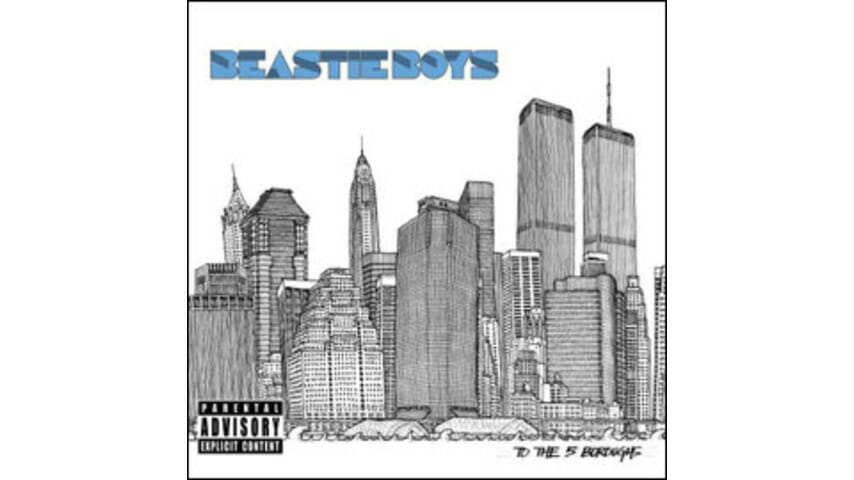

Beastie Boys – To The 5 Boroughs

Impossibly crowded skyline, dirty streets, high rent, yellow taxi fleets, miserable winter slush, celebrity mayor, Thanksgiving Day parade, Letterman, Wall Street. While most major metropolitan cities can claim at least a few of these characteristics, New York City has somehow transcended, become less metropolis and more localized cult religion (with attendant small-scale jingoistic tendencies). Where other cities’ ratty weeklies leave newsprint on your fingertips; NYC’s famous weekly—a pious, glossy little rag called The New Yorker—routinely fills mailboxes, confronting subscribers from Muncie to Munich with their pitiable outsider status. But only New York City—not Chicago, not L.A., not Atlanta—can boast the following title: cradle of hip-hop.

By the time the Beastie Boys (hailing from Manhattan’s Lower East Side) arrived on the scene in the early ’80s, initially as a hardcore-punk outfit, New York hip-hop pioneers like the Sugarhill Gang and Grand Master Flash had already lit the fuse of popular acclaim with their mega-hit singles “Rapper’s Delight” and “The Message,” respectively. The aesthetics of hip-hop, which crystallized in the late ’70s amid block parties in the projects of Harlem and the South Bronx, gave voice to a frustratingly invisible generation of African American youth growing up in the inner city.

Its practitioners had plenty to challenge in society (and often did, complementing the punk movement already underway), but many of hip-hop’s early jams were content to simply provide a cathartic, sweaty release through dance and funky-frivolous rhyming. Hip-hop would soon bring about a widespread awareness of ghetto life. It would only be a matter of time before the rest of the country finally took notice. This process accelerated significantly as hordes of suburban white teens began latching onto hip-hop’s sense of alienated discontent, putting the fear of Yaweh in politicians and fastidious parents alike.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-