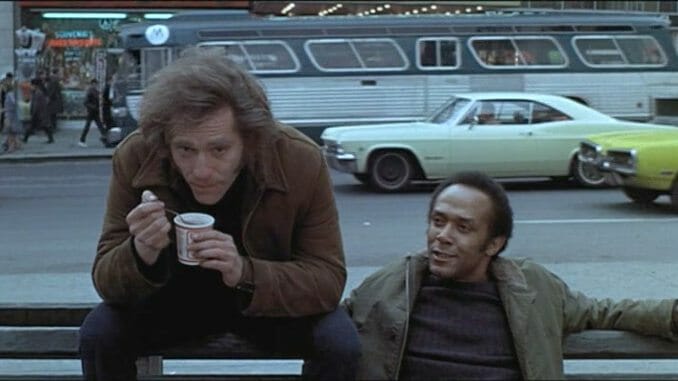

George Segal Gave One of the Great Unsung Performances of the ’70s in Born to Win

While George Segal, recently-departed mainstay of 1960s and 1970s Hollywood, was never exactly typecast—he played conmen and cops, drifters and businessmen, spies and soldiers—the men he embodied all shared a certain desperation. Nothing ever came easy to them. Like Nick in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? or Bill in California Split, they were often at the mercy of the stronger personalities with whom they kept company. Like Kelp in The Hot Rock or Charlie in The Duchess and The Dirtwater Fox, they had big ideas for themselves that far outpaced reality—often with perilous results.

Another factor that united Segal’s most memorable characters? Their charm. It was rarely a struggle for them to win someone over; one flash of that twinkly, aw-shucks grin could usually get them out of the stickiest situations.

Usually.

In Born to Win, J (Segal) is so charming, it seems entirely understandable that Parm (Karen Black) would fall for him as she amusedly observes him trying to steal her car.

“Would you like the key that starts the car, or would you prefer the challenge?”

“I’d prefer the challenge.”

She’s naïve when she meets J, noticing his “Born to Win” tattoo before she does his arm full of track marks, and then not quite sure what they are. Even when he comes clean about his habit, it’s not a deal-breaker for her. She takes him as he is, though she won’t stop trying to get him out of the city—because as J says, “It’s the environment that kills you.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-