THX 1138 Is Actually George Lucas’ Best Film

The dystopian sci-fi tale turns 50.

George Lucas’ legacy is always going to be that he ushered in the age of the blockbuster with Star Wars, and it’s ironic when you consider that he very much saw himself as an outsider, a student of film and of storytelling who managed to make wildly successful films while butting up against studio heads. Now the formula he created is the dominant influence on American moviemaking: hot young stars in an adventure fantasy with tons of action scenes and special effects, telling serialized stories about coming to grips with destiny and fighting bad guys.

And yet, he’s largely vanished from Hollywood. Lucas has not directed a feature-length theatrical film since 2005. Since he sold the rights to the Star Wars universe, he has been mostly uninvolved in the phenomenon he created. He’s served as producer on a number of projects, but only a few have been feature-length films and none have reviewed all that well.

We think of Lucas—of all directors, really—as auteurs. We believe that they are the sole creative force behind the amazing stories that make it to the screen. This is not accurate, and Lucas’ fall from grace following the poorly received Star Wars prequels is sort of Exhibit A. The (out-of-proportion, infantile) disdain fans held for the prequels was rooted in a feeling of betrayal: How could the guy who gave us The Empire Strikes Back have also given us Jar Jar Binks and Chewbacca knowing Yoda? But lots of people gave us Star Wars. Lucas was just one among the (very important) handful of people that the first six films had in common.

THX 1138 isn’t solely a product of Lucas’ imagination, either. But when you hold it up against his other work—and it’s inevitable that you will—you see the kind of things that interested the young director from Modesto before he was famous, and the filmmaking techniques that eventually found their way into a galaxy far, far away. You see George Lucas the filmmaker, rather than George Lucas, the guy who invented Star Wars.

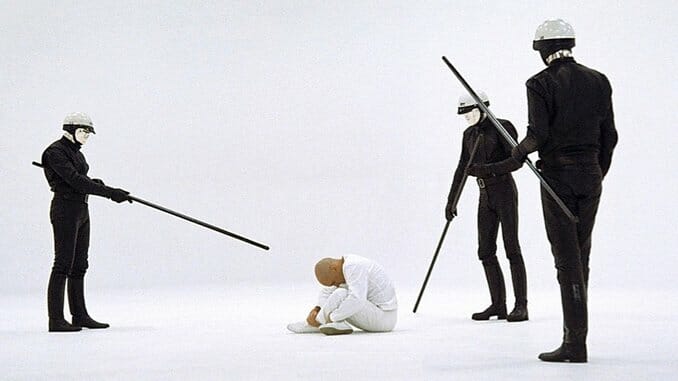

It is the distant future, though we don’t know when. (The 1967 short film that Lucas made while at the University of Southern California in which he set forth a sort of proof of concept for the movie is set in 2187. It was entitled, with his usual talent for the succinct, Electronic Labyrinth THX 1138 4EB.) The future is sterile and cruel. Individuality has been completely suppressed: Everybody wears blank white clothes and sports bald heads, lives in dark and unadorned homes with cohabitants they barely acknowledge, and goes to work in harsh industrial settings where hundreds of their fellow workers regularly die in nuclear meltdowns, all under the unblinking gaze of a ruthless surveillance state with a mechanized police force and a twisted synergy of consumerism and religion.

What must that be like?

The hapless THX 1138 (Robert Duvall), whose job seems to be carefully installing plutonium, is having a hard time coping with this dystopia. In a completely unintended parallel to our current lockdown, THX’s society is entirely underground, all on sickly lit indoor sets that look like they were scouted inside hospitals, factories, urban parking garages and malls. THX and his companion, LUH (Maggie McOmie), begin purposefully missing doses of their government-mandated sedatives and, horror of horrors, develop feelings for one another.

For this crime, they are separated and imprisoned. THX and the troublemaker SEN (Donald Pleasance, in a role as quirky as any of his most iconic) are herded into a bizarre prison, escaping back into a society on the hunt for them. THX manages to evade capture when his high speed car chase finally pushes law enforcement over budget, but we don’t get to see what sort of world his flight has delivered him to.

Here’s the thing. THX 1138 has nothing particularly new to say. Its authoritarian dystopia is of the kind you find in 1984 or Brave New World. Its story of a man seeking freedom beyond the stifling confines of society would have been familiar to moviegoers of 50 years ago, who were hitting theaters in the aftermath of the broken-down old Hollywood studio system to see films by young upstarts.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-