Terrence Howard and Cuba Gooding Jr. Cash Their Checks for Dire Horror Skeletons in the Closet

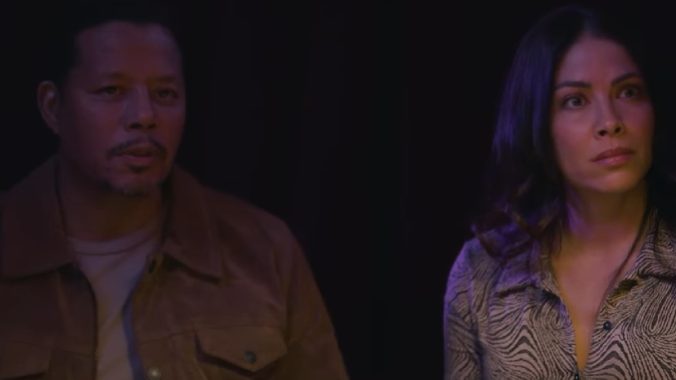

Neither Terrence Howard’s nor Cuba Gooding Jr.’s star power is near dazzling enough to salvage the nondescript supernatural horror story Skeletons in the Closet. Director Asif Akbar is a prolific indie filmmaker whose low-budget films (somehow) hook names like Tobin Bell and Randy Couture, but it’s quantity over quality. The executive producer of Amityville Shark House brings little prestige to Skeletons in the Closet beyond a one-and-done Marvel star and an ex-Oscar winner who was probably just shown the money, letting special effects unfit for ’90s basic cable be as good as it gets. Akbar’s ghostly Las Vegas tale lacks soul, polish and authenticity, which becomes apparent in record time as Howard narrates over a cheapo opening credits sequence of smoke overlays and a freshly downloaded Halloween font package.

Writers Koji Steven Sakai and Joshua A. Cohen establish a rather unenthusiastic and needlessly complicated story about demons, tarot readers and broken families. Howard stars as Mark, a husband and father doing all he can for his loved ones, whom we meet the day he’s fired from whatever job he thought would give him a raise. To make matters worse, his daughter Jenny’s (Appy Pratt) brain cancer has returned, and treatment cannot begin until someone foots the $50,000 bill. Mark turns to his once-incarcerated brother Andres (Cuba Gooding Jr.) and throws himself to ruthless loan sharks—but there’s more conflict afoot. Mark’s spooked wife, Valentina (Valery M. Ortiz), starts seeing visions of a squealing apparition with unknown motivations, adding “a possible demonic tether” to their problems.

It’s all, quite bluntly, a mess. Producer Al Bravo notches a story credit, while Terrence Howard and on-off partner Mira Pak Howard claim screenplay credits in some capacity, creating a distinct “too many cooks” discombobulation. Skeletons in the Closet isn’t very descriptive with its lore until it buries you in exposition, failing to establish proper backstories that feed into shady underground deals or the purgatorial plane of existence inhabited by ominous mystic Luc (Udo Kier, an ominous mystic).

Akbar relies on stereotypical representations of black magic and spiritual elements—a snake around Kier’s neck, random cuts to a figurine of Saint Death—but struggles to connect the plot’s scattered dots. It’s not a difficult story to follow, but Akbar’s delivery trips over itself by jumping from boilerplate haunting beats to rejected Sopranos goons to the stuffy Hallmark drama of Jenny’s illness. And Akbar produces no style or substance to speak of as a director.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-