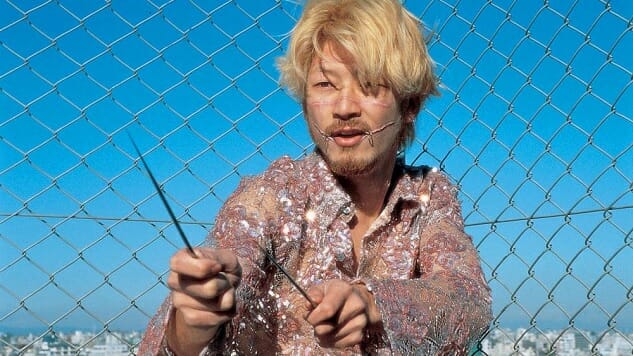

Ichi the Killer Doesn’t Need Your 4K

There are movies that benefit from 4K restorations, movies that demand 4K restorations, and movies that should never be given 4K restorations because even a single K would be one K too many. Case in point, Takashi Miike’s Ichi the Killer, a grimy movie about grimy things once available in strictly grimy presentations, now gussied up by Well Go USA in a 4K remaster: They get an “A” for effort, but an ASCII shrug for intent. Ichi the Killer isn’t for the faint of heart, epileptics, priests, expectant mothers, or really anybody with even a very mild aversion to apathetically graphic depictions of violence and torture. Murky cuts of the film are the most palatable. Higgledy piggledy piles of human organs should never be seen with this much clarity.

All the same, Ichi the Killer’s restoration throws Miike’s career trajectory into sharp relief, especially as his new film, Blade of the Immortal, arrives in theaters and on VOD for consumption by a niche moviegoing audience whose memories of Miike’s shock cinema roots have softened as his choices in late-stage projects have become more refined (or, if nothing else, less unabashedly deranged). Not that Miike will ever be thought of as a sophisticated filmmaker, even if his filmmaking is itself sophisticated: He’s too self-possessed, too much an inveterate transgressive artist for high-minded honorifics and accolades. He makes one kind of film—Miike films—and the world is richer for that no matter how nauseating and outright strange those films so often happen to be.

With Well Go’s treatment on Ichi the Killer running at New York City’s Metrograph at the same time that Blade of the Immortal premieres in theaters, that Miike dichotomy is made newly visible. Both films are about revenge. Both films hinge on scenes of carnage and blood-splattered action. Both of them prominently feature characters with visible scars, worn like fashion statements more so than past wounds. But restoring Ichi the Killer makes as much sense as dressing up Leatherface in a Brioni one-button tuxedo: It looks fabulous, but gruesome exploitation that looks fabulous is still gruesome exploitation. By contrast, Blade of the Immortal looks fabulous right out the gate. There’s no dressing up needed. The film is a natural stunner.

One may cynically call Blade of the Immortal a glossy, commercial version of a Miike film, and they’d be half wrong. It’s impeccably made, but hardly qualifies as commercial. Miike sacrifices little of his personality in adapting Hiroaki Samura’s manga series for the big screen, coupling its various eccentricities with his own directorial flourishes: Unsurprisingly there’s gore aplenty, and the cast of characters includes a samurai with severed heads mounted on his armor, a beautiful courtesan-cum-assassin with a conscience, an unkillable swordsmen, and a nun who apparently wanders the countryside searching for skilled, damned warriors to serve as hosts for parasites that give their hosts immortality. (It’s a more complicated than that, but not by much.) The hero has a literal armory hidden up his sleeves. One shake of his arms and piles of weapons tumble right out. It’s Looney Tunes-level stuff in a genre that’s anything but cartoonish.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-