Eros

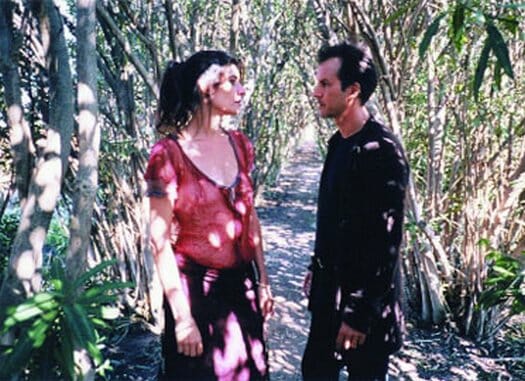

(Photo [L-R]: Regina Nemni and Christopher Buchholz in “The Dangerous Thread of Things.”)

It’s hard not to get excited about a single film by Wong Kar-Wai, Steven Soderbergh and Michaelangelo Antonioni, even though portmanteau films are usually disappointing. Part of the problem surely has to do with our own unreasonable expectations. We’d like three directors working independently to somehow discover the holy grail of interconnectedness. But maybe we should just be glad to see great filmmakers working in an unusual form and not ask for too much beyond that. Eros has a theme—sex—but it’s only skin deep.

The first film is Wong’s. It’s drawn from the same universe glimpsed in The Days of Being Wild and exquisitely realized in 2000’s In the Mood for Love. Entitled “The Hand,” it’s a visually moody piece about a woman who dallies with her shy tailor, complete with the perfectly timed tracking shots we’ve come to expect from Wong and his cinematographer Christopher Doyle. Once again they have the magic touch, but unfortunately so does the woman in the story. She lends her glove to the film’s title, and the film focuses too tightly on visceral, trite experience to be erotic.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-