My Life as a Zucchini

My Life as a Zucchini begins bleakly. Our nine-year-old, blue-haired protagonist (voiced by Gaspard Schlatter) is called Icare—translated in English as “Icarus,” though the allusion hardly seems to matter—but he insists on going by Courgette (“Zucchini”), not because he looks like a vegetable or because a zucchini has any metaphorical relevance, but because it’s a nickname his mother gave him. And within those opening minutes, Zucchini has every reason to cling to a small gift from his mom: The boy, completely by accident, kills her. Nowadays, this is just how Oscar nominated kids movies do.

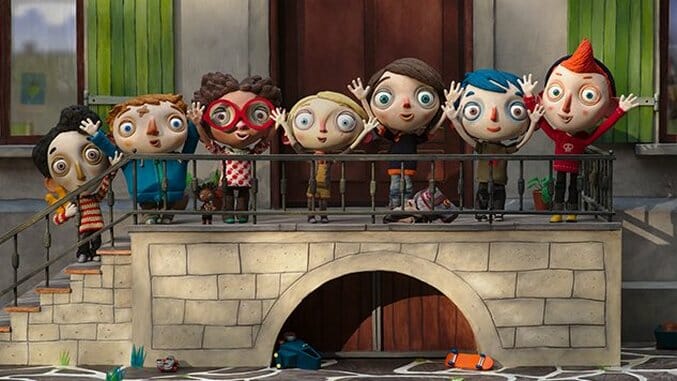

From there, the film lightens considerably, even though Zucchini, orphaned post-accident, meets a cadre of broken children at the orphanage to which he’s assigned. After winning the begrudging respect of Simon (Paulin Jaccoud), the self-appointed leader of the small group of castaways, Zucchini learns of the plights of his fellow children: abuse, pedophilia, severe mental illness, alcoholism—all of this Simon relates with little understanding, besides that for each child an unthinkable tragedy means there is no one left to love them, and thus they end up there, bound by their foster-less-ness.

Which of course doesn’t seem less bleak than the film’s opening matricide, however unintended, but director Claude Barras never strays from the perspective of the shy, perpetually overwhelmed Zucchini, and so even in the depths of despair, Zucchini’s world is a tactilely warm and rosy place. It helps that Raymond (Michel Vuillermoz), a police officer who becomes immediately smitten with the quiet boy, visits Zucchini often, and that the orphanage is a genuinely loving facility, as close as any of these kids have to a stable home. Barras seems wholly unconcerned with the kind of bureaucracy and lack of funding that typically plague such social service institutions, instead set on creating as optimistic a movie as he can despite the pall of dread that seems to hang over these kids’ lives. Perhaps we’re conditioned to expect the worst with stories such as this, so we anticipate something horrible to happen to disrupt the careful lives these children have built for themselves—and (spoiler?) nothing ever does.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-