Gleason

The best preparation for watching Gleason is to disabuse yourself of its inspirational marketing. This is true even if you don’t care for football as sport or entertainment, or if you have miraculously found a way to insulate yourself from absorbing football scuttlebutt via pop culture osmosis. You might think about Wiki-researching the film’s star, Steve Gleason, the former New Orleans Saints defensive back who wrote himself into legend in 2006 with a single blocked punt, but why bother? The film does an exemplary job familiarizing the uninitiated with Gleason’s career accomplishments and personality within its first 20 minutes before shifting toward 2011, the year he was diagnosed with ALS.

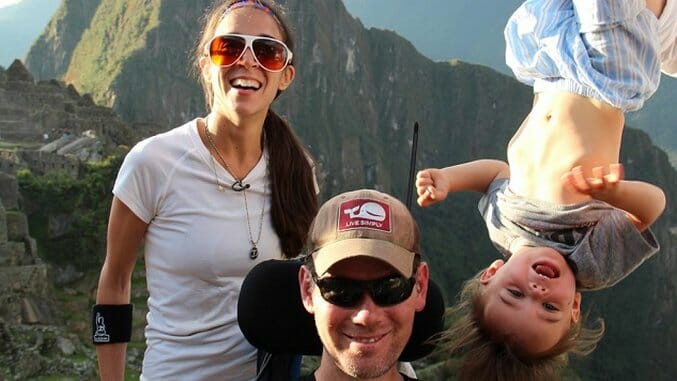

Gird yourself for an emotional shellacking, for all the good that’ll do. It would be wrong to say that Gleason isn’t, in its own way, inspiring, or celebratory, or encouraging, or any number of positive adjectives that convey “triumph.” As the film moves forward, moment by moment, through Gleason’s struggles with ALS, there are heartening, tender and on occasion very funny beats that make Gleason, his wife, Michel Varisco, their friends, their family and the production crew look equally as relentless as his condition. For every push the disease makes in ravaging Gleason’s body, they push back. It helps that Gleason finds purpose by recording video diaries for his and Michel’s unborn son, his way of sharing as much of himself with the child as possible while he’s physically able to.

But when you commit to having your life with ALS captured on camera, you commit to being seen at your lowest points, and at points lower than that. Gleason never shies away from reality, and that’s a big component of what makes it great. It’s an even bigger component of what makes the experience of watching the movie so soul-shattering, and by extension is the precise reason why walking into the theater with the phrase “inspirational sports doc” in your head will set you up for a sucker punch. Primarily, Gleason is not an inspiring film. It is a harrowing one. It is a two-hour chronicle of how terminal illness consumes its victims and overwhelms their loved ones, a portrait of what it is like to be helpless, in visceral terms, to your own mortality, and what it is like to watch the person you care about most in the entire world die slowly while you can only stand and watch.

Gleason has its heroes, of course, and they perform what can only be considered heroic feats under the film’s circumstances: The birth of both the Gleason Initiative Foundation and the Steve Gleason Act are notable hallmarks, to say nothing of what Steve’s custodians do simply to get him through the day. Steve himself is a force of astounding vitality, while Michel gives all of herself to support him and, eventually, raise their baby boy, Rivers, whose emergence 40 minutes into the film is like watching a match light up darkness. Michel does the lion’s share of the work in the foreground; she shaves Steve’s face, clips his toenails, feeds him with one hand and Rivers with the other, assists in administering enemas (though not necessarily in that order). Her responsibilities are endless, and she shoulders them with determination.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-