Sugarcane Compassionately Confronts the Legacy of Residential Schools

The last residential school, the abusive Christian-run institutions created to assimilate Indigenous children across North America into the white world, closed in 1997. I was five years old, starting first grade in Broken Arrow, Oklahoma, a city named by Creek people, who had arrived after being forced to walk the Trail of Tears from Alabama. My elementary school’s mascot was the Pioneers, which is a polite way of saying “colonists,” which is a polite way of saying “thieves.” Of course the residential schools lasted until the late ’90s, and of course the harm they caused still resonates throughout Indigenous communities. The last few years especially have seen both fiction and nonfiction reckonings—ranging from the poetic reeducation of Lakota Nation vs. United States to the genre work of the late filmmaker Jeff Barnaby—with the brutal, federally-mandated violence of residential schools. Few cinematic takes have been as beautiful and compassionate as Sugarcane. From subject/director Julian Brave NoiseCat and director/journalist Emily Kassie, the documentary gives faces, names and histories to those affected by the residential schools—and looks, bracingly, towards a future where healing is possible.

The impact of these schools is so pervasive and lasting, that even this couched optimism can feel impossible. This is especially true when zeroing in on the members of the Williams Lake First Nation. You’d be hard-pressed to find someone in the WLFN, whose main reserve is British Columbia’s Sugarcane, who wasn’t affected by the violence and sexual assault at the notorious St. Joseph’s Mission residential school. This school in particular featured such rampant, prolific abuse that an anecdote of its evils led to the Canadian holiday National Day for Truth and Reconciliation. Sugarcane allows the full extent of this tragedy to play out in details, like Chief Willie Sellars buying an awareness-raising box of orange donuts, and in asides, like Prime Minister Justin Trudeau facing criticism after he speaks at a local event.

While the investigation into St. Joseph’s—both in searching for missing children (in mass graves through ground radar or elsewhere) and in drawing lines of accountability through the various principals in charge of the school—allows longtime expert and advocate Charlene Belleau and her team to share context about the massive scope of this sin, Sugarcane hits hardest when staying personal. We’re well aware of the Catholic Church’s reputation. So aware, in fact, that we can be numb to each new horror story about it. NoiseCat and Kassie put us through targeted treatments to return our sensitivity, starting at home.

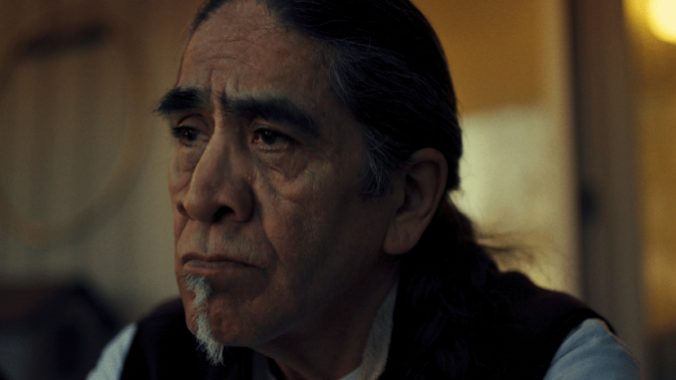

NoiseCat and his father Ed are our two closest subjects during Sugarcane. Their confrontational yet loving trip through the latter’s past embraces the double-edged joy and pain of intimacy. They goof around, singing Neil Young and quoting Eminem songs, and hurt each other deeply. As Ed, born at St. Joseph’s under circumstances so painful that his own mother won’t speak about it, recalls his endurance of a complicated childhood, his son bristles at the hypocrisy. A father who left, concerned about an absent parent? But things are finally getting candid, which means the wounds have a chance to close. Anger melts into empathy, as what first looks to be hypocrisy reveals itself as a predictable point in a cycle.

The other two men we spend the most time with are Chief Sellars and former Chief Rick Gilbert, who act as perfect symbols of their eras as well as endearing individuals. Sellars maintains and preserves this history while dealing, on a community level, with its continued fallout. He politely responds to viciously racist hate mail and, when it rears its head, talks seriously with his young children about suicide. Directly after this conversation, NoiseCat and Kassie cut to footage of a trio of drunk seniors waiting for the bus. We get the message: Statistically, these are the two common endpoints for the Indigenous road. It’s not shot through with pity, nor with outsized dignity. Just the sad facts, given faces.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-