Ping Pong Summer (2014 Sundance review)

The problem with basing an entire movie on nostalgia is that while it may hit your target audience right in its sweet spot, for everyone else it may seem like little more than an extended version of “Guess you had to be there.” Where one person might get a quiet thrill seeing an 8-track player on screen, another may be more likely to giggle with recognition over a boom box or a portable CD player—the childhood memory can be palpable, but it’s also frustratingly specific. Writer-director Michael Tully’s Ping Pong Summer gets all its comic mileage out of its affection for mid-’80s detritus—not just the cultural artifacts of the era but also the period’s coming-of-age sports movies—and while that’s a thin thread on which to hang a whole film, there’s enough goodwill and charm here for it to work.

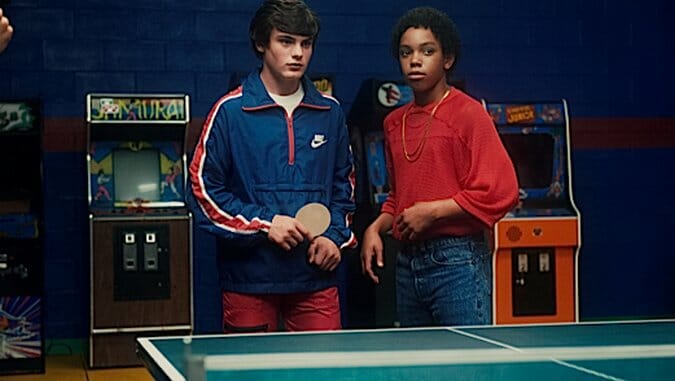

Set in the summer of 1985 in Maryland, Ping Pong Summer is essentially a Karate Kid rewrite done in the world of table tennis. Rad (Marcello Conte) is a breakdance-loving dorky teen who goes with his family to a touristy beach town, in no time acquiring a close buddy (Myles Massey) who shares his fascination with rap music, a pretty love interest (Emmi Shockley), and a cocky nemesis named Lyle (Joseph McCaughtry) who like Rad digs ping-pong. In the Mr. Miyagi role, there’s Susan Sarandon’s Randi Jammer, a local enigma who barely talks to anyone and prefers to hide behind her big black shades and air of mystery. With Randi’s help, Rad is going to train to beat Lyle in a ping-pong showdown.

Tully’s story could perhaps work as a five-minute sketch thanks to its emphasis on choice pop-culture references: ICEE drinks, the permed hair, the annoyance of having to rewind a cassette tape to get to the song you want. But while Ping Pong Summer doesn’t try to dig into its nostalgia—this isn’t a film that uses its period setting as a springboard for some broader cultural commentary—it exhibits a modest appeal that’s so casual and innocent that it lowers your guard. And what soon becomes clear is that Tully doesn’t just genuinely love the era he’s documenting; he also loves the people who populate it.

-

-

-

-

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 3:10pm

-

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:57pm

- Urls By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:57pm

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:55pm

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-