The 10 Best Sci-Fi Movies of 2024

The best sci-fi movies of 2024 tackle the kind of elemental questions around which the genre has always revolved: What is the value of a human life? How much are you willing to sacrifice, to get something you want? How will technology continue to transform our ability to travel, to communicate with each other, to experience life’s pleasures and sorrows? Will we ever learn from our mistakes and treat each other with dignity, or will each new discovery simply force us through another round of learning the same lessons?

This year, the sci-fi film genre saw human DNA merging with animals in the likes of The Animal Kingdom, or human consciousnesses being stripped away and replaced with alien hitchhikers in Meanwhile on Earth. It saw the impacts of desperation in clinging to one’s golden years in Coralie Fargeat’s The Substance, or the alternatingly melancholy and uplifting journeys of The Beast and the still underseen Robot Dreams. We got all that, and the blockbuster bombast of George Miller returning to his Mad Max setting in Furiosa, as well.

Here are the 10 best sci-fi movies of 2024:

10. The Animal Kingdom

Director: Thomas Cailley

The Animal Kingdom writer/director Thomas Cailley blends traditional French social realism with one major element of science fiction (humans turning into animals) to create a dystopian drama that focuses on a small, character-driven story in order to evoke a vaguely environmentally conscious message.

Émile (Paul Kircher) is your average teen boy, worried about normal teen boy things, like making friends at his new school. Émile’s father François (Romain Duris) moved the two of them, along with their dog Albert, south in order to accommodate for the medical care of Émile’s mother, who is transforming into a beast. François is fiercely devoted to his wife’s recovery, while Émile would rather pretend that his dad is a widower. When the van transporting the half-animals, half-humans crashes and his wife escapes into the woods, François becomes determined to find her, with the help of a nice cop named Julia (Adèle Exarchopoulos). Things get even hairier for Émile when he both meets a cute girl he likes, Nina (Billie Blain), and realizes that his mother’s unfortunate genetic condition may be hereditary, as he begins to slowly transform into a wolf.

The Animal Kingdom is most interesting if taken as a movie about Mother Nature curing herself of the disease of humanity by forcefully grabbing us humans back into her tendrils. She has the power to give us human consciousness and the power to take it away. Where does the line between human and animal lie? When does Émile’s mother stop being his mother—stop being human? When does it become acceptable to gun the creatures down, now that they have been othered? —Katarina Docalovich

9. I.S.S.

Director: Gabriela Cowperthwaite

Dr. Kira Foster (Ariana DeBose) is the newest member of the I.S.S. crew, a biologist who joins NASA to develop cutting-edge organ replacement research that can save lives. She joins a team that’s a 50/50 split between American astronauts and Russian cosmonauts, a seemingly friendly bunch who carry out a warm welcome celebration for the fresh recruit on her first day. However, during the merrymaking, a colleague offers a word of advice: To work in harmony, it’s essential to leave politics at the door.

Unfortunately, this tip becomes difficult to follow after the group witnesses something unbelievable. While looking down at North America, they witness a flash on the surface so big it can be viewed from orbit. And then another, and many more. High-ranking NASA astronaut Gordon Barrett (Chris Messina) and his Russian counterpart Nicholai (Costa Ronin) receive private messages from their respective governments that America and Russia have engaged in a nuclear war. They both receive orders to take the station “by any means necessary.” Delivering close-quarters anxiety, I.S.S. is unrelenting. Shortly after its early turning point, tensions exponentially escalate as these people size up if they think their former friends can do the unthinkable. Nick Remy Matthews’ intimate camerawork captures this constant proximity to potential enemies, and early scenes are rife with the captivating sense that things will go sideways at any moment. —Elijah Gonzalez

8. Mars Express

Director: Jérémie Périn

Mars Express is an unabashed genre flic from director Jérémie Périn and French studio Everybody on Deck. The noir thriller takes us on a contemplative tour of a thoughtfully considered future, where traveling between Lunar and Martian colonies is as easy as flight today.

We follow Aline Ruby (Morla Gorrondona), some sort of cop investigating a mysterious disappearance and murder linked to unusual behavior among the humanoid robots of a patron corporation—and it’s filled with all the tropes of the setting and story you might expect. It’s a setting where humanoid robots (think Asimov) and transhumanist tech (think Oshii) are commonplace, prodding at the boundary between life and creation.

