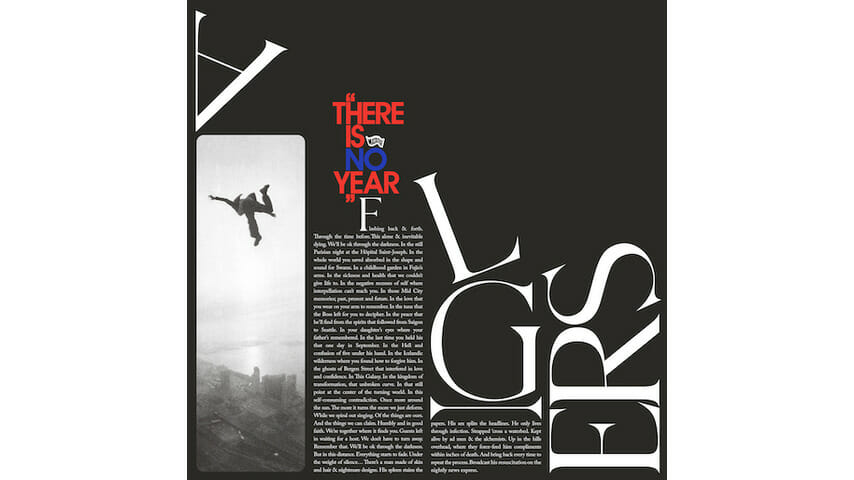

Algiers Sound Defeated on There Is No Year

The Atlanta quartet lose some of their revolutionary energy on their synth-heavy third record

With every day in 2020 so far somehow politically worse than the last, it’s easy to lose faith that a revolution—or even the smallest positive change—might actually happen in America. The Democrats are poised to nominate a centrist candidate over the race’s furthest-left candidate, Bernie Sanders, who actually has the numbers behind him to suggest that he might actually be able to win this year’s presidential election. “I’m into him as much as I can be behind any political figure,” Franklin James Fisher, lead singer of the anti-capitalist, anti-fascist band Algiers, said of the candidate in 2016.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-