Define Frenzy: Camp as Disappointment in The Stepford Wives

“Define Frenzy” is a series essays published throughout Pride Month attempting to explore new queer readings or underseen queer films as a way to show the expansiveness of what queerness can be on screen. You can read previous essays form previous years here.

The Stepford Wives remake in 2004 came at a curious time for gay culture and its place in straight culture. It was in the midst of the gradual integration—or, depending on how you see it, assimilation—of predominantly white cisgender gay and lesbian people into mainstream culture, which is to say after the AIDS epidemic, after the freewheeling ’70s reaction to the initial battle for liberation in the late ’60s, after said majority in minority proliferated in American film and TV. But this was also before the SCOTUS marriage equality ruling, before the gargantuan ascension of Ryan Murphy and before the repeal of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell. The tools of white gay male culture found itself negotiating its own complex relationship to what, I think, many gay men would consider their bedfellow: housewives.

Not those housewives, but the ones in the drag of some postmodernist suburban nightmare, thrashing through both the 1960s and the early 2000s, swaying uncontrollably to Danny Elfman’s sinister lullaby. That Frank Oz’s remake and re-adaptation of The Stepford Wives was subject to rumors of on set tension, bad test screenings, reshoots and a release in 2004 to middling reception felt like it only reified the bizarre liminality of gay masculinity, misogyny, broken promises and self-loathing that the film itself is concerned with unpacking.

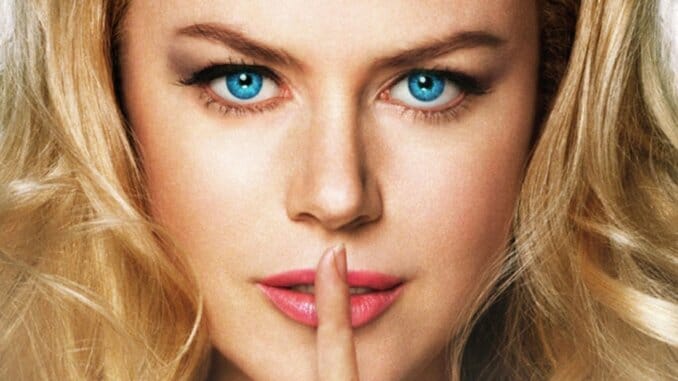

The updates to the film—which sends former TV exec Joanna (Nicole Kidman) and her family to the town of Stepford, CT, a town, you know, too good to be true—are not merely cosmetic changes to reiterate Ira Levin’s tale of (internalized and externalized) misogyny, power and marriage, but, if anything, a solidification of the strange, political reality-cum-terror of stasis and illusion. Levin’s imperfect critique of the struggles of Second Wave Feminism, and how easily the things fought for during that time could be taken away, looks back in anger, not to the future in trepidation.

The world that Joanna once inhabited was one where reality TV shows like The Bachelor and competition shows sought to undermine the “happiness” that a supposedly more equitable society was supposed to solve. Happiness and quality (not justice, mind you) could be monetized as a form of spectacle: One of the shows Joanna produced was called “I Can Do Better,” a vicious homewrecking as televised sport. A decade and a half removed, when even gays get their own reality TV dating show and Netflix is putting couples in pods so they can’t see one another before they propose, the pointed jokes in Oz’s The Stepford Wives feel increasingly prophetic.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-