Once Upon a Time in the West at 50

“Several great directors of Westerns came from Europe: Ford is Irish, Zinnemann Austrian, Wyler is from Alsace; Tourneur, French. I don’t see why an Italian should not be added to the bunch.” —Sergio Leone, quoted in his biography Once Upon a Time in Italy

A lot of subgenres are particular to their culture of origin, but the Spaghetti Western was international right from its birth. Sergio Leone (about whose lifelong interests in macho Americana I’ve written about in reference to another genre milestone) gave birth to that subgenre using American stars, Italian bit players and crew, all while filming in the Spanish desert. Faced with the peculiar artistic adversity posed by this babel of foreign collaborators, he kept dialogue spare and focused on sweeping operatic staging and focusing on emotions.

While Leone was not the first Italian director to tackle the Western, he codified the tropes and conventions we now associate with the Spaghetti Western. It’s safe to say he struck pay-dirt while doing so.

Leone’s so-called “Dollars Trilogy,” which ended with 1966’s The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly did not make it to American shores until a couple years later, having already catapulted Clint Eastwood to international, first-name-only super-stardom. When the genre did finally arrive in 1967, it ushered in a new age of the Western—harsher even than 1956’s The Searchers and more disillusioned than 1962’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. 1969 would see two major films that set a new tone for the changing genre forever: The Wild Bunch and Once Upon a Time in the West, which came over to America after having been released internationally the previous year.

A lot of people think of The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly or even For a Few Dollars More as Leone’s best Westerns. I still argue that Once Upon a Time in the West holds that spot for a number of reasons, not the least of which being that it was perhaps his most ambitious film to that point, and crystallizes ideas that Leone was just forming in those former two.

For a Few Million More

It’s difficult to overstate just how successful Leone’s earlier films had been financially. For relatively paltry budgets at the time, United Artists was seeing incredibly high returns. A Fistful of Dollars was made for about $200,000 (a figure slyly inserted into The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly) and pulled in $14.5 million from the United States alone. Leone used about $5 million to make Once Upon a Time in the West, an astronomical sum compared to his earlier budgets. Yet, the movie almost didn’t happen for the simple reason that Leone did not want to make another Western.

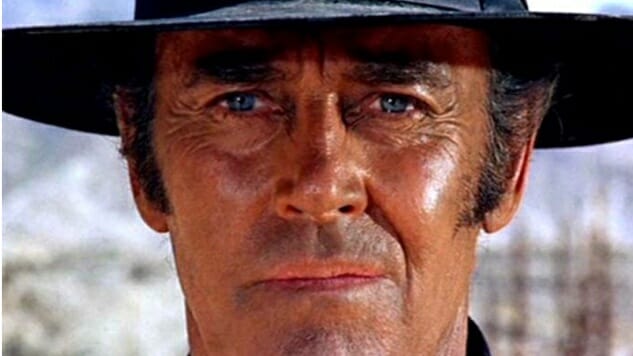

Fortunately for audiences, United Artists only wanted to give Leone money to make more of them, and they sweetened the deal by promising him Henry Fonda—an actor for whom Leone had expressed deep respect. Clint Eastwood turned down the role of Harmonica, and it went to Charles Bronson, starting him on the path that would eventually lead him to Death Wish.

It’s worth it to mention, too, that composer Ennio Morricone, who is doing some of the best work of his long and distinguished career in this movie, never had much affection for his Spaghetti Western compositions at all. It boggles the mind to conceive how he could unleash iconic score after iconic score while eyeing the clock like that.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-