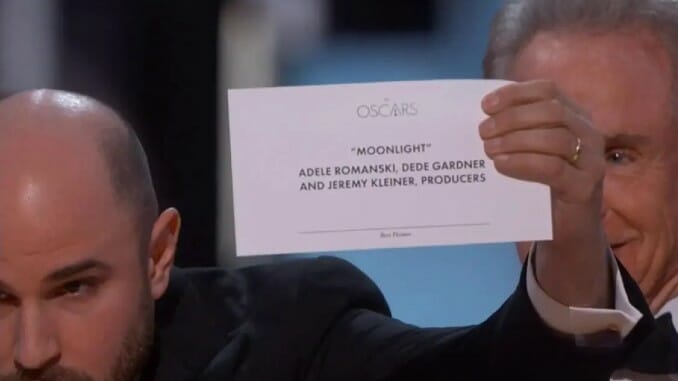

It’s the 2017 Academy Awards. There’s only one award left, the big one. And while everyone holds their breath, there are only two possible winners: The flashy and sentimental Hollywood tribute musical La La Land and the intimate and daring indie drama Moonlight.

It’s hard to remember the insanity of watching that moment live. It produced a greater reaction than any snub or surprise. Memes of the envelope being revealed covered the internet for weeks. It was a mistake we didn’t want to let go of. But five years later, that one mistake has left a disappointing legacy. La La Land and Moonlight will never be able to be appreciated for the movies they are without being tied to that one moment and each other. And as the Oscars struggle to retain viewership, the moment has become its last hurrah of relevance, albeit in an embarrassing manner. In a story of the past never letting go, the starring roles are two very different films and the setting is one very dated institution.

I. Our Villain: La La Land

If there was ever a movie that could be called Oscar bait, it’s La La Land. The film, inspired by the Golden Age of Hollywood musicals and the relentless optimism of people trying to make it in the business, ticked every box an Oscar hopeful could have. It’s nostalgic, it’s colorful, it’s sentimental, it’s a movie about movies, it stars young Hollywood darlings, and it upholds that striving for your art is the greatest and most painful cause imaginable.

La La Land has soured over the years. The easy target is Ryan Gosling’s Sebastian, an aspiring jazz pianist stuck making commercial and “soulless” music. Rewatching the movie, his scenes where he explains the heart of jazz to a disinterested Emma Stone are the worst of the film, and his character lacks the charm that would be the only way to stay with someone that insufferable.

But the criticism of La La Land has stuck in the past half decade. It’s more common to see it described as corny, uninspired, only a façade of something that has something meaningful to say. The dancing and musical elements have come under greater fire for their boring composition and choreography, especially compared to the musicals La La Land is inspired by like Singing in the Rain and 42nd Street. Even Emma Stone’s Oscar-winning performance has cooled in the public’s eye (while she was the favorite to win, she was up against Isabelle Huppert’s captivating performance in Elle, one of the greatest performances of the 21st century).

With the current dislike of La La Land being so prevalent, it’s hard to remember how beloved the movie was when it first came out. Of course, many criticized it from the start, but there was an optimistic fervor when it came out. People raved about its beauty and genius, and it was one of the rare popular movie musicals. The movie made nearly $450M worldwide, and theaters near me were still full weeks after its release. It felt like the type of movie that only came once in a while, something that was unafraid in its love and sentiment. As Owen Gleiberman put in his review for Variety, “[La La Land] lifts the audience into a state of old-movie exaltation, leading us to think, ‘What a glorious feeling. I’m happy again.’” If you still believed in the magic of Hollywood, it grabbed your heart and wouldn’t let go.

