The 14 Best Anaïs Mitchell Songs

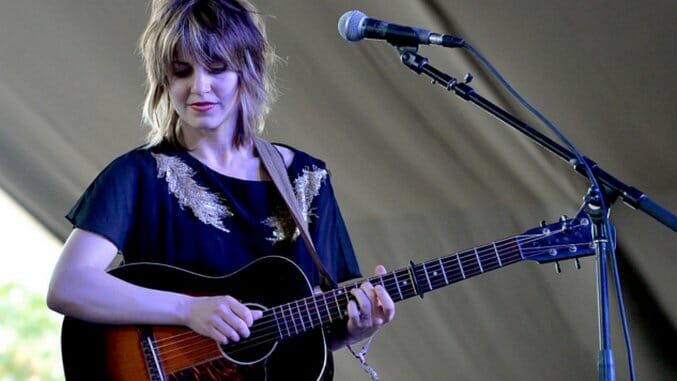

Photos by Getty's Matt Cowan

Anaïs Mitchell has been called “the queen of modern folk music.” Her poetic lyrics have been likened to those of Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen. She wrote an off-Broadway musical about which Lin-Manuel Miranda recently raved. And yet, despite such accolades, she has never quite gotten the attention her music deserves.

Mitchell writes many of her songs about history, politics, folklore, and—self-reflectively—how music can explore those topics to document and shape the world. She is both a wielder of and commentator on music’s potential as a change agent, and this has been true from the title track of her debut album, The Song They Sang… When Rome Fell, to her most recent artistic work, the musical Hadestown, a retelling of the Orpheus myth in Depression-era America. In an interview with The New York Times about the show, she said, “Whether or not you can change the world with a song, […] you still have to try.”

Earnest, observant, and philosophical, Mitchell brings poignancy to the ordinary and meaning to adversity. Looking back at her extraordinary, if too often overlooked career, here are 14 of the best songs by Anaïs Mitchell (excluding collaborative projects such as Hadestown).

14. “Come September”

Fading love and autumnal decay—it’s a hackneyed pairing, but Mitchell makes it feel fresh. She jaunts through a progression of exclusively minor chords (rare in folk music) to tell of an ended romance from a detached, seemingly wizened perspective. “Come September” is an older song that Mitchell rerecorded for her latest album xoa.

13. “Shenandoah”

A delicate duet of banjo and guitar evokes the southern countryside of an American legend in which a white settler falls in love with the daughter of Shenandoah, an Algonquian chief. Mitchell has a knack for beautiful melodies, one that she has refined by opting for simplicity over the sometimes-overdone vocal maneuverings of her early career. The gentle “Shenandoah” moves through one of the loveliest tunes she has ever written, made even more so by the harmonies in the “oh”s of the chorus. The archetypal free-spirited woman has been a muse since the dawn of fiction, but rarely is her story rendered as moving as it is here.

12. “Coming Down”

This track, in contrast to Mitchell’s catalog of detailed narratives, is unadorned and straightforward. “I never felt so high / I think I’m comin’ down,” Mitchell murmurs over a sparse piano accompaniment. Her voice is wistful and vulnerable as it descends in imitation of “coming down.” It is impossible to say what the purest expression of sadness sounds like, but this must come close to it.

11. “He Did”

Mitchell’s album Young Man in America was largely inspired by her father, nowhere more obviously than on “He Did,” where she tackles the complexity of his relationship with his own father. With the repetition of the appropriately ambiguous phrase, “How it feels / to be a child of his,” she avoids abridging the nature of their bond and instead invites us to imagine it. The track features emotive instrumental layers to sink into and Dylan-esque turns of phrase to contemplate: “Like a splinter in the wood / he couldn’t pull you from his heels.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-