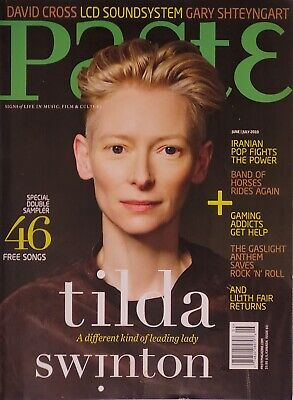

Tilda Swinton: The Love Factory

Photo by Michael Lavine

It’s 1988. Tilda Swinton is in a wedding dress, and her bridesmaids are all men. Big scruffy men with bouffant wigs and long flowing white gowns of their own. Glockenspiels and organs rub nightmarishly against industrial noise, but she looks radiant in the black-and-white glimpses the Super 8 camera snatches, even as the countryside burns around her—even as she takes pruning shears to the bridal fabric, tearing strips free and chewing them like gum. This is the final scene of Derek Jarman’s nightmarish film, The Last of England, and the young Swinton lends her beauty to a vision of the otherwise grotesque—firing squads in ski masks, refugees among the ruins, heroin addicts in underground lairs, and flames, always flames.

This experimental film was Swinton’s second with the boundary-pushing director, a collaboration that began with her screen debut, Caravaggio, and ended seven pictures later in 1993 with Wittgenstein, just a year before Jarman’s AIDS-related death. The association would indelibly mark the actress’ approach to filmmaking, whether carrying on a love affair with Brad Pitt’s title character in The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, playing the White Witch in Disney’s $180 million adaptation of The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe or, most recently, starring as a Russian immigrant in the much-lower budget Italian film I Am Love.

Her avant-garde beginnings made her a different kind of leading lady—one who cares less about the size of the project than the passion of those involved; one who’s chosen the remoteness of the Scottish Highlands over the tactical advantages of the Hollywood Hills; one who sees herself as a co-conspirator with eager young filmmakers; one who never really left the sway of her radical mentor.

“We used to be referred to as ‘the art house,’” Swinton narrates in the Jarman documentary Derek. “How it used to irk us then. How disparaging it sounded. How sickly and high-falutin’, how pious—and extracurricular. For ‘arthouse superstar,’ read ‘jumbo shrimp.’ Yet then as now, the myth prevailed that there was only one mainstream. We were only too happy to know that our audience existed and to hoe the row in peace. Nobody here [in Britain] paid that much attention to us then, that’s true. No one ever thought we would make them any money, I suppose. What grace that constituted—not to be identified as national product.”

Café Terigo is an oasis in the maelstrom that is Sundance. Sitting halfway up Park City’s Main Street, the two-story restaurant offers quiet Italian chamber music that might have served as the score of I Am Love, set in end-of-the-20th-Century Milan. She’s just finished introducing the movie’s second screening, her final official duty at the festival. Her normally flame-red hair is more simmering blonde today, cropped close on the sides. But the green eyes, pale complexion and sharp features that gave the Ice Queen her unquestionable authority are instantly recognizable to anyone who walks past. Draped in a purple shawl, she carries herself with the noble elegance of someone who can trace the family plot back to 9th-Century Scotland. She’s warm and engaging, but intimidating enough that I hesitate when attempting to repeat the word “milieu.”

She wasn’t cast in the role of Emma, the film’s quiet protagonist, because she was a perfect fit—she didn’t even speak Italian. Instead, the movie was created to fit her, to scratch her most recent itches. At age 49, the actress has never directed, but this is just the latest in a long line of films she’s helped create from inception—in this case, with director Luca Guadagnino.

Swinton’s acting career began with a season in the Royal Shakespeare Company “that most mainstream and traditional institution” but she was immediately attracted to the fringes, taking on gender-bending theatrical roles, like Mozart in Alexandr Pushkin’s Mozart and Salieri and as a woman impersonating her husband in Screenplay: Man to Man: Another Night of Rubbish on the Telly. By the time she met Jarman, acting had become just another item on a list of things she’d decided wasn’t for her. But working on Caravaggio, she learned that a performer could also be a filmmaker, that a director with a vision could invite collaboration and allow his cast and crew to flourish.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-