Claude Chabrol’s Entertaining, Insightful Lies and Deceit

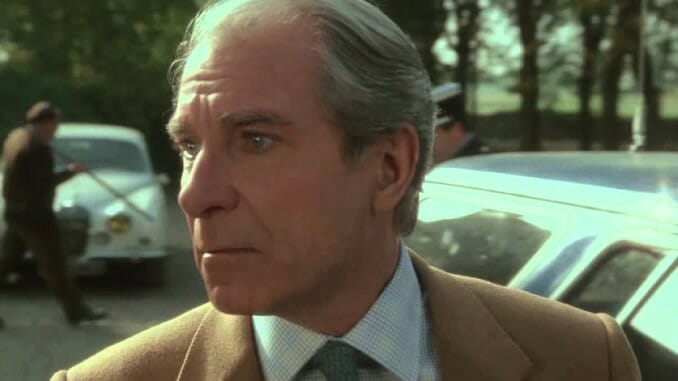

The least substantial movie in Lies & Deceit: Five Films by Claude Chabrol, Arrow Video’s tribute to the late, great French New Wave director, also happens to best embody the set’s spirit: In Inspector Lavardin, nearly everyone’s a deceitful liar, even the amoral police detective himself (played by the equally great, tragically late Jean Poiret). Lavardin passes off someone else’s family photo as his own in order to engineer an excuse to leave town; Raoul Mons (Jacques Dacqmine), the priest whose murder Lavardin means to solve, is a big time creep; layabout Claude (Jean-Claude Brialy) and his sister Hélène (Bernadette Lafont), Raoul’s widow, both know a little bit more about his death than they let on; Hélène’s daughter, Véronique (Hermine Clair), isn’t as innocent as she acts.

Everyone’s guilty of something, in other words, except for Lavardin’s chaperone, Marcel Vigoroux (Pierre-François Dumeniaud), a policeman in Dinard, where the film is set. He’s just doing his job. There’s a bitter comedy to his forthrightness in contrast to Lavardin’s unethical approach to law enforcement, just as there’s a bitter comedy to how well Inspector Lavardin sums up Lies & Deceit’s unifying motif. Chabrol was famously known as “the French Hitchcock.” Inspector Lavardin hews close to Hitchcockian principles of storytelling as the most accessible mainstream film of the lot: Madame Bovary, Betty, Torment and, of course, Cop au Vin—Chabrol’s first Lavardin picture, where Lavardin plays a supporting part in the ensemble instead of serving as the story’s centerpiece.

It speaks well of Chabrol’s gifts as a filmmaker that he so seamlessly weaves the same idea through each of these productions despite their wildly different genres. A pair of provincial whodunits; a character study of one woman’s interior life and sexuality; a bleak paranoiac domestic thriller; an adaptation of Gustave Flaubert’s classic novel of marital dissatisfaction. In some cases, Chabrol makes clear who is lying in his movies and who is telling the truth. In others, notably Torment, he leaves judgment to the audience—a form of torment unto itself. When we’re privy to the truth the characters in these movies are denied, we’re able to simply enjoy them as expertly crafted entertainment. When we’re forced to guess for ourselves whether there’s a lie in the air or not, we have to grapple with uncertainty.

That’s what makes a movie like Torment art and not a lecture, and perhaps why Inspector Lavardin was received by the New York Times’ Caryn James as “a trifle” (but a trifle to savor, as the rest of her review makes clear). It’s a mystery. Chabrol doesn’t give the game away until the end. But before he makes his climactic reveal and shines bright light on falsehood and chicanery, he expends little effort to cover the fact that Lavardin is surrounded by a pack of fibbing cheats. Rather than tell the viewer that everyone’s a suspect, Inspector Chabrol underscores that everyone’s in on or aware of Raoul’s murder to varying degrees.

-

-

-

-

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 3:10pm

-

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:57pm

- Urls By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:57pm

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:55pm

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-