.) The result: a record $3.5 billion spent on 2010 midterm elections.

There’s a deftly interwoven strand of the film that follows the quixotic campaign of Buddy Roemer, a happy warrior who, despite being both the former governor of Louisiana and an ex-Congressman, can’t secure a spot in any of the 2012 national Republican presidential debates, all for lack of fat-walleted benefactors. When he compares money in politics to guns—in that there is a power that comes with its execution, as well as merely the implied threat of its use—it seems more than just appropriate; it comes across as powerfully clarifying on a foundational level about the rhetorical priorities of one of the nation’s two national political parties: guns and money, money and guns.

Most of Citizen Koch, however, is framed as an exploration of the June 2012 Wisconsin gubernatorial recall—using the $64 million voter-initiated election (almost $46 million of which was spent on the GOP side) as a detailed, ground-zero case study for the fight over transparency, the will of an electorate and the corrosive nature of unchecked money in politics. Two years earlier, Scott Walker was a Republican rising star who declared his state “open for business” on the evening of his election victory. Then he promptly began doling out tax breaks to corporations and millionaires while also reducing health benefits for state employees and aiming to strip them of their collective bargaining rights. The last measure in particular struck many Wisconsinites as grossly unfair, and lit the fuse for his recall.

Citizen Koch, then, takes as among its most central figures three registered Republicans (a teacher, a correctional officer, and a military retiree and part-time craftsman) who each make between $42,000 and $50,000 annually, and are union members or related to the same. Deal and Lessin, Oscar-nominated for 2008’s Trouble the Water, have an openhearted everyman touch, and music by composer Neil Davidge captures the roiled sweep of this re-election fight.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-