But some of the lasting criticism of La La Land seems to be rooted in the 2017 flub. While some hated it from the start, after that moment no one wanted to lend the film any kindness. La La Land became the villain, the usurper that tried to steal the award away. La La Land is symbolic of a film that just assumes it will receive praise through its subject matter. In an era where we have become more critical of movies rooted solely in nostalgic inspiration that don’t seem to innovate beyond that premise, La La Land was a big-budget Hollywood film that didn’t push the status quo even an inch. No one wanted to stand up for the “white guy explains jazz” movie. It was the film with every advantage, and it still took the spotlight in what should’ve been a groundbreaking moment for someone else. After the 2017 flub, it wasn’t enough to dislike La La Land or let it fall into obscurity—it became a film that people kept going back to, each time with a more critical eye, each time sinking the film’s reputation deeper.

And yet, La La Land refuses to die. The score continues to be popular (several of its songs have had shining moments on TikTok) and people who see Hollywood through rose-tinted glasses or are hopelessly romantic at heart continue to be enamored with its vision of Los Angeles and love. But when these positives come up, criticism is always close to follow. We can never let La La Land forget what it did to Moonlight.

II. Our Tragic Hero: Moonlight

Moonlight was everyone’s favorite underdog. With only one other film under his belt, writer/director Barry Jenkins broke onto the scene with his touching coming-of-age drama about a Black man growing up, struggling with his identity and sexuality. The praise was universal; Moonlight quickly became the “movie you need to see” of 2016.

There is a perception around the Academy Awards that emotional films about underrepresented minorities are shoo-ins to win big prizes. But looking at the history of the institution only proves the opposite. Especially when it comes to movies centering LGBTQ+ people and their stories, very few break through to the actual ceremony. For every Milk, there is a Brokeback Mountain, a film that was relentlessly and homophobically made fun of for its “sad gay cowboy” image back in 2003. The Academy—and studios—are still afraid to put money and confidence behind daring films about queer people.

So when Moonlight, a film that centers both race and sexuality, started picking up significant awards traction, there was a hope that this may be one of the most deserved Oscar wins in recent history. But after the 2017 flub, even once those statutes were put in the correct hands, Moonlight never got the legacy it deserved. The film is forever tied to that mistake and to another film that didn’t win. Its Oscar win boosted the film’s viewership, and I don’t doubt the mistake increased interest in Moonlight even more, but Moonlight can’t shake how it won its award and the fanfare around it.

I still don’t think Moonlight is getting the retrospective evaluation it should, and it might not for a long time. People know Moonlight is brilliant, but compared to the fervor with which people still talk about movies like Lady Bird or Hereditary, people seem comfortable relegating Moonlight to the past. Perhaps the subject matter is more difficult to bring up casually, but I still see new takes on La La Land—and even Jenkins’ 2018 film If Beale Street Could Talk recently received a revival of interest on TikTok. Upon rewatches, Moonlight is still irresistibly fresh and gorgeous, a movie worthy of the careers it boosted: Barry Jenkins, Mahershala Ali—even Nicholas Britell (would we have the Succession theme song without Moonlight?).

Moonlight got its big moment stolen for a reason completely out of its control. The emotional impact was diminished by everyone still being in shock that such a mistake even happened. But while La La Land has endured as a subject of critical evaluation and a film that prompts continued interest, Moonlight is still a tougher and more complex film that struggles to be celebrated in the way it deserves. We have taken for granted how improbable it is that it won Best Picture. The movie’s legacy will always be shared with Jordan Horowitz’s hand and an envelope reading its name.

At the recently opened Academy Museum of Motion Pictures, there is a small room dedicated to the Oscars ceremony and notable moments from its history. Tucked away in a corner is that very Best Picture envelope, next to a letter written by Warren Beatty to Barry Jenkins. It reads: “Congratulations. It’s much deserved.” Beatty’s message is sweet, but not complete. Moonlight deserved better than the win it got.

III. The Setting: The Academy Awards

The Academy Awards are like the English royal family: They only work if you believe in their power. The opulence of the ceremony and the continued tradition of ballot-guessing is only entertaining if you have decided to believe in the Oscars’ constructed reality. The 2017 awards were the 89th ceremony and marked a turning point for the institution. After two years of all-white Oscar acting nominees and the birth of the #OscarsSoWhite movement that expanded diversity in the Academy, the Oscars were being primed to become a more modern institution. But the 2017 ceremony still posed a problem for the future of the awards show: If its most exciting moment in years came from a mistake, how can the Academy Awards make it through the century?

