Best of Criterion’s New Releases: January 2024

Each month, Paste brings you a look at the best new selections from the Criterion Collection. Much beloved by casual fans and cinephiles alike, Criterion has presented special editions of important classic and contemporary films for over three decades. You can explore the complete collection here.

In the meantime, because chances are you may be looking for something, anything, to discover, find all of our Criterion picks here, and if you’d rather dig into things on the streaming side (because who’s got the money to invest in all these beautiful physical editions?) we’ve got our list of the best films on the Criterion Channel. But you’re here for what’s new, and we’ve got you covered.

Here are all the new releases from Criterion, January 2024:

The Apu Trilogy: Pather Panchali, Aparajito, Apur Sansar

Year: 1955, 1956, 1959

Director: Satyajit Ray

Stars: Subir Banerjee, Kanu Banerjee, Karuna Banerjee; Pinaki Sengupta, Kanu Banerjee, Karuna Banerjee, Smaran Ghosal, Ramani Ranjan Sengupta, Charaprakash Ghosh, Subodh Ganguly; Soumitra Chatterjee, Sharmila Tagore, Alok Chakravarty, Swapan Mukherjee

Runtime: 125 minutes; 110 minutes; 106 minutes

Pather Panchali feels like a product from an amateur. There is something very raw about it, with many of the actors appearing on screen for the first time and a lack of experience from the crew. For example, his cinematographer Subrata Mitra was a still photographer that Ray convinced to join the production. Great filmmaking sometimes occurs from great risk, and in this case a masterpiece was made. Apur Sansar actor Soumitra Chatterjee said during a Criterion Channel interview, “Experts will perhaps say that all of Satyajit Ray’s other films are technically superior…but Pather Panchali’s vitality and intensity are like an eagle swooping down and carrying our hearts up to the sky.” Each of the films explore different aspects of Apu’s life. Pather Panchali explores the village lifestyle and Apu’s relationship with his sister, Aparajito finds Apu and his family moving to Varanasi and Apur Sansar shows an adult Apu making his own family. Each of the films focus not only on the physical and mental growth of Apu, but also the brief time he shares with his relatives over his life. What makes The Apu Trilogy so memorable is how the lives of Apu and his family become part of us as the movies roll on. Roger Ebert once spoke about how movies are the great “empathy machine” that allow audiences to inhabit the lives of others. Even if you can’t initially imagine relating to this family from a small village, the great power of The Apu Trilogy magically brings us into a world and features life changes that all can relate to. That is the true secret of Ray’s cinema.—Max Covill

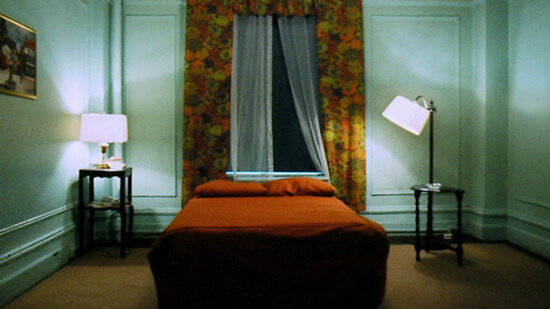

Blood Simple

Year: 1955

Director: Joel Coen

Stars: John Getz, Frances McDormand, Dan Hedaya, Samm-Art Williams, M. Emmet Walsh

Runtime: 96 minutes

Blood Simple introduced the world to the cinema of Joel and Ethan Coen, and the world has been a better place ever since. The brothers, of course, went on to bigger budgets, Oscar victories and a variety of genres, but their writing and directing were already in top form when they made this stylish noir thriller. John Getz, Frances McDormand and Dan Hedaya are all excellent in the story of an increasingly bloody romantic entanglement, and M. Emmet Walsh steals the show as a sleazy private detective. But the real stars are the Coens, as they build on a nightmare scenario with taut suspense and a cheeky sense of humor. —Jeremy Mathews

Lone Star

Year: 1996

Director: John Sayles

Stars: Chris Cooper, Kris Kristofferson, Matthew McConaughey, Elizabeth Peña

Runtime: 135 minutes

John Sayles weaves a slow-burning, incredibly intricate reckoning in the Texas border locale of Rio County. Sheriff Sam Deeds (Chris Cooper), struggling to escape the shadow of his late father, Buddy (played in flashbacks by Matthew McConaughey), stumbles upon human remains and with it a 40-year-old murder mystery that spotlights racial tensions and suspicions of institutional corruption. As the sins of much hated Sheriff Charlie Wade (a menacing Kris Kristofferson) are laid bare, Sam wonders if his dear old dad was involved in the offing. In the meantime, he reconnects with the high school sweetheart (Elizabeth Peña)—fittingly, she’s a history teacher—he had been separated from because of their ethnic differences. In a town where blacks, whites, Mexican Americans and Seminole Indians have different takes on what precipitated the raging bigot Wade’s demise, Lone Star considers the extent to which cultures, politics and generations coexist, how they “come together in both negative and positive ways,” in Peña’s words, an upside-down societal fabric in which the majority is still oppressed by the minority. It’s intelligent, gracefully nuanced and resonant. —A.S.

