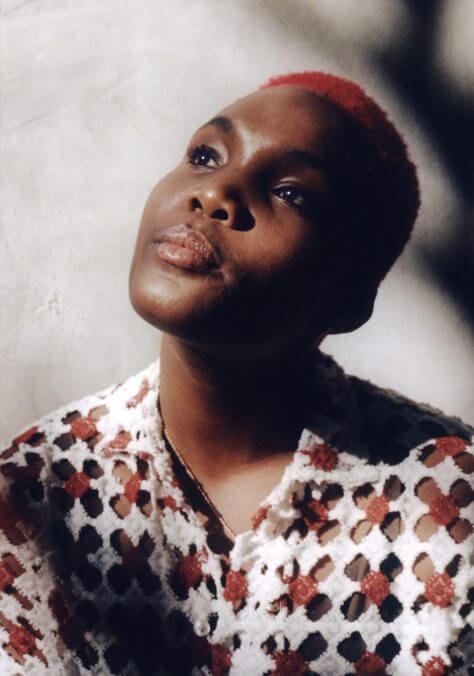

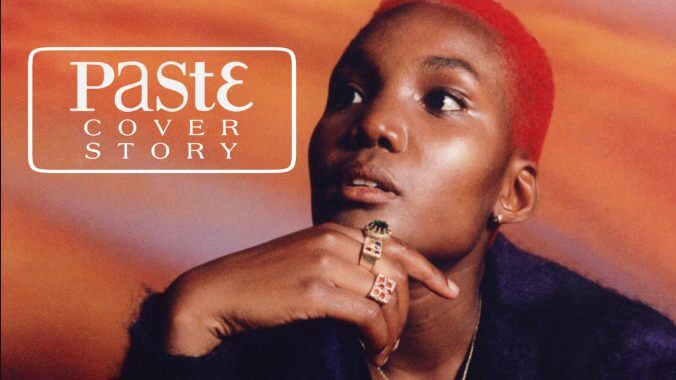

COVER STORY | Arlo Parks Embraces the Intimacy of Aliveness

The English singer/songwriter talks finding a temple in stillness, the literary language of hip-hop and her sophomore album My Soft Machine

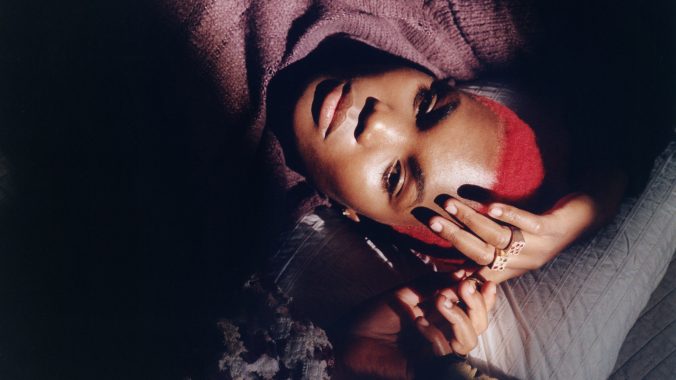

Photos by Alexandra Waespi & Vince Mayo M. Aung

I was—admittedly—not immediately hip to Arlo Parks’ brilliance. But don’t get it twisted, I was fully there when her debut LP Collapsed in Sunbeams came out in 2021. And, my goodness, what a treasure that project was to behold. Few debuts in the last decade—maybe even this century—have been so literary, soulful and paradisiacal. “Too Good” itself endures as a monumental, sultry soul tune that will outlive us all. In the confines of the music industry, Parks was born in a different millennium than most of her peers; yet, when she wrote “Super Sad Generation” at the age of 17 on the back of a napkin, something perfect was born in that moment. And ever since, she has—slowly, but rapturously—held court at the intersection of indie rock and R&B.

I am often reluctant to embrace my Generation Z identity. Being born in 1998, I cling to the Millennial cusp—which wasn’t made to include me in the first place—as much as possible, lamenting the rigorous “90s Baby” prophecy I worked so hard to fill. I played GoldenEye 007 on Nintendo 64; I worshiped American Idiot once upon a time; I filled up on hefty doses of Nickelodeon’s Golden Age. However, when I tap into Parks’ work, I become willing—and excited—to call myself a Zoomer and unhinge my identity from the jaws of those surfing across their 30s. How could you not be, when someone as gravitational as her is holed up at the frontlines?

