Searching For My White Thunderbird: 50 Years of American Graffiti

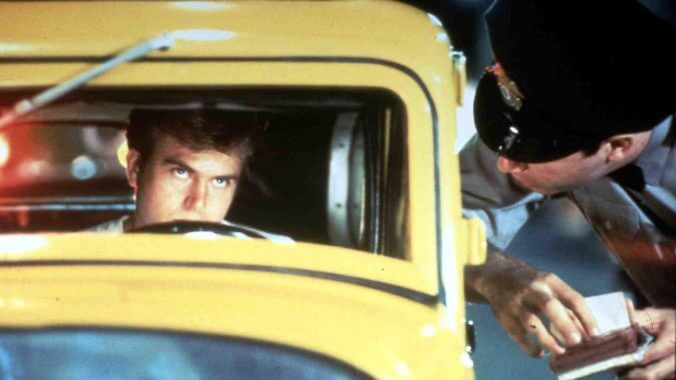

Photo by FilmPublicityArchive/United Archives via Getty Images

One summer many years ago, as firecrackers and bottle rockets painted the 4th of July air a technicolor flame outside our house, my dad ushered me into the living room and put his DVD of American Graffiti on the TV set. He said something along the lines of “I want to share this with you,” or at least that’s what I’ve chosen to remember him saying. I was maybe nine or 10, not yet aware of puberty’s massacre or high school’s plague of pimply-faced misanthropy. I was merely an overweight pre-tween who loved baseball, Superman-flavored ice cream, and rock ‘n’ roll. Life was euphoric, even if the country was in a recession and everything beyond the utopian, poster-filled walls of my shoebox-sized bedroom was, to put it frankly, fucked.

My dad has passed a lot of obsessions onto me: baseball cards, Motown, problematic comedies from the 1980s, the Bee Gees, Saturday Night Live, and the ever-agonizing destiny of loving Cleveland sports teams. But no gift has ever been as talismanic as American Graffiti, George Lucas’ second feature film—which was released in 1973, four years before he made Star Wars. It’s a coming-of-age film my dad, in no way, shape, or form, could actually relate to. It takes place in 1962—a full year before he was born—in Modesto, California—2,500 miles from Southington, Ohio, where he grew up. Yet, that wasn’t the point (it never is). The magic that exudes from every second of American Graffiti is what he latched onto—and it’s what I became obsessed with, too.

But the version of American Graffiti that has become canonized in my life is not the one that is canonized in my dad’s. He doesn’t acknowledge the existence of the sequel, More American Graffiti—which came out in 1979 and was massively panned by critics—but I do. He prefers to consider the picturesque perfection of the first movie and remain blissfully ignorant to the story’s forthcoming tragedy, but that’s too easy of a life to live. Perhaps it’s less of a burden for him to look at a pre-Vietnam War world and demand to live in it for as long as he possibly can (my dad’s formative years did hit just as the war reached a boiling point at the turn of the 1970s), or, perhaps, it is my own narrow-sighted opinion of what heartache and death and sickness really is that has rendered me forever desensitized to grief. It’s what allows me to enter the full world of American Graffiti rather than just its first chapter, but not all that glitters is gold.

American Graffiti is a 112-minute depiction of six friends’ last night of summer before Steve (Ron Howard) and Curt (Richard Dreyfuss) are set to head east for college. The way Lucas presents this solstice finale is eons different from the ones I lived through as a freshly graduated 18-year-old. There was no grand celebration of my final gasp of pre-undergrad freedom; only a high school romance ending in a driveway and a whole mess of anxiety about moving to a new place where I knew not a single soul. But that’s not to say that what American Graffiti offers its viewers isn’t what actually happened 60 years ago—especially in Southern California, which was always lightyears cooler than the rural Midwest.

At the end of American Graffiti, we learn a few truths about our four leading men: In 1964, Milner (Paul Le Mat) is killed by a drunk driver; in 1965, Toad (Charles Martin Smith) is reported missing in action while serving in Vietnam; in 1967, Steve is an insurance agent; Curt migrated to Canada and became a novelist. In More American Graffiti, those truths get fleshed out even more: Toad faked his death in order to escape combat, while Steve and Laurie’s marriage is spiraling as they navigate parenthood and sexism in suburbia.

