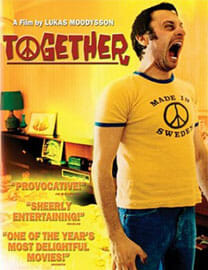

Together

If Bergman was the mid-century Scandinavian voice of conscience—creating dark, powerful films about the human experience in a world where God seems absent—Lukas Moodysson is his contemporary equivalent (though Moodysson directs with a somewhat lighter touch, focusing more on characters and stories than existential angst). Moodysson’s most accessible film—and a good place to start in understanding the current wave of Scandinavian cinema—is Together (now available on DVD in the US). Set in Stockholm in 1975, it focuses on a ’70s collective of radical socialists and the difficulties of communal life.

Goran and Lena have an open relationship, though Lena is much more interested in sleeping around than Goran. Erik is an irritable and dogmatic young man who’s broken all ties with his family and thinks others should follow his steps. Lasse and his wife Anna have divorced (Anna realized in therapy that she was a lesbian) but both still live in the house with their eight-year-old son, Tet. Yes, they named him after the famous Vietcong offensive. It’s that sort of house.

Into this wonderfully strange collective comes Goran’s sister, Elisabeth, and her two children—13-year-old Eva and 10-year-old Stefan—who are fleeing her abusive husband, Rolf. Though they have no socio-political leanings, they also have nowhere to go; so they take up residence in a place where washing dishes is considered bourgeois but one woman refuses to give up her room after she’s painted it the colors she wanted.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-