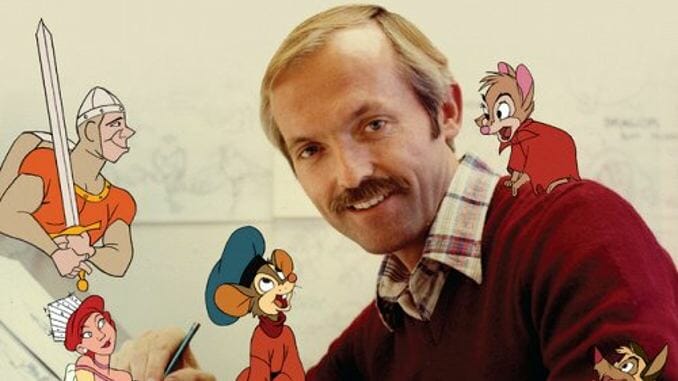

Somewhere Out There: My Animated Life Showcases Don Bluth’s Uncompromising Faith

When Disney is your competition, you can stay an underdog no matter how successful you get. Don Bluth, the animator and filmmaker behind movies like The Secret of NIMH, An American Tail and The Land Before Time, has seen his relationship with the House of Mouse go through a journey worthy of his on-screen heroes. A childhood spent in admiration, a youthful stint in its trenches, a journeyman’s alienation from its changing values, a master’s confident competition, a legend’s scabbed-over acceptance of defeat. In defining himself in relation to Walt Disney and his company, Bluth was and remains the ultimate David. In the face of such a corporate Goliath, it’s impossible not to be.

Bluth’s hardline stance on traditional hand-drawn animation only solidified his position as an industry oddity. Rare are Hollywood icons so artistically principled that they’d rather fail than change. Those values made Bluth into a martyr, a cult figure fighting the good fight with a fanbase fueled by nostalgia and respect. His new memoir, Somewhere Out There: My Animated Life, draws parallels between the faith-driven, uncompromising filmmaker and the entertainment industry at large with an uneven mix of personal detail and professional curtain-peeling—and refrains from putting him on the cross.

A devout Mormon, Bluth is noticeably hesitant to open up about his faith, even at 84. Perhaps there’s still a sense of shame surrounding his decision to leave Disney’s bullpen as a teenager in order to go on a missionary trip to Argentina. Perhaps there’s a deeper intimacy he feels protective of after a life unwittingly spent in the spotlight. Using both his faith and a “talking to my reflection” device to frame his inner fluctuations of pride and self-doubt, Bluth finally connects the dots between his deep religious roots, his art and his storytelling.

Of course his animal heroes reunite with family and with promised lands. Of course his tales favor the kind of clear-cut morality of fables and parables. It doesn’t absolve his movies of critiques that they can be derivative or overly simple, but it does explain why he might find that approach appealing beyond its formal familiarity. As Bluth constantly reminds us, he doesn’t take his faith lightly—be that praying at the altar of hand-drawn animation, or of the Latter-day Saints. He repeats the point so often and directly that it seems clear that he’s quietly needed to do the same to a secular Hollywood set for six decades. This self-deprecating seriousness reflects a sentiment running through his life.

Bluth went his whole career chasing the world-changing power wielded by Walt Disney. But coming in during the Golden Age of Animation’s decline left him adrift; he was weaned on and trained for traditional animation, finding his professional stride just as Disney died of lung cancer and the company began cutting corners. After working on films spanning Sleeping Beauty and The Fox and the Hound (with the aforementioned gap for proselytizing and earning his college degree), he saw the Nine Old Men losing power and their teachings losing sway over the next generation. He left Disney to strike out on his own because of a stubbornness backed up by faith—a dogmatic devotion to an art style and the (perhaps unfounded) belief that if they just stuck with it, they could brute-force their way out of the animation dark ages.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-