Mars Express’ art direction isn’t particularly moving, lacking striking visuals that could easily live alongside its inspirations. Its script (from Périn and Laurent Sarfati) is similarly just a bit too quiet for its own good—there’s no moment where the hooks sink in to you. Mars Express rides instead on moments like a cat’s skin zipping off to reveal a mechanical frame beneath, or in considering all the implications of artificial mind and body duplication (ranging from espionage to sex work). If you linger in its world long enough for a second viewing, there’s much to appreciate. —Autumn Wright

7. It’s What’s Inside

Director: Greg Jardin

Masks are important in horror movies, but not just the ones you can pluck off a shelf and wear. Jason, Michael, and Ghostface all have their masks, of course, but a good horror film can also focus in on the masks we as regular humans wear at work, at home, or among friends. Who we really are versus who we hope we are is a source of phenomenal dramatic tension in any genre. Throw in some horror concepts and some scary atmosphere and you’ve got what’s (hopefully) a compelling concoction about the fear of facing your true self, and the fear of learning those closest to you aren’t who you thought they were.

It’s What’s Inside, the new horror/sci-fi/comedy from writer/director Greg Jardin, is certainly compelling, but it’s what the film does beyond the basic tension of challenging its characters on their own identities that makes its special. Fiendishly clever, beautifully designed, and driven by a great ensemble, it’s a genre-hopping romp that plays like the perfect movie for a Friday night in October, even as it also functions as a nerve-shredding exploration of the masks we wear. It’s a film about masks, yes, but also about mining the insecurities, fears, and longing of others to get to the truth of who you really are, then realizing you might not like the results. It’s a smart, sexy, riotous assault on the senses, and it deserves a spot on your Halloween watchlist. —Matthew Jackson

6. Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga

Director: George Miller

Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga is the Iliad to Fury Road’s stripped-down Odyssey. The latter’s elegant straight-line structure is replaced with lush chapters, documenting the interconnected systems of post-apocalyptic nation-gangs through the years. Through it all, a Dickensian hero clings to this world’s seedy undercarriage. Reducing Furiosa down to a single word does it as little justice as it does the sagas it scraps, welds and reuses like its countless Frankenstein vehicles. But understanding George Miller’s Fury Road prequel as the story of war—of sprawling futility, driven by the same cyclical cruelty that turned its deserts into Wastelands—makes it far more than a satisfying origin story. (Though, it’s that too). Furiosa speaks the language of epics fluently, raging against timeless human failure while carrying a seed of hope.

While any structure would be more complex than a pair of perfect car chases, Furiosa’s script necessarily evolves to match its more expansive narrative. That said, Miller and co-writer Nico Lathouris still aren’t here to coddle us with over-explanation or endless Easter eggs. I don’t want to know how the world fell, or how Furiosa got her name. I want to meet a piss-wielding boy named Piss Boy.

Pushing back on the various men who hunt them, Alyla Browne and Taylor-Joy’s performances work in stunning tandem, steadily heating the steely young girl’s resolve until it turns molten. Browne coils and pounces, while Taylor-Joy’s physicality is more refined and sure-footed. You can even feel the influence of Charlee Fraser, who leaves a strong impression in her brief scenes as Furiosa’s mother. All three beam stares into the screen that would set celluloid on fire. Every hard edge Furiosa has in Fury Road is sharpened here, and every moment of tenderness given deeper roots. Furiosa might actually speak less in this movie than in Fury Road, which makes what her two performers pull off even more impressive. When you match the most powerful eyes in the business with Miller’s evocative framing (Furiosa is shot a bit like Galadriel’s brush with evil in Lord of the Rings—somewhere between avenging angel and Frank Miller cover), you get all the character you need. —Jacob Oller

5. Dune: Part Two

Director: Denis Villeneuve

Set aside the complicated calculus of food, shelter and family needs. It’s time to shell out the big bucks and head to the local IMAX. To borrow from Nicole Kidman’s AMC commercial more explicitly, though you might not be “somehow reborn,” there will be “dazzling images,” sound you can feel and you will be taken somewhere you’ve “never been before” (at least, not since Dune). As befits a Part Two, Villeneuve’s film picks up in medias res, with Paul Atreides (Timothée Chalamet), his mother Lady Jessica (Rebecca Ferguson) and the Fremen encountering and dealing with a murderous Harkonnen hunting party while trying to reach the Fremen stronghold. From this encounter, Villaneuve nimbly guides the narrative from one key moment to the next, a veritable dragonfly ornithopter of plot advancement (with a few slower moments to allow the burgeoning relationship with Paul and Zendaya’s Chani to breathe). If the outcome of each narrative stop feels very much fated, that in turn feels appropriate given the messianic prophecy undergirding the entire tale. Dune: Part Two’s production design is as much center stage as its star-studded cast. Villaneuve pummels the viewer with the sheer scale and brutal, industrial efficiency of the Harkonnen operation—well, it would be efficient if not for those pesky Fremen—yet all of it is engulfed in turn by Arrakis itself. Meanwhile, the sound design and throbbing aural cues evoke the weight and oppressiveness of a centuries-spanning empire, the suffocating cunning of “90 generations” of Bene Gesserit schemes and the inescapable gravity Arrakis and its spice-producing leviathans exert on both. For those torn on whether it’s worth venturing forth to the multiplex, consider Dune: Part Two a compelling two-hour-and-forty-six-minute argument in the “for” column. And that “indescribable feeling” you get when “the lights begin to dim?” That’s cinematic escape velocity, instantly achieved. Next stop, Arrakis. –Michael Burgin