The 12 chapters that comprise Collapsed in Sunbeams, from the title track to “Portra 400,” all combine to make one singular organism: a muscle of heartache, loved and worn-in characters and zeitgeist reference points. “Too Good” and “Black Dog” and “Eugene” are all earworms that have long wedged their ways onto our playlists forever; “Caroline” even made a cameo performance on the second season of Ted Lasso, only a handful of months after the album’s release in January 2021. As one of the first superstars to come out of a world forever-changed by COVID-19, Parks rekindled my own hope in finding a voice—not an answer—for what shape my body was meant to take once lockdowns subsided.

Parks’ eclectic, familiar range of taste can pull any listener in, but it’s her deft, uncanny songwriting prowess that keeps you hooked until the last breathing note. To find common ground through watching Twin Peaks and longing for our mothers is only one piece of the puzzle. It is when we watch the echoes of our hearts bend around the curtain call of a relationship—one that’s surrender came on the heels of a fear of taking queer intimacy into the public eye—that we are alive in the wake of Parks’ diaristic, communal grieving and passionate charm.

Collapsed in Sunbeams has endured because the songs are as timeless as they are deep-pocketed. Each time I return to its tracklist, I find a new moment to fall in love with and a new person to meet—and that’s the purest genesis of a piece of art that transcends eras. When Parks returned to us earlier this year to announce her sophomore album My Soft Machine, I remembered that—per the textbook creative cycle that recording artists must endure—the time had arrived for another entry in her catalog. Though I was still spending as much time with Collapsed in Sunbeams as I was the week it dropped two years ago, I can’t lie: I wanted to see where one of the most-brilliant musicians of my generation would go next; how she would begin to live up to the project that had made her a household name barely 700 days prior.

When I get on Zoom with Parks on a rainy weekday, she’s in full globetrotter mode—having just done a stint in Los Angeles before jetting off to New York and then back to London and then to Brazil all in a matter of days. The last two years have almost constantly flirted with a similar business for Parks, who—in the last 24 months—has toured with Clairo, Lorde, Harry Styles and Billie Eilish, been nominated for two Grammys and won the highly coveted Mercury Prize for Best Album. Collapsed in Sunbeams—which was at the center of it all—was a smash, but its release and widely beloved praise didn’t come without whirlwinds of excess and non-stop movement.

“‘Living in the dream’ and being inside my dream and reckoning with the reality of that and how confusing and incredible and turbulent that time was, for me, it really encouraged me to—at any moment I could—retreat into myself and throw myself back into books, into films, into reading scripts and going for walks,” Parks says. “I had to be really intentional with balancing, having time alone whilst being very much out in the world and having enough energy to give not just to the crowd, but also to myself.”

Parks has long coveted and protected a temple of stillness, allowing herself to be in one space with her thoughts, body and energy. This past Christmastime, after finishing My Soft Machine and cancelling shows amidst a case of burnout, she decamped to Mexico with some beloveds from her inner-circle and started writing again. She uses the word “intentional” more than once, emphasizing just how precious she has to be about her own downtime in the wake of a never-ending tour itinerary, a new album cycle and the dozens of other irons she has in her own fire. “It’s part of what makes me feel grounded, what makes me feel like myself: making little notes and annotating my books and spending time with my dog,” Parks says. “I was really intentional about protecting that time, especially going into this year.”

Most of My Soft Machine was made in Los Angeles, where Parks spent large chunks of her time lounging by the Pacific Ocean, taking to the beach with her friends, eating fruit and listening to Frank Ocean’s Blonde on a bluetooth speaker. While many of the stories on My Soft Machine find Parks returning to distinct memories in her own coming-of-age and reflecting and interacting with them in new ways broadened by young adulthood, she often replenishes her mid-album creative energy by taking to the privacy of her own getaways.

“A lot of it was just immersing myself in nature and feeling quite small,” she adds. “I feel like I need to remove myself from my context in order to feel truly still. Listening to a podcast and going on a very long drive up to the Angeles Crest Mountains and then sitting and looking at the city and reading my book, I find a lot of stillness in a mini, healthy escape.” Parks is often working on being a vulnerable voice for the people who don’t have one. In turn, My Soft Machine was a great source of healing for the 22-year-old as, for the first time in her career, she’s being that voice for herself. All of that stems from her own writing process, which has been a restorative exercise and haven for her. She even goes as far as calling it “the most-extreme form of meditation.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-