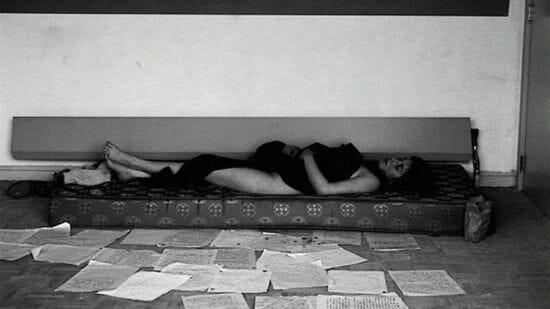

Saute ma ville

Year: 1968

Director: Chantal Akerman

Stars: Chantal Akerman

Runtime: 13 minutes

Chantal Akerman’s first film, Saute ma ville, is best understood in relation to one of the director’s feature films. A 13-minute black-and-white film she made while only in her teens, it looks rather like any other amateur experimental film from the ’60s and ’70s except when put alongside its big sister Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles. An explosion is in fact exactly what Akerman infused into Saute ma ville, which came seven years before Jeanne Dielman and attacks the same problem but in a very different way. The literal English translation of its title is “Blow Up My Town,” so its end shouldn’t be too much of a surprise. But until its main character, played by Akerman herself, blows up a room at its end, the short is set in a remarkably similar-looking kitchen to Jeanne’s and she is tasked with making herself dinner. Without Jeanne’s need for rituals, the main character finds even this small task to be too much for her and gradually demolishes the kitchen. This fun can’t last, though, and she decides to clean up her mess…but she also can’t change her personality, and soon she’s back to trashing the joint again before setting a fire and putting her head on a gas stove. Akerman described Saute ma ville as “the mirror image of Jeanne Dielman” in which this person who doesn’t need rules to govern her own life blows its rituals to bits. But because of its end, Saute ma ville, is not a description of a positive way to live life, rather than Jeanne’s existentially loathsome one. It in fact ends just as badly, with self-destruction just as inherent in completely abiding by these rules as it is in trying to destroy them. Akerman also looks at the film as “the next generation,” where the character in Saute ma ville refuses to live the way her predecessors did and thus throws out all of these rules. It’s easy to see a parallel between the hard-nosed ’50s in America and the ’60s’ response to this in these films, though that’s probably reading a bit too far. A bit more derivative than her later works, Saute ma ville was largely inspired by Jean-Luc Godard’s Pierret le fou and didn’t yet have the formalist bent of her later works, which mostly is to say that it doesn’t look a whole lot like the rest of her films. It also doesn’t look homemade, though, and while it doesn’t have the kind of time put into composition that the rest of her works did, its way of aligning the audience with the protagonist against the kitchen through claustrophobic framing manages to make the short fairly effective nonetheless. The experiments with asynchronous sound, mostly made up of a weird sing-song thing, are typically sophomoric for short avant-garde films from the era, but isn’t too annoying. Though calling Jeanne Dielman a remake of Saute ma ville as Rosenbaum does is quite an exaggeration, the two films do work beautifully together to comprise a fuller view of day-to-day work in general and the kitchens women can be forced into in particular.–Paste Staff

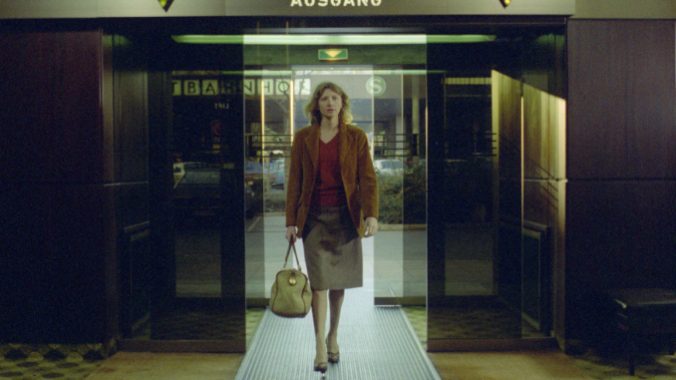

L’enfant aimé ou Je joue à être une femme mariée

Year: 1971

Director: Chantal Akerman

Stars: Chantal Akerman, Claire Wauthion

Runtime: 32 minutes

Chantal Akerman’s first short, Saute ma ville, was an explosive enough take on female domesticity to earn actual funding for her second: L’enfant aimé ou Je joue à être une femme mariée. Akerman sits around a French villa, listening to a young mother (Claire Wauthion) talk about her sex life, her evaluation of her own body, and other day-to-day topics while doing day-to-day things. Children and childishness is the thematic backbone of a film flirting with what will become Akerman’s quiet, dedicated formalism. “I Play at Being a Married Woman” is as revealing a title as the images within. Wauthion waxes hesitantly about her boyfriend, whom she feels motherly to both around the house and (perhaps unsurprisingly) in bed. Her child sings and counts and recounts fairy tales, maybe a more honest reflection of Wauthion’s character than the chores she’s stuck doing. Akerman is a sounding board, as much an object to stand in front of as the mirror that makes up the short film’s most effective scene. In fact, Akerman may have agreed on this point; she later clipped out the section where Wauthion, nude, critiques her physical form in a long unbroken take and created The Mirror. A languid movie uninterested in things like setting or narrative, L’enfant aimé ou Je joue à être une femme mariée observes. Yet, placed in context with the future observations Akerman will make under more strict artistic conditions, her sophomore movie can feel like a limited proof of concept.—Jacob Oller

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-