Narco Cultura

When Michael Moore indicted America’s gun lust for its role in school shootings in his film, Bowling for Columbine, his work was decried as “un-American.” Israeli photographer-turned-director Shaul Schwarz is an outsider looking in on the mass cultural appeal of violence in Mexico as the drug wars continue to destroy family and communities.

As if that wasn’t already bleak enough, Narco Cultura starts its exploration by overseeing a scene that has become all too familiar: groups of kids gossiping about the murder they just witnessed, cops with masks pushing onlookers away, their work punctured by the unearthly wails of relatives held back by neighbors from the bodies of their loved ones. When the title fills the majority of a blacked-out cityscape, only a bloodied body and the attending officer’s legs are lit.

That is when we meet our guide to the battleground of Juarez, Juan Luis. A life-long resident, he recounts the drug war’s push to the border as he drives along vacant city streets and shuttered businesses that couldn’t afford extortion money. In 2007, there were 320 homicides in the metropolitan city, he tells the camera. Three years later, 3,622 lives were lost in 12 months. The drug war had mercilessly arrived.

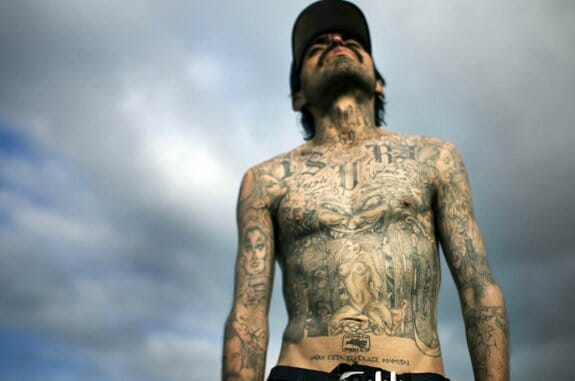

Across the border in Los Angeles, a young musician is busy recording a theme song for a drug lord. The music he and his band specialize in is known as corridor alterado, part of the Movimiento Alterado (“altered movement”) culture of art, music, and movies that deify Mexican drug lords and the violence that comes with them. While outlawed in Mexico, Movimiento Alterado is gaining popularity with characters like El Komander and the young corrido band introduced on tour, BuKnas. The movement has also spilled into exploitation-like movies about gunslingers and drug runners.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-