Project Nim review

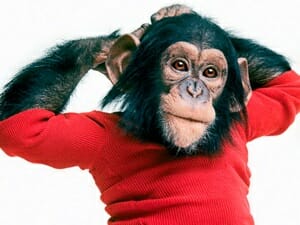

Project Nim is the fascinating and exquisitely executed new documentary by the makers of Man on Wire, Paste’s documentary of the decade.

In Man on Wire, director James Marsh recounted French tightrope walker Philippe Petit’s exploits, most notably his unauthorized 1974 walk between the Twin Towers that held most of the city of New York breathless for an entire morning. In Project Nim, a team of researchers (only one year earlier, in 1973) sets out to accomplish an even more audacious and thrilling goal—to teach a chimpanzee human sign language and initiate meaningful dialogue.

Technically the film is flawless. The story is told largely from the point of view of the participants (all of whom agreed to be interviewed for the film), but because of the high profile nature of the experiment, there’s a lot of archival video footage and photography to keep things from turning too talking-head-heavy. Marsh also makes judicious use of recreations, but anyone who’s seen Man on Wire knows that he handles that technique well; the thrilling and heartbreaking opening scene alone will dispel any worries by anyone else. There’s a running motif of large words sliding across the screen, which bookends and illuminates conversations well, adds a great deal of visual interest, and ties in nicely to the idea of Nim learning sign language (since the titles themselves are a sort of visualization of language). Dickon Hinchliffe (Winter’s Bone) adds a fantastic score that achieves a difficult task—capturing the excitement of the project and its promise while also suggesting a deep foreboding.

But the most compelling aspect of the story told by Project Nim isn’t just the implications for the conversation about animal rights. Nim’s latter-day suffering is heartbreaking, but it’s predominantly due to his being denied the opportunity to grow up as a normal chimpanzee. Nearly no animals face a similar predicament, and nearly everyone would agree that such an animal deserves special treatment rather than being warehoused with others who were able to develop more sophisticated survival and coping skills (or at least more suited to the environment in which they live).

No, the really compelling angle for the film is the very idea of inter-species communication. Decades of science fiction films, notably Spielberg’s milestone Close Encounters of the Third Kind, have long tapped into the primordial power of the question “Are we alone in the universe?” But the experimenters in Project Nim were looking to create a different type of contact with the animals that have been right in front of us all along. It helps, too, that chimpanzees look and act, at times, in ways that are uncannily human.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-