The Troubling Gender Politics and Cultural Appropriation of Author: The JT LeRoy Story

You hear a lot of aphoristic-sounding one-liners in Author: The JT LeRoy Story. We’re given a title card bearing a Fellini quote: “A created thing is never invented and it is never true: It is always and ever itself.” We’re offered excuses wrapped up in intellectual acrobatics: “A metaphor is different than a hoax.” We’re even presented with book titles that double up as hedged explanations: “The Heart is Deceitful Above All Things.” These are all thrown at the audience as ways to preempt our criticisms, or to sidestep them altogether. What seem like playful postmodern evasive maneuvers about the “author” in question are more troubling once you realize they function more forcefully as Hail Marys that seek to obscure the troubling gender politics at the heart of “JT Leroy.”

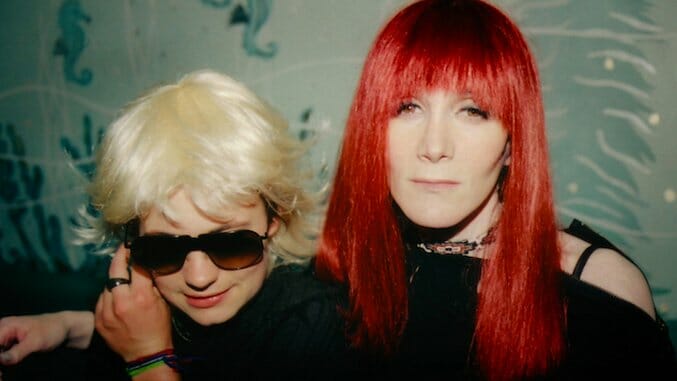

You see, JT LeRoy, author of the 1999 cult favorite novel Sarah, and friend of the likes of Winona Ryder, Courtney Love and Gus Van Sant, was unmasked as a fiction in 2006. The person many had been introduced to as Jeremiah Terminator (aka “JT”) was a young woman by the name of Savannah Knoop, the sister-in-law of Laura Albert, a Brooklyn-born, San Francisco-dwelling writer. Albert, who had often presented herself as LeRoy’s roommate-cum-manager Emily Frasier, also known as “Speedie,” was the person who had written the books that made LeRoy a sensation in the early aughts.

At the heart of the “JT LeRoy Story” is a tricky proposition about the fluidity of gender identity that remains the thorniest aspect of the whole thing. In a New York Magazine article that initially cast doubt on the veracity of LeRoy’s existence, Bay Area writer Stephen Beachy posited that since we “can never know for sure who’s on the other end of a screen name or a phone line, and given that these were LeRoy’s two chosen media, the possibilities of his identity seemed endless.” Of course, even that gendered reference feels ill-advised. After all, gender fluidity wasn’t only embedded into LeRoy’s own fiction—Sarah, promoted as a fictionalized version of LeRoy’s life, centered on a young boy who becomes a cross-dressing truck stop hustler—but was enacted in the bodies of the two women who made up his public persona: Laura, his voice, and Savannah, his face.

Any clear distinctions between male and female prove increasingly dubious when one begins to parse out the layers upon which LeRoy’s identity rested, especially once they’re blended through the sexual ambiguity that LeRoy nurtured: “When I wrote Sarah, I was male-identified,” LeRoy told the Village Voice back in 2001, “and now I’m not. I don’t know what I am.” In Jeff Feuerzeig’s film we see a photograph of actor Michael Pitt kissing Savannah-as-JT. We’re reminded he’s straight and felt he was experimenting. When Albert speaks of her encounters with Smashing Pumpkins frontman Billy Corgan, one of the few celebrity fans who knew the truth behind the LeRoy ruse, she admits that LeRoy spoke of his attraction to Corgan. She even talked to Corgan in person as LeRoy, whom the musician described as “part-man, part-wannabe woman, all androgyne” (and “as real as you, or I”) in the new foreword to Sarah. In her book Girl Boy Girl: How I Became JT LeRoy, Savannah admits she told Asia Argento, the Italian actress who would go on to write and direct an adaptation of LeRoy’s second book, that she’d taken hormones and had undergone gender reassignment surgery. “Wow, they make really good pussies these days,” Argento later boasted to the crowd at the New York premiere of The Heart Is Deceitful Above All Things. By the time the New York Times confirmed Beachy’s suspicions in a 2006 article, Savannah had reframed the entire adventure in Warholian terms: “I started out being JT to help [her half-brother] Geoff and Laura get their music and writing out there,” she told Vanity Fair. “But eventually it evolved into this exploration of gender, and it gave me permission to play with my identity.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-