Life or Something Like it

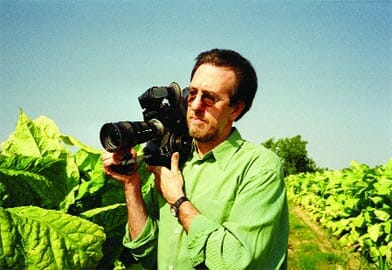

Before Morgan Spurlock’s Super Size Me, Nathaniel Kahn’s My Architect and Jonathan Caouette’s Tarnation, there was Ross McElwee. The father of the first-person documentary has been making films since the late ’70s, his most famous work being the 1986 feature Sherman’s March. His latest movie, Bright Leaves, is a gorgeous return to his native South.

“I had an idea for a long time that, since I’m from North Carolina, I should make a film that deals with tobacco,” says McElwee. “But I also knew that I didn’t want to do a standard condemnation of the tobacco industry. It’s been done. I wanted something different. A cousin reminded me that a great grandfather [of ours] was involved in the tobacco industry. Then a second cousin told me that yet another cousin, John McElwee, had some kinds of pictures that had something to do with my great grandfather.” It turned out that Ross’ cousin John didn’t just have pictures, he had a whole movie—a Hollywood melodrama called Bright Leaf that starred Gary Cooper and seemed based on the life of their great grandfather. “I thought, ‘This is too much. This is the door I’ve been looking for. This is how I’m going to make my movie about tobacco.’”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-