A positive to the debacle could be that Moonlight opened the doors for more groundbreaking films to get their due at the Oscars. But just two years after Moonlight’s win, Best Picture went to Green Book, a dull and regressive take on race relations (although Ali did get another win). Nomadland is another quiet drama that took home the top prize, but while its naturalistic filmmaking is a change of pace for the Oscars the actual subject matter, dealing with poverty and age, did not feel like new territory compared to Moonlight.

If the Oscars are going in any new direction, it’s toward the rest of the world. Parasite’s revolutionary win and Drive My Car’s recent Best Picture nomination show a trend toward integrating international cinema into Hollywood prestige. As filmmaking becomes a more global enterprise, it’s harder to ignore the quality of films being made outside the U.S.

But after the 2021 ceremony, it’s clear the Academy Awards have clearly not learned their lesson. Expecting a posthumous win for Chadwick Boseman, the producers decided to rearrange the categories, putting the traditionally penultimate Best Director in the middle and Best Picture second to last. This disservice led to Chloe Zhao’s win for Best Director, making her the first woman of color ever to win, being undercut all in the name of a big emotional moment that never came to be. In trying to be important, the 2021 Oscars diminished the most important moment of the show. Just this week, the Oscars’ mission to regain relevance has taken more victims. The announcement came that eight categories (Best Makeup and Hairstyling, Editing, Score, Production Design, Live Action Short, Documentary Short, Animated Short and Sound) would be cut from the live broadcast and instead be pre-recorded to be added in later. This offensive disservice to these categories shows a complete disregard for the people who make the movies the Oscars claim they want to celebrate. The Oscars are chasing after an impossible audience, and in the process alienating the few people that enjoy the show (one of them being myself). The Oscars can’t stop shooting itself in its golden foot in its pursuit of a “perfect” show, because it’s become clear they don’t actually care about celebrating films—they just want eyeballs.

IV. A Pessimistic Conclusion

When the decade ended, many looked back to the best movies the 2010s had to offer, or began to predict the films that would endure in history. Moonlight was included on most of these lists, and even La La Land got some honorable mentions. The Academy Awards often celebrates good films that become lost to time, but these two have hung around as some of the best the 2010s had to offer. Despite its faults, La La Land is still refreshing in its optimism, and I find something wonderful about loving a dream without cynicism. Moonlight is sadly already fading in film discussions, relegated to a film that we all accept as being good, but don’t feel the need to bring up in conversation or elaborate on. It should endure as more than a subject of academic inquiry, as a brilliant piece of art that we seem to have taken for granted, a film that still feels as special as it did on the first watch.

La La Land and Moonlight are two of the best popular films of the 21st century. An intimate exploration of one individual’s race and sexuality made $70M; a nostalgic musical caught the public’s attention and still has it. These are films that deserve to be thought of as special, as distinct, as the rare occasions where quality is rewarded at the Oscars.

So, what are we left with? An embarrassing moment, a dying award show and two films that will forever be connected by a silly mistake out of their control. For every silver lining in the situation there is still a feeling of the moments we lost, of the legacies that will never come to be.

The Oscars face a very difficult challenge in the coming years. People are becoming tired of the show, and the show is grasping and failing to maintain itself. The move toward international film is a good instinct, but the Academy Awards have much more work to do than just celebrating films from more locations and filmmakers. Cutting out key categories is a bad sign that the show has completely lost its way in its pursuit of popularity. Part of me fears that in the years to come, more mistakes will be made as the institution tries to innovate its way back to the status it once had. I just hope that it won’t take down the films it tries to celebrate along with it.

Leila Jordan is a writer and former jigsaw puzzle world record holder. To talk about all things movies, TV, and useless trivia you can find her @galaxyleila