Cowabunga! Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles Is 30!

Jim Henson helped turn the send-up of grim-dark comics into an invincible franchise.

“Oh god,” my father groaned at the first ad spot for the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles movie in 1990. “I am not taking you to that.”

He totally did, though. And later he conceded that it was actually a “pretty good” movie. It is some kind of minor miracle that it is, a testament to how fervently everybody involved must have believed that they could make something entitled “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles” memorable and unique when just the title alone plants it exactly at the year 1990, right at the tail end of the action movie ninja craze of the ’80s and right at the beginning of the color-change neon ’90s.

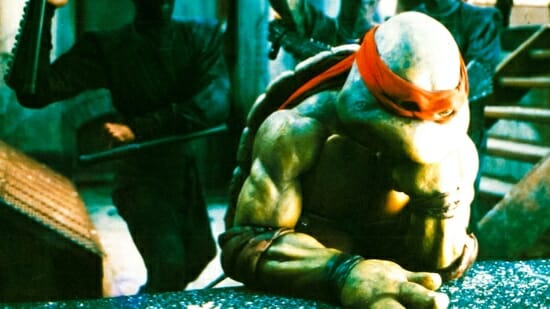

How did some stunt men in 50-pound rubber turtle costumes (one of them voiced by Corey Feldman) work so well? Why on Earth am I—one of the kids in the target audience who saw this when it debuted in theaters—on the way to 40 while this franchise still regularly reboots itself in cartoon series after cartoon series?

The movie starts with TV news reporter April O’Neal (Judith Hoag) expositing on a wave of petty theft sweeping New York, intercut with scenes that show us the perpetrators are being organized by actual freaking ninjas. When April is accosted by the ninja clan for revealing their existence, she’s rescued by the turtles, sewer-dwelling ninjas who are the result of an accidental exposure to a bright green mutagen.

Under the ninja tutelage of the mutant rat Splinter (voiced by Kevin Clash), the turtles fight the Foot Clan, a group of ninjas using disaffected teens as a recruitment pool, plying them with videogames and cigarettes (regular or menthol) and training them up as ninja enforcers. We learn that the ringleader is the menacing Shredder (James Saito, dubbed over with a deepened, distorted, evil voice by David McCharen), and it becomes clear that he’s actually a sinister figure from Splinter’s past. Our view inside Shredder’s pied piper operation comes courtesy of Danny (Michael Turney), the son of April’s boss, who runs away from home and forges a connection to the kidnapped Splinter. There is also, apropos of precisely nothing, a vigilante hockey player named Casey Jones (Elias Koteas) who joins the turtles for basically no reason.

As convoluted and weird as it all sounds, the movie doles out exposition carefully, interspersed with ninja fights and quiet little moments between characters where they simply play off one another. There are major problems with the script: This is a movie where a character we last met beating up one of the turtles inexplicably decides to team up with them against a horde of ninjas and the good guys don’t once come face-to-face with the bad guy until the last scene. It nonetheless is a delightful watch, equally adept at earnest acting and martial arts slapstick, with quotable lines delivered with such glee that they chisel into the brain stem of the viewer.

One major reason it works so well is that Jim Henson’s turtle-suit designs make the main characters incredibly expressive and lifelike, even as the actors had to navigate sets and conduct ninja stunt fights while gazing out of the suits’ mouth-holes. (It was Henson’s last project: He died shortly after the film debuted.)

The movie struggled to find a distributor before finally landing at New Line Cinema and coming in ninth at the box office that year, ahead of Kindergarten Cop and behind stuff like Pretty Woman, Back to the Future Part III and Home Alone.

Critics of the time did not agree with me: The movie maintains somewhere in the area of 40% on Rotten Tomatoes (still the highest-reviewed of its decades-long franchise), and Ebert gave it the faint praise of calling it “nowhere near as bad as it might have been.” It nonetheless broke box office records, and proved so popular that the franchise has been present somewhere ever since. There have been four or five television shows since the 1987 original alone.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-