Walt Disney’s Century: The Black Hole

In the midst of Star Wars mania, Disney made a disturbing, trend-chasing sci-fi throwback

This year, The Walt Disney Company turns 100 years old. For good or ill, no other company has been more influential in the history of film. Walt Disney’s Century is a monthly feature in which Ken Lowe revisits the landmark entries in Disney’s filmography to reflect on what they meant for the Mouse House—and how they changed cinema. You can read all the entries here.

Disney’s two unofficial rules these days seem to be making money and having a minimum bar of quality—or at least of craft. It’s unfortunate, because those two things often translate into exasperatingly boring art. The other inviolable dictate, for a big chunk of the company’s history, has been to be family-friendly, whatever that might mean at the time. (Now, that means acknowledging the existence of non-straight people and casting women and people of color in lead roles. It did not always mean that!)

The Black Hole, the 1979 sci-fi throwback that is unlike anything else the company has ever produced, is certainly well-crafted in its technical particulars: Computer-controlled camera rigs! New matte compositing that looks less janky! Tons of practical sets and props and detailed costuming! How did they make it look like there was actual zero-g on set??? (It was complicated wire rigs that they often made sure to film from below, and colored the same as the backgrounds whenever possible.) It is also Disney’s very first film rated raunchier than a G. The PG-rated The Black Hole (filmed and released prior to the invention of the PG-13 rating) features mild cursing, foul betrayal, the violent death of major characters, and an army of humans turned into robots through hideous necromantic mad science.

For all that noteworthiness, though, The Black Hole is… not a great film. But it is a bizarrely compelling first for the company, even if it is absolutely just chasing the trends of ‘70s blockbusters. Considering you can’t find other creepy stuff from that period on Disney+ (1980’s The Watcher in the Woods is a glaring gap in the catalog), it’s a miracle this thing is now widely available for viewing.

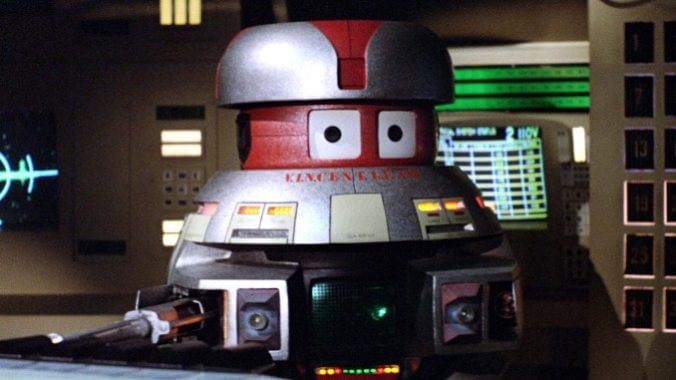

In some far-off spacefaring future (where all the same geopolitical boundaries are apparently still in effect and space crews are entirely white), the crew of the spaceship Palomino happens upon a massive black hole. This deep space phenomenon just so happens to have another spaceship orbiting it, strangely resistant to the gravity surrounding it. The cast is stuffed with actors you’re likely to know from other stuff: Anthony Perkins is the ship’s science officer, Robert Forster the no-nonsense captain, Ernest Borgnine a craven crewman, and the ship’s hovering smart-aleck jack-of-all-trades robot V.I.N.CENT. is voiced by Roddy McDowall. Joseph Bottoms and Yvette Mimieux round out the cast as the young hotshot and a young woman with ESP whose father disappeared—the ship orbiting the black hole was his last known location.

Aboard the ship, the Palomino crew is quickly disarmed and apprehended by a robot army, discovering that the ship’s only surviving crewmember is mad scientist Dr. Reinhardt (Maximilian Scheller—the hulking robot enforcer is named “Maximilian” after him).

Reinhardt has survived aboard the ship for 20 years using his genius and army of robot minions, studying the phenomenon of the black hole the entire time. He’s determined to travel through the black hole, claiming that there must be another reality on the other side, one that he will pioneer.

Everybody but Perkins’ scientist immediately comes to the conclusion that Reinhardt is cuckoo for Cocoa Puffs, and their independent wanderings around the ship immediately bear this out: V.I.N.CENT. runs into bedraggled fellow robot survivor B.O.B. (voiced by Slim Pickens, really) who reveals that Reinhardt’s robot servants are actually the animated corpses of the crew he claims to have sent to the escape pods 20 years ago, Mimieux’s father among them. Forster witnesses the necro-bot crew consign one of their own to the black hole with funereal ceremony.

When it’s revealed that Reinhardt has no intention of letting his guests leave alive, Perkins tries to go with him into the black hole, but is killed by Maximilian’s spinning immersion blender claws, howling as he falls dead. The last reel of the movie is a series of laser gun fights and escapes against increasingly dire sets and matte shots, the ship colliding with meteorites and tumbling into the singularity. V.I.N.CENT. has a struggle to the bloody death with Maximilian before sending his foe screaming into the void, and then watches as B.O.B. dies.

It should be said that if this sounds dark and epic, it kind of is, but it’s hamstrung significantly by some pretty wooden performances, as if the actors aren’t quite sure what sort of movie they’re in. All of it is scored by the Bond theme man himself, John Barry, and like the rest, it’ll give you tonal whiplash: The movie’s theme is paranoid and reeling and portentous, yet a couple fight scenes near the end are scored like campy space adventure.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-