4. Robot Dreams

Director: Pablo Berger

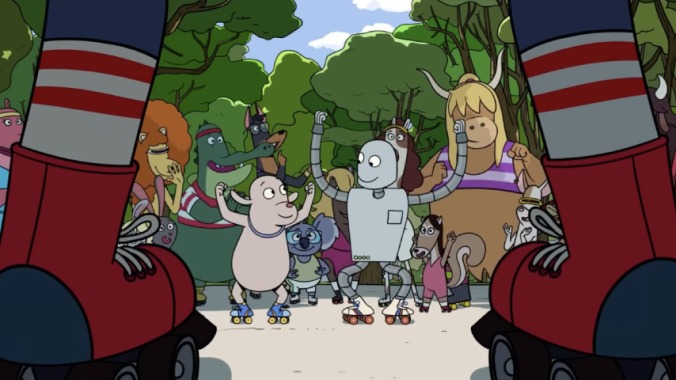

Robot Dreams was at least to some extent lost in the hubbub of this past year’s Academy Awards for one primary reason: Pretty much no one in the U.S. had actually had a chance to see the film at the time. Nevermind the fact that it competed for the Oscar for Best Animated Feature back in March–all of the conversation at the time was revolving around choices either far more populist (Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse) or from creators so revered that they’ve achieved mythological status, as in Miyazaki’s The Boy and the Heron. It’s unsurprising that Spanish director Pablo Berger’s sweet but emotionally resonant Robot Dreams was more or less swept under the rug, but its eventual arrival in U.S. theaters and streaming services in 2024 has allowed American viewers to finally realize what they had been missing: One of the most charming and tear-inducing, wordless stories of friendship we’ve been gifted in recent memory.

Robot Dreams is a classic story of loneliness and friendship, as created in the relationship between Dog, a mute resident of a beautiful version of NYC occupied by anthropomorphic animals, and Robot, the sentient automaton who becomes his closest companion. On its own, that premise might provide enough material for a short film, but Robot Dreams ventures into unexpectedly poignant territory when a series of accidents forces the two apart. Again, one expects convention to step in, for Robot Dreams to coalesce into a story about finding your friend against all odds and refusing to give up. But instead, it eyes these events with both a pragmatism and emotional maturity that is refreshingly and distinctly realistic: Dog and Robot both find a next phase in their lives, without needing to let go of how much their time together meant to both. Few would-be comedies or dramedies of this sort are so adept at holding both POVs at once: The simultaneous sense of profound loss at having drifted away from a former close relationship, but also the acceptance, cherishment of the memory, and hope for a future of new, novel experiences. Robot Dreams recognizes that emotions don’t happen sequentially, but all at once, and captures it in beautifully fluid animation as it brings to life a lovingly rendered portrait of New York at the same time. —Jim Vorel

3. The Beast

Director: Bertrand Bonello

Most filmmakers will never need to locate the rhythm in cross-cutting between multiple time periods separated by a half-century or more and augmented by sometimes-obtuse sci-fi concepts; it simply isn’t a common occurrence outside of movies like Cloud Atlas, of which there are vanishingly few in the grand scheme of things. Say this for Bertrand Bonello’s The Beast: It is, in fact, a movie like Cloud Atlas. Not as good, not as arresting, not as visually stunning, but nonetheless a sort-of-humanist, sort-of-sci-fi story that places its leading actors in multiple storylines taking place decades or more apart. That alone is exciting, even as the movie demonstrates just how difficult a feat this is to pull off.

If you’re going to watch an actress for a century-plus, however, Léa Seydoux is a solid choice. She plays Gabrielle, a woman in 2044 who is prodded into having her DNA “purified,” a common procedure in a world where artificial intelligence has rendered human employment largely obsolete. People can re-enter the workforce by having their memories and emotions more or less purged, rendering them closer to employable automatons. This evocatively depicted process zaps Gabrielle into a kind of dream-memory state where she recalls past lives in 1910 and 2014. In both of them, as well as in 2044, she crosses paths with versions of Louis (George MacKay). Are they star-crossed lovers, or something more malleable? Does our body contain memories past our physical lives? And how, by the way, does Bonello adapt (however loosely) a Henry James novella (The Beast in the Jungle) that was published seven years before this movie’s earliest timeline? If it all sounds heady, it’s actually more straightforward to describe than to experience. —Jesse Hassenger

2. The Substance

Director: Coralie Fargeat

In terms of sheer dominance over The Discourse, there can be no doubt that 2024 belonged body, mind and soul to Coralie Fargeat’s The Substance. A quantum leap forward in terms of ambition and sophistication after her slick but streamlined 2017 debut thriller Revenge, The Substance is an ode to self-destruction and bruised egos, greed and blindness to cycles of perpetuated avarice.

