Making a Mann: Revisiting Michael Mann’s Feature Debut, The Jericho Mile

To many, Michael Mann “debuted” in 1981 with the sleek, stylish, synthy and oh-so-80s crime thriller Thief. It’s an auteurist’s perfect first feature, after all, with a director storming through the theatrical gates with a fully realized aesthetic, politics and film form. It’s also, of course, not Mann’s first movie, just the first that wasn’t made for TV. With 45 years of hindsight on Mann’s perfectionist oeuvre, The Jericho Mile can at first look like a trial run for his career in the same way that L.A. Takedown was a trial run for Heat. But that would be doing Mann—a constantly resourceful, reactive and iterative artist—a disservice in favor of a neat mythos. While The Jericho Mile is indeed a prologue to his more canonical oeuvre, it is also the end of the journey that made him Michael Mann. Before Mann could really express his native Chicago on screen, he first had to find his voice.

Mann wandered to Wisconsin and London for school, and as a student found himself interviewing aspirational revolutionaries in Paris in May ‘68. Not long later, he filmed a road trip from his home city to California, where he saw the hippie peace movement come into conflict with deeper racial tensions in the United States; as an aside, both of these films are, for various reasons, unlikely to be seen again publicly, although some riot footage from the latter appears in Mann’s Ali.

Mann’s literal journey down to Hollywood was also a spiritual one as he cut his teeth throughout the ‘70s, primarily writing for TV. Midway through the decade, Mann found himself working on one of the foundational projects of his career, one that he would ultimately not be credited for: Writing a feature adaptation for Edward Bunker’s seminal first novel No Beast So Fierce. Initially, Dustin Hoffman was directing the film on top of starring in it, and according to Mann, had started production inside Folsom Prison before Hoffman decided he couldn’t direct it. Ulu Grosbard took over, and what would become the movie Straight Time started to move away from Mann’s script.

Mann describes No Beast So Fierce as “probably the best American prison novel,” although Bunker himself didn’t agree. “I wouldn’t call it either a prison novel or a prison film,” Bunker told Brooklyn Rail. Instead Bunker saw the work as about how prison affects a person mentally. And indeed, there’s only a couple dozen pages of literal incarceration in Bunker’s 300-page novel. Much more of it is focused on the psychological realities of someone who spent so much of their life behind bars trying to navigate the world outside—one as systemically against them as it was before they got released.

The arc of the book takes its protagonist Max Dembo from the gritty realism of street-side hustling and the clinically evil bureaucracy of parole officers to an operatic, globe-spanning finale following a massive robbery-turned-shootout with LAPD. The choice between turning a chance romance into something real at the risk of being locked up versus an ideological commitment to escape, which wrestles inside Dembo’s character, seems like a template for Neil McCauley in Heat. Mann revisiting Chris Shiherlis’ restlessness in Heat 2 continues in this same vein (not to mention, Jon Voight’s character Nate is literally modeled after Bunker). Suffice it to say, No Beast So Fierce has stuck with Mann for almost half a century. And it’s that opening dozen or so pages that Mann worked to extract first—Straight Time might’ve left the Folsom of the novel behind, but Mann wanted to get in.

“The first time I was in Folsom [for The Jericho Mile], my expectations of what prison would be like were totally wrong,” Mann explains. “I thought it would be an oppressive situation; that meant the men would be oppressed by a system of guards and it was exactly the opposite. The guards were scared to death of the convicts. They were basically hiding in the guntower.”

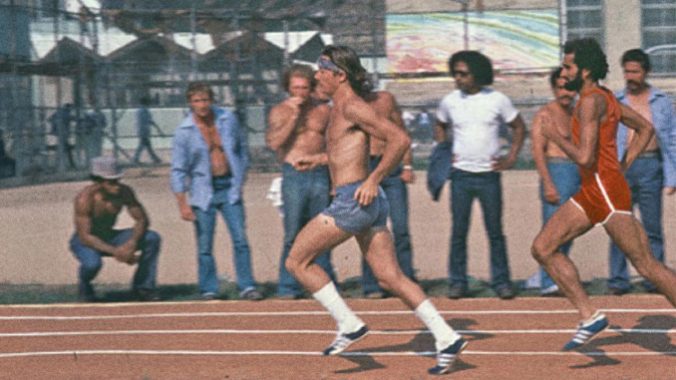

What Mann found in Folsom were what he described as “mature” inmates, ones who had gone to prison, got out and got committed again, got shipped off to San Quentin before they failed out of there too. Folsom was the end of the line. In these confines, the men knew how to build their own structures of power within the walls and false realities to keep their minds from wandering towards thoughts of the life they might be missing out on. For The Jericho Mile’s Larry Murphy (Peter Strauss), the way to hide is not in his head but his legs—he runs himself to exhaustion every day before he gets a chance to think.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-