What is most compelling about the story of American Graffiti, however, is the way in which the film (and its sequel) are eulogizing a moment we never actually see happen on-screen. Milner’s untimely death on New Year’s Eve in 1963 looms heavily on both movies, even if the event isn’t revealed until American Graffiti’s post-script and we only get to see him drive off into an empty highway he will never leave in More American Graffiti. Throughout the latter, we watch four friends navigate life after Milner’s passing while also watching his final day alive unfold. It’s one of the best uses of dramatic irony in all of cinema—and you can see so vividly how, even though our heroes no longer cross paths, they are bound together by Milner’s presence and, then, his untimely absence. I often consider how, beneath the gauzy, pretty surface of late-night West Coast pastorals and chart-topping doo-wop and rock tunes, there is a pretty stark and lonesome story of grief bubbling. Just as we are tasked with watching the joy of being a teenager in mid-century Modesto fade away through Milner’s point-of-view, we must later reckon with the heaviness of his passing through his friends who survived him.

Two years prior to making American Graffiti, Lucas made THX-1138—but the film failed to reach broader audiences, only bringing in $2.4 million at the box office. It was when Francis Ford Coppola dared Lucas to write a screenplay with a wider reach and more domestic appeal that American Graffiti was born—and Coppola would later serve as the movie’s producer. The blueprint that Lucas had created paved the way for films like Fast Times at Ridgemont High, Dazed and Confused and Almost Famous—films that examined teenagerdom through an emphasis on era-contingent music and the societal forecasts of young people at the time.

For American Graffiti, that theme centered around masculinity and the expectations that are thrown at 18-year-old men. Some folks argue that nothing happens in the film, but I argue that the it is one of the greatest depictions of three juxtaposing paths that confronted men at the time: Enlisting in suburban rebellion by never letting go of your youth, getting drafted into the soon-to-be Vietnam War, and the capitalistic pressures of finding a life’s purpose through a soul-sucking job. The entire central plotline of the film is about Curt considering what it would mean to not leave for college the next day, and he spends his final night in the Valley committing crimes with the Pharaohs, a gang of kids who ride around in a 1951 Mercury coupe. Milner, in particular, comments—multiple times—on the cruising strip’s march towards death. “The whole city’s shrinking,” he laments within the first 10 minutes of the film. The world around him is folding inwards, his peers are hightailing towards the coasts, and there he is, stuck drag-racing out-of-town chumps for an exhausted, fameless title.

What continues to define American Graffiti’s legacy is two-fold. One, the 40+ oldies that play on-screen make up, what is widely regarded as, one of the greatest film soundtracks of all-time. (The songs from Chuck Berry, The Platters, Fats Domino, The Skyliners, and countless others are still timeless.) Two, some of the biggest actors of the 1970s—Richard Dreyfuss, Ron Howard, Harrison Ford and Cindy Williams—flirted with stardom here in unparalleled ways. By the end of the decade, Dreyfuss would play a lead in Jaws and Close Encounters of the Third Kind and win an Oscar for The Goodbye Girl, Howard would get huge with Happy Days before transitioning to directorial work full-time, Williams would star in the Happy Days spin-off Laverne & Shirley, and Ford would assume the role of Han Solo in Star Wars.

Looking back, it’s unbelievable that the only proven actor of the bunch in 1973 was Howard, who’d played Opie Taylor for eight years on The Andy Griffith Show (Dreyfuss had one line in The Graduate in 1967, but not much else). But, then again, the practically unfamous cast of American Graffiti is what helps make the film so believable. Though nearly every main actor was older than the age of the character they were playing, their inexperience in front of a camera gave them a deftly uncanny rawness. It felt like we were watching teens come of age on-screen. The energy of the film was “you can’t stay 17 forever,” and each cast member was able to tap into that truth with such enduring potency. 50 years later, it’s still one of the best ensemble performances in movie history—and, possibly, the best smash hit to never win an Oscar (it was nominated for five of them, including Best Picture, but lost out to The Sting, among others).

From the very first frame of American Graffiti, when we are greeted by a shot of Mel’s Drive-In—referred to, affectionately, as Burger City in the movie—and Bill Haley & the Comets’ “Rock Around the Clock” rings out and the opening credit font is tricked out in neon signage, I could feel the magic of what was, to me, a bygone era. It’s important to understand what was happening in 1962: The Dodgers had only been in Los Angeles for four seasons, Beatlemania was still two years away, Kennedy was alive and in the White House, and Lawrence of Arabia was raking in millions. There’s also a great, generational dig at the burgeoning surf-rock craze of the time where, as a Beach Boys song plays on the radio, Milner tells Carol (Mackenzie Phillips) that rock ‘n’ roll has been falling apart ever since Buddy Holly died.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-