“Arty” Is Rad: Mike Mills on C’mon C’mon, Joaquin Phoenix and the French New Wave

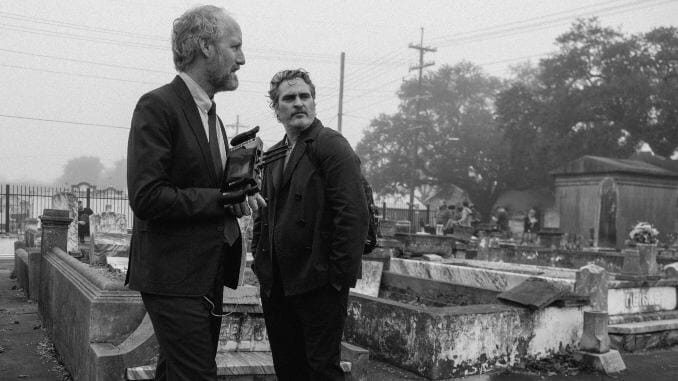

Twenty-two years and four features into his filmmaking career (not to mention an impressive music video oeuvre that ranges from Yoko Ono to The National), writer/director Mike Mills has built his name on a particular style of gentle, introspective storytelling. In conversation, he comes across more like a therapist than anything, proving tyrannical demeanor an unnecessary ingredient in the stew of creative genius. His newest film, C’mon C’mon, marks a tonal pivot for its co-lead Joaquin Phoenix—whose last performance in Joker earned him a little gold man—but it fits cleanly into Mills’ creative fold, even if it brought new challenges.

The tender, galvanizing film follows a traveling Ira Glass-esque radio show host named Johnny (Phoenix) and his young tag-along nephew Jesse (Woody Norman). Jesse’s mom Viv (Gaby Hoffmann) is busy helping her addled husband (Scoot McNairy) break addiction in rehab, and she has no choice but to call her childless brother in for parenting reinforcements despite his lack of experience.

Guiding viewers through the movie with his trademark openness and honesty, Mills takes a perspective that makes sad realities simply seem like new realities that take some getting used to. He leaves space for melancholy and ecstasy in equal measure, offering viewers a breath of fresh air in the relatability of it all. On the eve of its theatrical release, Paste hopped on a video call with the director to talk about the nature of his work, his collaborators, and the narrative and stylistic choices that set C’mon C’mon apart in his filmography.

Paste: All of your features are about parents and their children from one angle or another. C’mon C’mon is that, but it’s also a bit of a twist on that. Why are you drawn to that kind of story?

Mike Mills: I guess I love therapy [laughs]. That’s what you talk about in therapy all the time, right? Well, first of all, to me it’s really important not to just say “family.” Cause it sounds so biological and heteronormative and all that stuff, and families are just primary relationships, really—people who show up. I think all of my films have had a bit of an alternative family situation going on. And I feel like it’s that interpersonal terrain. You figure out yourself and who you are in relationship to other people. And you’re kind of different with different people and it’s how we figure out the rest of life. I feel like I’m just going to the core of how we figure out our lives. And all the stuff that happens…it’s a very complicated space. To me, it’s very Game of Thrones space. Everything intense actually happens in that space and in those kinds of relationships. And I don’t know, I would say it’s what I’m just super drawn to—to find the most expansive, nutritious, informative, dangerous, fun, funny, sad space. I like it a lot.

Why did you go the uncle/nephew route this time?

Mills: So this came from me and my kid. That was the seed, the beginning. And it’s the first time I’ve dealt with a story that starts with a real, living person and a younger person. So I feel very responsible about protecting my kid and our privacy, and I didn’t know how to make the film for a very long time because of that. I just couldn’t figure a way in. And it was just slow pieces. “Well, if I do this, if I do that, if I do this, if I don’t say this and I say this.” Then, I have an alleyway I feel comfortable with. One of them was separating it from me and my kid by making him an uncle, but then that did all these other things I didn’t intend. I was like, “Oh rad, if he’s an uncle that’s never had a kid before, he has to learn parenting in every single scene.” That’s Buster Keaton filmmaking. That’s great. And it has all the condensation of experience that a film really needs, as someone who just doesn’t know what they’re doing.

But then the other weird thing, that I can’t even really explain, is that when I was writing that out I was like, “This actually just feels like what I feel like as a biological father.” You constantly don’t know what you’re doing, constantly getting to the edge of your ability and going further. And your kid’s constantly changing. Every six weeks, or maybe two months, or three weeks, they change! And they change the rules and their operating systems, and you have to relearn your kid. So, actually, it felt really accurate to describing my dad experience.

Your films have a therapeutic, pastoral quality to them. There’s something about them that feels like we’re witnessing real life through the lens of the spirit or the interior. And there’s a preciousness about life to them—but one that allows us to eventually let go and live, one that makes us feel calmer and better about being. Is that hope something you’re actively trying to create, or is it just organic in your work?

Mills: Hm, well, I don’t think of it that way. That would be kind of presumptuous for me to think like, “I’m gonna comfort people!” [Laughs] I don’t know. But, but! I think the honest answer is: So, I deal in my life with not serious depression, but kind of chronic mid-low-level depression. Or, I can get down. I can get Eeyore quite easily. And if I’m going to spend five years making something, I need to buoy myself. I need to find ways to engage with life, to find something hopeful, to find something connective and kind of growing and positive. That’s part of the goal for the whole project: To keep me from sinking. Or feeling so alienated that I feel inert. Or so impossible to be myself just because of me. Not because of anything anyone else did, but that I can’t operate in the world, right? I think all my films are talking to that. That’s part of what they’re doing. They’re loosening up that part [motions to brain].

I often think of Michael Haneke. That dude must be really fucking happy [laughs], or really strong, or have a fucking good sense of health. Cause if I made those movies, I would off myself. I would be afraid of what would happen to me. And, obviously, everyone has a way of helping themselves, if you think about it. Some people love snuggles and some people love BDSM, and each one is completely valid and completely strong and completely subversive and completely powerful. If Michael Haneke made my movies, he probably would kill himself [laughs].

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-