Much of the film’s success comes down to the incredible willingness that Fargeat taps into in its performers to make themselves as reprehensible–and yes, “ugly”–as possible, becoming portraits of desperate individuals who have long since abandoned common decency or a shred of empathy. That of course includes Demi Moore’s Elisabeth, who pathetically clings to the faintest shreds of vicarious achievement despite the fact that she can’t really enjoy them, addicted to the rush of seeing her avatar succeed even as she resents herself and physically drains herself dry. It includes Dennis Quaid’s not-so-subtly named Harvey, a slavering psychopath who treats his talent with no more respect or tact than he puts into masticating an entire plate of shrimp in a sequence that rivals any of the other stomach-churning sights of The Substance. And the willingness to tap into the depraved side of human nature even applies to Margaret Qualley’s pristine Sue as well, a woman so eager to debase and objectify herself just to live up to the archaic standards of success once set by Elisabeth, never once considering that her unique circumstances could afford her a second chance to live life different than Elisabeth previously did “in her prime.” The tragedy of The Substance is that Sue can’t even conceive of a more fulfilling alternative than willingly throwing herself into the exact same meat grinder that chewed up Elisabeth and spit her out, except Sue is apparently determined to speedrun the entire process.

On a thematic and visual level, The Substance has perhaps been given more credit at times for its outrageousness or uniqueness than it necessarily demands, which mostly serves to illustrate how this kind of boundary stepping body horror has become a rarity to see on a big screen in recent years. Reactions to the film almost serve as a litmus test for whether any prospective horror geek has ever gotten around to seeing Brian Yuzna’s Society from 1989–if you have, then you probably find Fargeat’s film a bit less shocking. But the sheer, unapologetic gusto with which The Substance tackles its squelchy, bone-cracking delights makes its combo of visceral transformation and misanthropic satire into a vital piece of modern horror filmmaking, anchored by some of the best performances the genre has seen in recent memory. —Jim Vorel

1. Meanwhile on Earth

Director: Jérémy Clapin

Great science fiction filmmaking so often boils down to elemental, poignant themes on the nature of ethical choices and how these moments can transform our lives: Crossroads moments, where the paths of possibility diverge in opposite directions. Choose one path, and perhaps you retain your humanity at the cost of your own destruction, be that physical, emotional, spiritual or symbolic eradication. Choose the other, and perhaps you sacrifice your soul for some other aim, altruistic or personal. Is the choice worth the cost? In the end, we each must decide for ourselves, as protagonist Elsa (Megan Northam) is made to do in the emotionally wracking and visually engrossing new French sci-fi drama Meanwhile on Earth.

Elsa’s family, and by extension her own personal development, are both encased in a casket of grief, slowly suffocating as they linger in stasis. Three years earlier, her brother Franck disappeared during an exploratory space mission, his ultimate fate unknown but safely assumed by all. His small town in the French countryside erected a statue to their fallen local hero in the center of a traffic roundabout, which Elsa feels compelled to occasionally deface not in opposition to her brother but as a way to retain some kind of symbolic ownership of his memory. Her family unit is frozen in place: Father entombed in his basement office, listening to crystalline piano concertos, mother and daughter working at the same senior memory care facility, where they provide succor to patients who have outlived all other forms of familial aid. For Elsa, the job was supposed to be temporary, something to help keep her busy and get her back on her feet following the disappearance of Franck, before she returned to her true passion for illustration and comic book art school. But without Franck’s motivating presence, his ceaseless support and energizing drive, Elsa is now stuck in place, lacking the inertia to truly restart her life. And that’s about when she first hears a voice from above.

Although as anyone who sees Meanwhile on Earth will probably conclude, “above” is entirely relative in this equation. Where Franck and his spaceship have truly gone is an open question, allowing for the possibility that they have transcended time and space itself. And when Elsa begins to hear these voices, the implication is that she may be hearing them across the gulf of dimensional borders (if she’s not crazy), able to do so thanks to the opening of a fleeting “path” that only she can access, thanks to her emotional or psychic connection with Franck. But wherever he is, he’s by no means alone.

Meanwhile on Earth is the mournful sophomore feature from director Jérémy Clapin, and like his beautiful, Oscar-nominated animated debut I Lost My Body from 2019, it delves into metaphysical themes of identity, self-worth and compartmentalization: How do we value others, and ourselves? What are the individual parts of us worth, and which parts make a whole? Can a person be complete on their own, without the ones they love? The film’s basic premise forces Elsa into confrontation with one of the most elemental moral dilemmas of all: What is the value of a human life? —Jim Vorel