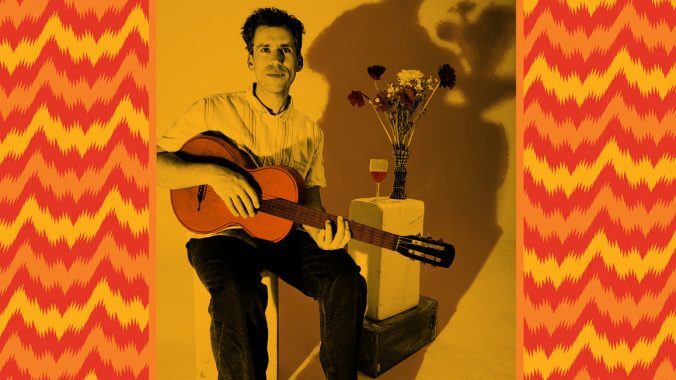

A. Savage’s Several Songs About Fire Roars and Dies Like a Flame

The Parquet Courts frontman’s sophomore solo album is sprawling and beautiful and, at times, saccharine and self-satisfied

The world is ablaze, and we’ve got to save what we can, however we can. At least, so pronounces A. Savage on his sophomore solo album, Several Songs About Fire. After churning out a slew of cheeky, radio-friendly coming-of-age hits—and some arguably-underrated musical investigation of the human condition—as the frontman of indie-punk outlet Parquet Court, Savage has set out on a more openly philosophic venture under his own name. First came 2017’s Thawing Dawn, a sweet, isolated portrait of a burgeoning folkster. Now, on his second LP, Savage is turning to the darker side of his psyche in a grand swing at melancholy. If it is anything, Several Songs About Fire is meticulously planned out: A brooding, flippant, precocious album that, in its best moments, roars to life in flickers of swelling guitars, burning harmonics and ingenious witticisms. At times, though, the album’s kindling fails to keep it alight, and it fades low under the weight of its own erudition.

Savage made Several Songs About Fire across the pond in Bristol, supported by singer/composer Jack Cooper and Welsh firebrand Cate Le Bon, who recently lent her production skills to Wilco’s phonetically-intricate Cousin. Savage’s topics sprawl from meditations on family and friends to indictments on modern society and nostalgia for a dangerous, masculinized Old West. He hops from genre to genre with swift deftness, signaling a familiarity with musical stylings from ‘90s Britrock on the brash, lively “Elvis in the Army” to acoustic ‘60’s folk on the softly contemplative “Hurtin’ or Healed.” His lyrics are colorful and heady, hinting at the sort of lone-wolf singer-songwriter persona Savage is working toward.

Indeed, if the album has a throughline, it’s that sighing “thinking man” trope perfected by the likes of Bill Callahan and Father John Misty—a half-serious, half-sardonic musical rendition of Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog. You can picture Savage himself on that much-mythologized promontory, musing about late-stage capitalism and the beautiful women he’s wronged—one of which, I feel compelled to add, he mentions in reference to a “menstrual lava goddess” just three songs in. Other collegiate, acid-trippy highlights include a tongue-in-cheek (I hope) self-comparison to Joyce and invocations to Proserpina—that’s right, no plebeian Persephone’s here. It’s the sort of lyricism that suffers from its own self-seriousness, flailing in an obnoxiously thesaurusized wasteland. This isn’t to say that Savage’s album is devoid of stunningly prosaic lyrics; take apologetic “you always belong to yourself, even when you’re not you / Every time I try escaping I lose” on “Mountain Time” or the “civilize me from a wilderness of constant mercy” refrain in “Thanksgiving Prayer.” There’s no doubt that Savage has the ability to tap into real musical profundity, the kind you can’t fake or half-ass.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-