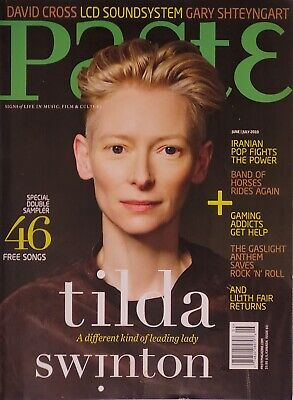

Tilda Swinton: The Love Factory

Photo by Michael Lavine

It was also where the idea for I Am Love began to take shape. Part of the discussion is about the revolution of love—the idea that love isn’t really about coming together as a unit, but two lonely souls keeping each other company.

“There’s a romantic notion that you can deny your solitariness when you come together and you’re one,” says Swinton. “You stop doing the things that you used to do before you got together and you’re just one—you do everything together, and you’re never going to be lonely again. Which I think is a great waste of human existence. I think being lonely and solitary is a great resource and to be enjoyed. And if anything, love is going to push you further into that.

“Out of that we decided to make a film about someone for whom the revolution of love really does break everything. We knew that we wanted to make a story around a character I would play. So we knew she would be a woman. Slowly we worked out that we wanted her to be an alien of some sort. So given that I’m not Italian and that I would be an alien anyway, we decided to place it in an Italian high capitalistic situation where denial is really the rule of law and place her in the center of that milieu, so that when love strikes, the honesty of it explodes the situation that she’s been in.”

It didn’t matter to Swinton or Guardagnino that she didn’t speak Italian, or that she would be called upon to do so with a Russian accent. They wanted to redeem the idea of melodrama, wondering why it had fallen so out of vogue. They went to Russian novels for inspiration, and to the masters of cinema: Alfred Hitchcock, Douglas Sirk, Luchino Visconti. And they went to Milan.

“We started thinking about this bourgeouis situation, this grid, this very circumscribed world,” Swinton says. “It’s not the feudal aristocracy of Visconti; it’s something much more modern, much less humanistic. It’s got a lot to be extremely discreet about. These people made their enormous wealth during the fascistic era. And if you’re going to make a film about that milieu in Italy, you know you have to make it in Milan. You walk down what you think is a perfectly normal business street, and if go through a courtyard, you come to a nearly-palazzo, hidden, very discreetly hidden. It’s a very particular place and people live in a very particular way there. So you think of someone who comes from a very circumscribed situation. The film is set 10 years ago, so if you backdate it, she comes from Soviet Russia—from that situation into an even more circumscribed situation. She’s like an avatar. She has to learn a new language, a new way of walking, a new way of talking, a whole set of behaviors.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-