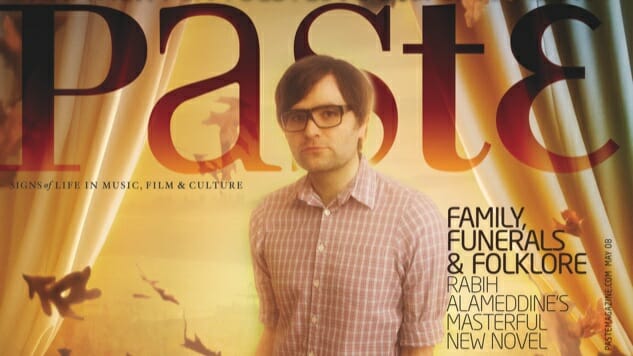

Ben Gibbard on the Meaning of Life, 10 Years Later

We sent the Death Cab for Cutie frontman to Big Sur to reflect

Cover photo by Jayme Thornton; styling by Brendan Cannon

Ten years ago, Death Cab for Cutie frontman Ben Gibbard retreated to the rustic California town of Big Sur to write songs for his band’s new record, Narrow Stairs, and to commune with the spirit of his idol Jack Kerouac, who’d visited Big Sur almost a half-century earlier. For the cover story of Paste issue #42, we sent Gibbard back to his cabin in the woods to meditate on life, art and solitude. Today, to mark the 10th anniversary of the release of Narrow Stairs, we’re revisiting that story here.

Part I

Why did I think I was going to come here and have this place change my life? I wanted it so badly, as I’m sure Kerouac did. I wanted to cleanse myself with this place. I’d spent years wondering what it looked like, wondering what it would be like to be here. And now here I am, sleeping in the same room Kerouac slept in. I’m walking the same path he walked when he came to the beach and wrote. Jack Kerouac sat here and wrote poems about the sound of the ocean. He sat right here.

There’s something ominous about venturing into this canyon. The first line of the first song I wrote here is, “I descended a dusty gravel ridge”—it’s like the whole album is a descent. Being here for two weeks was productive, but it was also very reflective in a not-so-comfortable way. I realized some things about myself that I don’t really like, and to come back here and be reminded of all that made me feel really anxious from the moment I first turned down the driveway. The epiphany never came. I’m just as confused now as I was when I got here six months ago. And when I returned to start thinking about this essay, I wasn’t sure that I wanted to be back.

I’d totally idealized what I’d be able to accomplish down here. I thought I needed to go somewhere to finish this record, figuring it wasn’t something I could do from the comfort of my own home, like the other 30 songs I wrote. I wanted isolation, which in a way is odd. It’s not like I have a drug problem, or I have a hard time concentrating, or I’m lazy. I idealized coming here for sentimental reasons.

I read On The Road in college. I was 18 or 19, and I had a particular quarter where I was taking biology, calculus and physics. Those were my three classes. It wasn’t a well-rounded schedule at all. It was hard, hard work, all the time-—hours and hours and hours of homework. My brain was just full of all these specific equations; there was no fun whatsoever. But I pulled On The Road off the shelf and found myself reading it between classes, and at that time in my life it was exactly what I craved, exactly what I needed to hear. I thought, “That’s the way, that’s the ideal life, that’s great. You get in a car and you drive and you see your friends and you end up in a city for a night and you go out drinking and you catch up and you share these really intense experiences. And then you’re on the road and you’re doing it again.” The romance of the road, particularly from Kerouac’s work, encapsulated how I wanted to live. I found a way to do it by being a musician, which is what I always wanted to be. The traveling and the being on tour and being away from home set a precedent for me where I thought, “Oh yeah, this is how it works.”

I read On The Road in college. I was 18 or 19, and I had a particular quarter where I was taking biology, calculus and physics. Those were my three classes. It wasn’t a well-rounded schedule at all. It was hard, hard work, all the time-—hours and hours and hours of homework. My brain was just full of all these specific equations; there was no fun whatsoever. But I pulled On The Road off the shelf and found myself reading it between classes, and at that time in my life it was exactly what I craved, exactly what I needed to hear. I thought, “That’s the way, that’s the ideal life, that’s great. You get in a car and you drive and you see your friends and you end up in a city for a night and you go out drinking and you catch up and you share these really intense experiences. And then you’re on the road and you’re doing it again.” The romance of the road, particularly from Kerouac’s work, encapsulated how I wanted to live. I found a way to do it by being a musician, which is what I always wanted to be. The traveling and the being on tour and being away from home set a precedent for me where I thought, “Oh yeah, this is how it works.”

But then in reading Big Sur, it’s the end of the road. You end up with a series of failed relationships and you end up being an alcoholic and in your late 30s, and not having any kind of real grip on the lives of the people around you. That’s the potential other end of the spectrum when you’re never tied to anybody or anything. I run the risk of losing touch with the people in my life that mean the most to me because I have made the decision to live like this.

If you tell certain people that you like Kerouac, they assume that’s all you read, like you don’t know anything else about literature. I recognize all the things that people dislike about the way he writes—his tone and the sentimentality of it all. But those books were there for me at a very important point in my life.

And moments in Big Sur are starting to become very analogous to my life, where I show up in a town and call up my friends, and I’m like, “Guys, we gotta go out. Let’s hang out, I haven’t seen you in forever.” And their response is “Yeah, well, our baby needs to be going to sleep and I can’t be out all hours of the night anymore. It’s time to move on in our lives into another phase; we can’t live in this perpetual adolescence forever.”

Because of my age and what I do for a living and the amount of time that I’ve spent away from my family and loved ones, I’m starting to relate more to the late-period Kerouac stuff in the way that I once related to the fun and excitement of the early material. There’s a darkness inside of me that I’m only now starting to come to grips with and accept. And it’s starting to scare me.

Part II

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-