Five Captivating Documentaries about Photographers

Both Helmut Newton and Robert Mapplethorpe—with their controversial nudes, their celebrity subjects and their undeniable artistry—helped transform photography into the in-demand, valuable medium that it is today.

By contrast, belovedNew York Times street photographer Bill Cunningham shunned the spotlight, as did Vivian Maier, whose extraordinary street photos only came to light after her death. And you might not have heard of portrait photographer Elsa Dorfman if not for Errol Morris’s documentary about her.

While the five documentaries that follow are a great place to start, we also recommend Agnes Varda’s Oscar-nominated Faces, Places and Annie Leibovitz: Life Through a Lens (directed by her sister, Barbara).

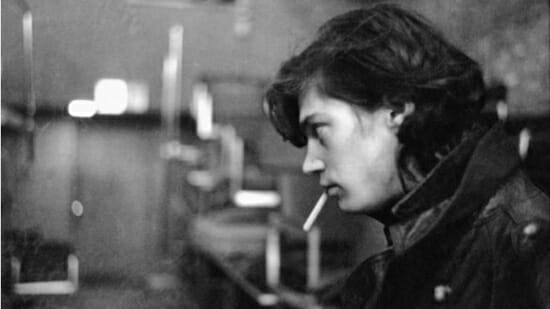

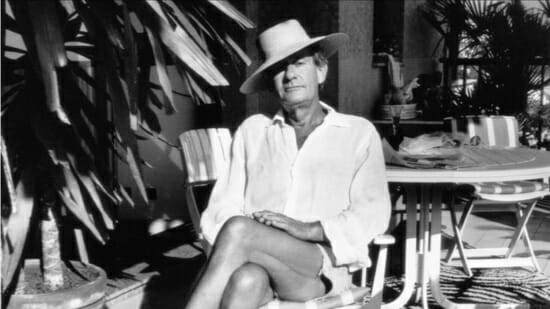

Helmut Newton: The Bad and the Beautiful (2020)

“He was a little bit of a pervert, but so am I, so that’s okay,” laughs Grace Jones, one of many of Newton’s subjects interviewed for Gero von Boehm’s documentary. Newton famously photographed her in a series of striking nude shots with then-boyfriend Dolph Lundgren.

Isabella Rossellini, whom Newton shot with David Lynch circa Blue Velvet, has a more nuanced take on the late German photographer, “He photographed women the way [Leni] Riefenstahl photographed men: There was something powerful and beautiful, but also frightening and repellent.”

Were Newton’s nudes empowering the women he photographed or was he simply objectifying them? One of his models says Helmut was holding a mirror up to society, “and there’s a lot of misogyny” to reflect.

Newton’s own take on his often controversial work: “I’m a professional voyeur. I have no interest at all in the people I photograph. The girls, their private life …. I’m interested in what I and my camera see. The outside. People tell me I don’t photograph the soul. I photograph a face, a body. The soul? I don’t get that.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-