My Architect: A Son’s Journey

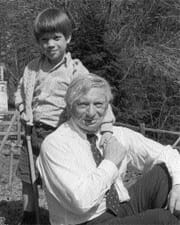

In The Ballad of Ramblin’ Jack, a documentary released in 2000, Aiyana Elliott tells the life story of her folk-singing father, Jack Elliott. When she wishes aloud that her father had done more parenting than rambling, the musicians from Jack’s past say, well, yes but then we wouldn’t have the music of Ramblin’ Jack and might not have the music of Bob Dylan. In My Architect, Nathaniel Kahn seems to be searching for someone who’ll say something similar about his father, architect Louis Kahn, but the hypothetical scenario is more complex in Kahn’s tale. As an illegitimate child, he wouldn’t exist if his father had been a more traditional family man. Lou, as his son calls him, was an architect who slept on a roll of carpet in his office, easily lost track of whether it was night or day and juggled three simultaneous families, with at least a child each. The first time Lou’s progeny met was at his funeral in 1974.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-